Humor, A Characteristic of the Irish

A characteristic of the Irish that has been memorialized in books, poems, plays, lectures, ballad and song for centuries, is their ‘humor’.

“That there is such a thing as Irish wit, as well as Irish bulls, or blunders, and also Irish humour, will hardly be disputed by anyone who has traveled much in these Kingdoms, and who has given any attention to national peculiarities.”

The above is taken from ‘Irish diamonds; or, A theory of Irish wit and blunders’ written by John Smith and published in 1847, which was praised in newspapers of the times.

Following are extracts and transcriptions compiled by Teena from the cited resources.

Richard Stanihurst, (1547–1618,) an Anglo-Irish alchemist, historian, poet and translator, who was born in Dublin, described the Irish people in the following manner;

“The Irish are thus inclined; religious, frank, amorous, ireful, sufferable of infinite pains, vain-glorious, with many sorcerers, excellent horsemen, delighted with warring, great almes-givers and surpassing in hospitality. The lewder sort (both clerics and lay people alike) are sensual and loose in living. They are sharp-witted, lovers of learning, adventurous, kind-hearted and secret in displeasure.”

From the article ‘A Reflection on Saint Patrick and the Nature of Being Irish’ by Father John P. Cush https://bit.ly/2QJaq7Q

The Irish people enjoy a world-wide reputation for colloquial humour. It is theirs by the best of all rights, the right of having well-earned it.

The colloquial drollery of the Irish people has been the source from which many generations of the English-speaking peoples of the globe have drawn much wholesome and hearty laughter. What is the national characteristic of this humour of the Irish people? What is the element in it which excites us to laughter? It cannot, perhaps, be exactly and precisely defined.

Indeed, the attempts which have been made by several acute literary critics to define the nature and composition of humour generally, have been to little advantage. We hear a good story and enjoy it; but if we were asked what it was exactly in the story, that excited in us the feeling of pleasure, that stirred in us the emotion of surprise, that made us shout with laughter, we would often be at a loss to explain.

However, this much I may say as a generalization on the subject of Irish humour. Everything, no matter how sober, serious, or solemn, has its comic, or its ludicrous side, (if we could only see it) and it seems to me that the source of Irish humour lies in the extraordinary intuition of the people in discovering this, not always obvious, side of a situation.

(Irish life and Character 1898 by Michael McDonagh https://bit.ly/32EEmrC)

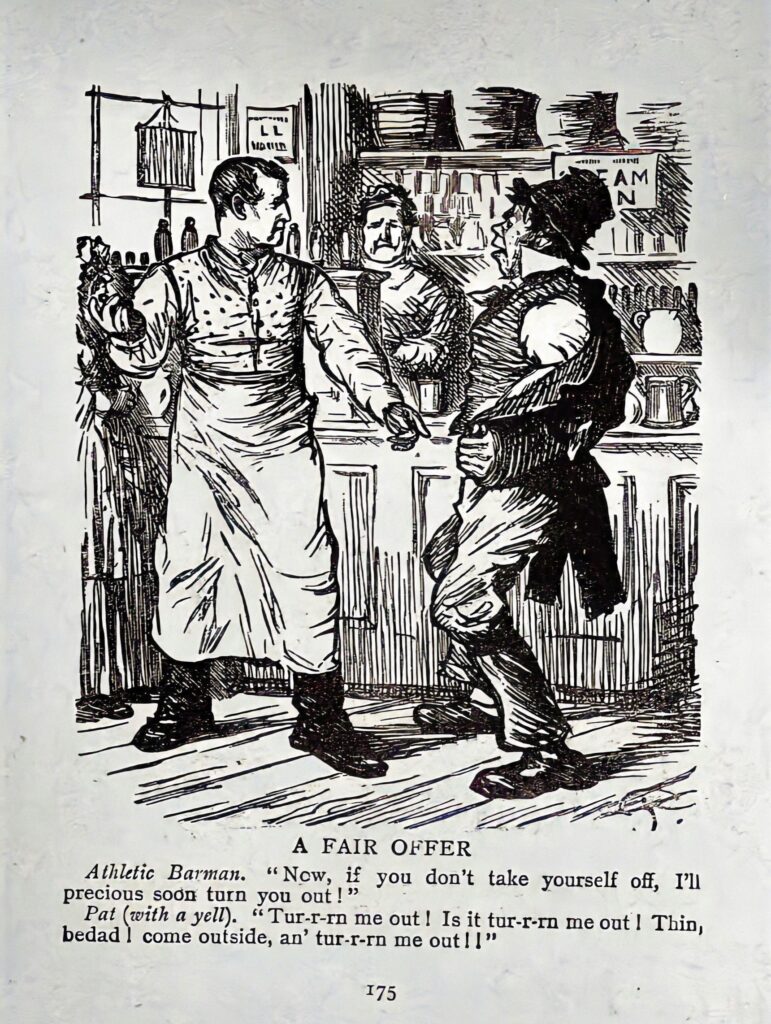

Athletic Barman “Now, if you don’t take yourself off, I’ll precious soon turn you out”.

Pat, with a yell, “Tur-r-rn me out!” Is it Tur-r-rn me out! Thin bedad! Come outside and tur-r-rn me out!”

Some men have the humour of holding you by the button when you meet them and they keep you in custody till they can perpetrate something, which, however stupid, induces you to laugh and then, they march off crowingly. But of all people I have ever been amongst, the Irish have the particular vein of humour, which I deem best worthy of notice, because it is the most lively, innocent and mirth provoking.

To the honour of the Irish be it said, their humour is very pleasant, because it is of a mirthful kind. It exhibits itself to a stranger in all cases of inquiry, or of casual observation, through a determination, on the part of an Irishman or Irishwoman, to say something promptly to the point, or about the point, or even off the point; it is of little consequence which. On asking questions in Ireland, we never meet with a yawning “don’t know”, “can’t tell”, “never noticed”. An answer we are sure to have, whether such as was expected, or not, and in many cases it will be piquant and memorable.

A fashionable Irish gentleman driving a good deal about Cheltenham was observed to have the not very graceful habit of lolling his tongue out, as he went along. Curran, who was there, was asked what he thought could be his countryman’s motive for giving the instrument of eloquence such an airing. “Oh”, said he, “he’s trying to catch the English accent.”

(Irish Diamonds: Or, A Theory of Irish Wit and Blunders. by John Smith 1847 https://bit.ly/3bfOCdE)

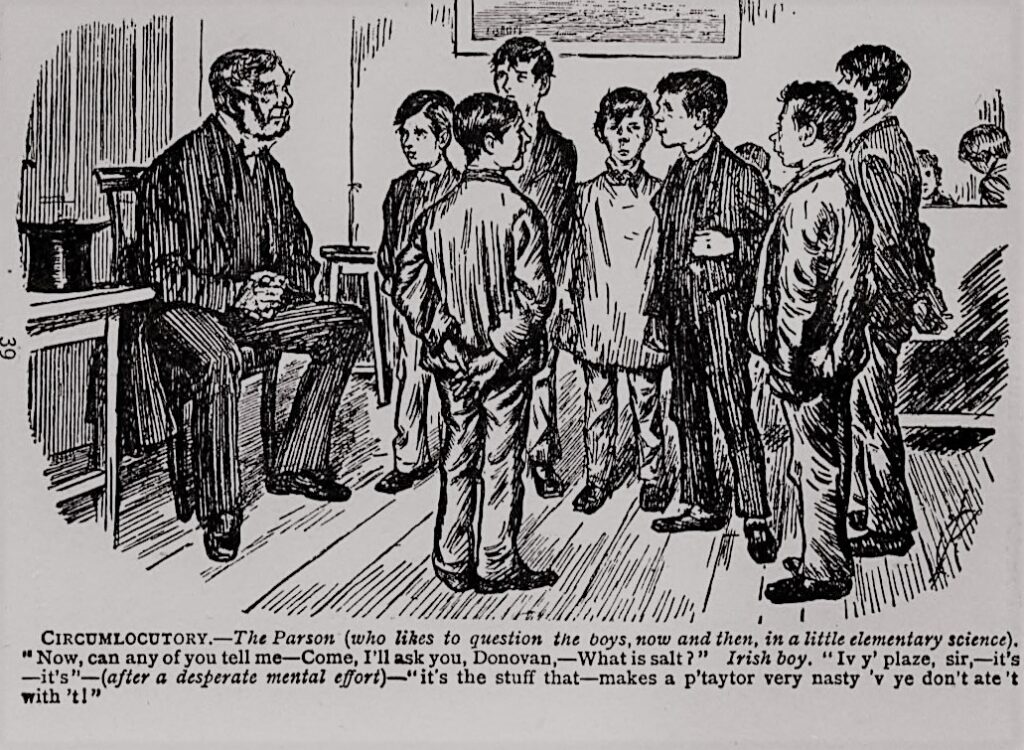

Irish boy “Iv y’ plaze sir, – it’s – it’s – (after a desperate mental effort) – it’s the stuff that – makes a p’taytor very nasty ‘v ye don’t ate’t with ‘t”

29 Jun. 1822

The lower orders of Irish are so prone to pleasantry, that even the deepest distress cannot quell the prevailing humour. A miserable beggar in a street of London the other day was asked by a gentleman relieving him, why he did not stay at home, since he could not be worse off anywhere, than where he now was.

“Shall I tell your Honour truly, why we came over?”, was the reply. “If you please, then by my soul, we came over to look after the absentees.” (Belfast Commercial Chronicle)

21 Jun. 1839

Not long ago we expressed our sympathy for an old Irish woman – old, and very poor – who, in addition to her other misfortunes, had lately lost her teeth, “Time for me to lose em” she replied, “when I’ve nothing for ’em to do.”

This is “Irish Humour” – a definition in an anecdote. It arrives most rapidly at a conclusion by the pleasantest road – it accomplishes a purpose without a useless expenditure of words; it is epigrammatic and yet comprehensive; it is ambiguous and yet easily understood; it is a picture, as well as a speech; it tickles the ear; animates the fancy and indirectly flatters an auditor by enabling him to compliment his own quickness of apprehension, in taking in the full meaning of the words. Like everything else that is Irish, it is peculiar; it is not a pun, or a joke, or a quiz; it is unstudied; it comes unsearched for and uncalled for; it has an air of simplicity and yet simplicity is not its character; it belongs more to the mind, than to the tongue, and more to the heart, than to either. To relish Irish humour, it is almost necessary to see it acted, as well as to hear spoken then, indeed, you have it in all its rich and racy perfection; the words of the Irish speaker are always illustrated, explained and commented upon, by his looks; his merry eye winks without effort; there is both shyness and slyness in his leer, the muscles of the mouth agitate that expressive feature into almost a smile; his very frame partakes of the drollery of his countenance; he lounges against the door-post of his cabin, one foot rests upon the instep of another; there is a mingling of entire ease and more than half impudence, in the loose tye of his neckerchief and sit of his “caw-been” (?) and when he has uttered a humorous sentence, the indescribable twist of the shoulders (the Irish substitute for the Englishman’s moderate – and the Frenchman’s immoderate, shrug), is once irresistible and inimitable.

Imagine for a moment a rosy cheeked Munster man, paving rather leisurely the highway in Cheapside, and quite unconscious of the English dignity of a shopkeeper, blocking up a tradesman’s door with a heap of stones. “Take those stones away,” quoth the tradesman in a fluster. “Is it the stones?” asks the Irishman; “is it the stones? Why, thin, where would you have me take ’em to?” “Take them to H -” replies the very angry citizen. I’ll tak ’em to Heaven, your honour, they’ll be more out of your way there”, was Paddy’s reply. Now fancy his under glance of self satisfaction – the fellows overt civility and covert nature, his silent chuckle, intimated only by the least twirl of his mobile mouth, the whole finished by the never neglected shoulder twist, as he stoops to resume his labour and you have at once a picture of veritable Irish humour.

It is indeed, as we have said, inimitable, as well as irresistible – the cleverest of our mimics, the most successful of our actors, the most skillful of our raconteurs have failed to convey of it, a just, and accurate notion. Mathews, although he gave poor Paddy many a generous hit, and brought a large store of pleasant character and anecdote from the “Land of the West,” never carried the auditor, or rather, the observer, to the very sod itself; the brogue he learned to perfection, the wit he borrowed extensively and put it out to profitable interest; but he never succeeded in catching from an Irishman, the look of humour that, as we have stated, always illustrates and explains the humour spoken. Power, beyond all question the truest actor of our time, does the thing far better; his laugh is the thing itself, but the shoulder twist he has not acquired; it is, perhaps, too slight and quiet for the stage and Power, although he cannot, but have observed it, has not, we believe, transferred the delicate touch of the original to any of his copies.

But examples of Irish humour, though they may not be absolutely perfect, are rife enough; they form the staple of our joke books and the life and spirit of Irish novels. Hundreds have been recorded, and hundreds remain unrepeated; an Irishman never blunders from stupidity, he blunders because his head has more than it can carry, he never lacks ideas, but he strings them oddly together, arriving at his conclusion, by a shorter way than an Englishman would have dreamed of taking. He relishes his potatoes with a jest, and flutters his rags with merry laughter. Even Irish gentlemen, at times, commit themselves in the blundering style, though constant intercourse with England has somewhat flattened their wit, if it has added to their wisdom.

Not long since, we received a note of sympathy that we should have chosen a very unfortunate period for visiting the Irish metropolis, “when there’s nothing to see, and nobody to show it.” And a short time afterwards one of the riders of a steeple-chase, finding his horse boggle at a ditch, (Anglice‘, hedge), thus addressed his steed, “Leap it now, and I’ll give you a pound note.” Upon being subsequently questioned to the effect of the promised bribe, he added, “And she did lep it, and fell on her face and hands.”

Of a kin to this, is the story of an Irish gentleman, who being in Paris, and not understanding French, drove to the hotel, at which, having been there before, he knew an English waiter attended. Having summoned the garcon’ the following dialogue took place;

“Waiter, bring me some gravy soup.”

“Monsieur?”

“Some – gravy – soup. Will you bring me the gravy soup? Don’t stand bowing and jabbering there, sure that’s what I’m wanting, and not your civility.”

“Monsieur, je ne com -“

“Tunder and turf, man alive! if ye don’t understand me, can’t ye send me the man I saw when I was here last?”

We will only give one more anecdote, to illustrate the ready wittedness of Paddy, whose humour did not forsake him even in the presence of his priest, or beneath the shadow of the confessional. Darby Kelly went to confession and having detailed his several sins of omission and commission, to which various small penalties were attached, at last came, with a groan, to the awful fact that he had stolen his neighbour, Kitty Mahony’s pig; a crime so heinous in the sight of Father Tobin, that his reverence could by no manner of means give him absolution for the same. Darby begged and prayed and promised, but to no effect; no penance could make atonement; no repentance could produce effect; nothing in short, would do but restitution – that is to say, to give back her own to Kitty Mahony. But a difficulty arose, inasmuch as Darby and Darby’s childre’ had eaten the pig. Upon which the priest waxed wroth and threatened the rogue with evil here and a terrible destiny hereafter. “And now here me, ye vagabond cheat,” said he, “when ye go up to stand yer trial and finding yerself among the goats, (for sheep ye are not), to get yer sentence, there’ll be two witnesses against ye, there’ll be Kitty Mahony that ye robb’d, and the pig that ye ate and what will you do then, ye vagabond?”

Och, plaze yer riverence, and is it true what ye say, that Kitty Mahony herself will be there?”

“She will.”

“And the pig I ate; will the pig be to the fore?”

“He will.”

“Oh, thin, plaze yer riverence, if Kitty will be there, and the pig will be there, what’ll hinder me from saying, “Kitty Mahony, bad luck to yer soul there’s yer pig; sure won’t that be restitution?” (London and Westminster Review)

21 Oct. 1875

A mournful cortege of a funeral, while on its way through a town, stopped at a public-house for refreshments. The incident was so unusual, that a policeman, for the sake of gaining information about such a strange party, asked the man in charge of the mystic hearse,”Who is dead?”

With a leer and a shrug the reply was given, “The man in the coffin,” and the policeman retired. As a specimen of Ulster wit, it would be difficult to surpass the answer. (Ballymoney Free Press)

27 Feb. 1886

An Irishman entered a hatter’s and approaching the counter, said he wished to purchase a hat. “What size, sir?” asked the assistant. “Begorra, I don’t know,” said the Hibernian, scratching his head, but I take noines in boots”

An Irish soldier was asked if he enjoyed the hospitality of the Southern people during the rebellion and replied, “Oh, yes, too much. I was in the hospital narely the whole the toime I was there.”

An honest Hibernian, trundling along a handcart containing all his moveables, was accosted by a friend with, “Well, Patrick, you are moving again, I see.”Faith, I am,” he replied. The times are so hard, it’s a dale chaper hiring handcarts than paying rints!”

“Hi! where did you get them trousers?” asked an Irishman of a man who happened to be passing by with a pair of remarkably short trousers on. “I got them where they grew,” was the indignant reply.

Then, be my conscience,” said Paddy, “you’ve pulled them a year too soon.”

An Irishman having signed the pledge, was charged soon afterwards with being drunk. ” ‘Twas me absent-mindedness” said Pat, “an’ a habit I have of talking wid meself. I said to meself, sez I, “Pat, come in, and have a dhrink.” “No, sor,” sez I, “I’ve sworn off.” “Then I’ll dhrink alone,” sez I to meself. “An’ I’ll wait for ye outside,” sez I. An’ whin meself cum out, faith an’ he was dhrunk.”

An Irishman was observed, day after day and hour after hour, crossing the river Shannon on the ferry boat, apparently without any motive. The neighbours began to doubt the man’s sanity, so one of them was deputed to interview the suspected Mick Flanigan. “Arrah, Mick, and how is it that ye kape crassin’ and raycrassin’ the river fifty toimes a day?””Don’t yea know, Phaylin, that I’m goin’ to immigrate to Ameriky?””Phwat of that, Mick?””Phwat of that? Can’t yez see that I’m afther practoisin’ the say sickness?”South London Press

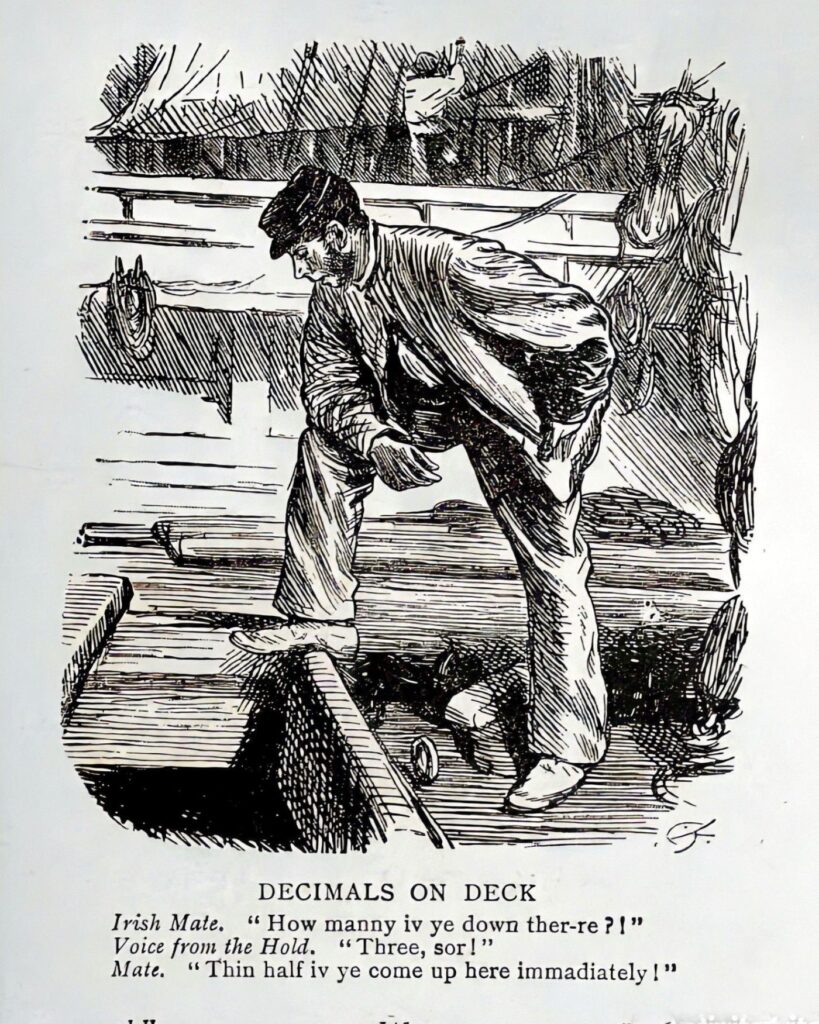

Irish mate “How many iv’ ye down ther-re?”

Voice from the hold “Three, sor”.

Mate, “Thin half iv ye come up here immediately”

26 Nov. 1892 Funny Irish Blunders

The native of the Green Isle who said, “It’s a great comfort to be left alone when your sweetheart is with you,” and the Irish auctioneer who, while praising some goods he was offering for sale, exclaimed, “These are just the things I should like to buy for my wife if she were a widow,” made very witty bulls. Equally good, but even more complicated, was that perpetrated

by the exile in America, who pathetically expressed himself thus ; “Sure an’ if I live till I die, an’ God knows whether I will or not, I’ll visit ould Oireland afore I lave Philadelfy.” A funnier blunder still, was that made by a new chum Hibernian, who was a passenger by the Southern Express the other night. He alighted, with other thirsty souls, at Mittagong, but lingered at the bar over his favourite nectar, longer than he should and only regained the platform in time to see the tail-lights of the train by which he intended to have journeyed, receding from his view. For a moment he was dumb with astonishment and then collecting all the energy and presence of mind he was capable of exerting, he cried, “Hould on there, ye blatherin’ engine; faix, there’s a man on board of ye that’s left behind! ”

These stories have all the true Irish ring about them and call up memories of the Irishman who complained to his physician that he “gave him so many drugs he was sick a long time after he got well.” (The bulletin. Vol. 12 No. 667)

28 Mar. 1903

“Irish humour” seems to be as eternally green as the Irish shore, says “The Macon News.” Nothing in the way of misfortune or trouble can wholly destroy it. A few days ago a typical son of the Emerald Isle, although he had found a hard lifework, far from his native land, appeared before the anthracite coal commission. Before many minutes had been taken up in examining him the chances came for which he waited, as naturally as a duck waits for the rain. He testified that he had been half killed in the mines twice. The judge remarked that he must be dead, then.

“But no, one side got well, before the other side was killed,” quickly replied the Irishman.

In a minute the commission of staid and dignified men and the judges and the lawyers were all smiling; like a flash of a sunbeam the mirth went from countenance to countenance, that had all been serious with the weighty problem confronting them; and the weary problem of existence that had cast a gloom over all gave way before the irresistible humour of the old Irishman. Twice in his life, as he testified, the old fellow had been half killed. For thirty years he had lived in the under-world, always in debt to the company and only once in 17 years had he received his wages in actual money. Here was a man over 60 years of age, whose life had run in dark and tragic lines, one who had been a slave to the mines and one in whom it would seem that all joy had been stifled forever. Yet as soon as this old Irish miner appeared before the prosperous and scholarly committee, it was not ten minutes before his humour irradiated the dry proceedings and set the table in a roar.

How fragrant and perennial is that flower of Irish humour! exclaims a comment on this incident. How like a star it is too, shedding its kindly beams through the darkest night! Indeed, it is both star and flower, diverse as they may be; for could anything be more delightfully wayward, deliciously perverse and serenely inconsistent than this same Irish humour! Being ever the twin sister of pathos, one will find it blooming in melancholy sweetness by the new-made grave upon the wind-swept hill. But if we may be pardoned the Irishism, it is also the twin sister of joy and so, may be found frolicking where the sunshine of life falls brightest. Out of the dark and grimy mine came this old son of the night, bringing with him his boon of joy as undying in the Irish heart, as the beautiful shamrock is in the Irish meadows. Bless God for the poor yet rich old miner, Jim GALLAGHER! And here’s hoping that his Christmas stocking, if he had one, was filled with the good things of this world. He gave the entire country that priceless blessing, a good laugh. So we say, Let ‘er go, GALLAGHER. (Fermanagh Herald)

12 Dec. 1911 Curios of a Word Collector

A public lecture in connection with the Raphoe Young People Guild was given Thurs. evening by Rev. J. Craig WALLACE entitled “Curios of word-Collector” or “Ulster phrases and sayings, their origin, and significance”. The lecturer said he who would know the Ulsterman must endeavour to discover the origin, history, and development of his languages, for the life of every people is pictured in their speech. The rise of this Irish dialect of the English language dates from about the middle of the 17th century. Three main streams have combined in the formation of the Anglo-Irish speech. First of all there is the Irish language itself. Like all introduced languages, English in Ireland, has been greatly influenced by the literal translation of the domestic idiom into the introduced tongue, as well as by the absorption of native words. Even educated people in Ulster are constantly using expressions that are word for word translations of the Irish idiom.

For instance;

“It takes a good deal out me”

“What hurry is on you!”

The weather was against him”

“He got into trouble on the head of it.”

“He stood behind the door the way he wouldn’t be seen”

and very many others, all of translations of the Irish idiom.

Then such Irish words “shanty, galore, smithereens, meskin, stook, smur, bother.” Further, there is the remains of the old English dialect of the Elizabethan time, the English of Shakespere. which is found in common use, such words as “aye, troth, drouth, quoth, tryst, black-a-vised, posies, lusty, as lief”, all Shakesperian.

Again, certain English words were used as translations of Gaelic words, but were far from being equivalents, and the native would continue to think in Gaelic, while he clothed that thinking in English. This gave rise to expressions that are the despair of Englishmen. Very many of our phrases and words are so vivid, so capable of conveying an absolute and final thought, that it would be a distinct loss to our speech to abandon them. Your average peasant will convey a few terse and vivid phrases, in a speech that is full of imagery and poetry, thoughts that cannot be so conveyed at all by the circumlocution of the better educated. He speaks pictures, for every word was over a poem and every phrase picture; the scholar speaks thoughts. Let no one be pedantic here, or pretend to be offended at the discussion of these phrases. Semi-educated vulgarity is the worst form. They are the speech of the people and are full of interest and delight to the scholar. Vulgarisms are forms of speech invented by people. But survivals of usages that were once correct, are antiques, and not vulgarisms.

Such words as “leif, afeerd, childer, stime, nor (for than), wit (for sense), once (for as soon as) were once classical and proper. Several sayings in the current speech were here referred to. Another class of sayings and phrases and names that have arisen out of misconceptions was illustrated.

Lough Salt, in Donegal, for example: so too.

“Man a man.”

“Deer knows,:

“He will never set the temse on fire.”

Many phrases are the echo of a loose association with religious ceremonies as; “By the hole in my coat,” “Hokey. O.”

Many phrases are misused, such as

“Bother.”

“Body”(Bodagh)”

“Leathering”

“Re Ra” (Righ Rath)

Explanations were given of

“On tick”

“Scran”

“Ohone-a-Righ”

“Hobby”

“As mad as a hatter”

“Daligone”

“Delfan”

“Dark” (of peats)”

“Cosnent”

“Chin-cough”

“Bediril”

“Spunk”

“Smullock”

“Smallock”

“Thraneen”

“Tory”

“Mooled”

“Himself” (the master the house)

“Cant” (an auction)

“Oxtered”

“The churn” (harvest feast)

“Sugy” (calf)

“Chex” (to the cow)

“That beats Banagher”

“Go to grass”

the Ulster use of “brave” which is Shakespearian and “bold,” which in current speech, does not always convey the idea of courage;

“Fingering” (wool)

“Grogam” and “Capers”

The use of assertion by the opposite is a favourite Ulster and Irish form of speech; “I wouldn’t be sorry to get away” (equal to I would be glad) “Nothing the better o’ that.”

“Its little for blushing they care down there” (Lever)

The memory is fairly spoiled in me wid mindin’ to forget”

The Ulsterman has withering names for inefficient things and men;

a bungling workman is “Burn the gully.” A tongue that would “clip clouts” and a nose that would “smell a needle in a forge”, for intensiveness and picturesque imagery are unequalled perhaps, in any vernacular in the world.

Shakespeare has “to speak daggers;’” Aristopheres has “to talk mustard”, the Psalmist says “his words are drawn swords”; the Irishman is a match for any in the swift rapier thrust of his invective.

The Ulsterman has playful names for things and men that are often very pithy. Illustrations were given from “Moira O’Neill.” “Will Carlton” and others of playful exaggerations that prevail in the current speech. Not to know the people, their language, humour, drollery, and fun – a language sparkling with image and symbol, thrilling with the very spirit of poetry and studded with gems of speech, is to be ignorant of the great unwritten epic in Ulster

“Old scenes, old songs, old friends again.

The vale and cot I was born in:

O Ireland, up from my heart of hearts

I wish you the top of the mornin’. (Londonderry Sentinel)

22 Jan. 1914 Ulster Humour

No matter how large the bride’s fortune, the Ulsterman (we are told) generally grumbled over the marriage fee. “Would’t half a crown timpt ye?” asked a bridegroom of the officiating minister when the clerk demanded the usual five shillings. Ulstermen take a calvinistic view of destiny. When a minister expressed his surprise that a husband should be found for an old and portionless woman, he was briefly reproved in the reply “There’s critters for critters.” (Liverpool Echo)

7 Mar. 1923 Specimens of Ulster Humour

by John J. MARSHALL

“All to the one side like Clogher”, a well-known saying arising from the houses being only on one side of the street, the demesne wall, of what was formerly the Bishop’s palace occupying the other side. An able and rather original Tyrone clergyman, one day in the course of his remarks on the 122nd Psalm said, “You see, brethren, that Jerusalem was compactly built togather. It was not a long straggling street like Cookstown; it was not like Clogher, all built on one side, with the Bishop’s palace on the other; but it was a compact town like Dungannon, where every man’s purloin lay on his neighbour’s gable.” There used be a favourite rhyme with schoolboys;

“Augher and Clogher and Fivemiletown, Sixmilecross and seven mile roun’.”

Then there is the complimentary saying;

“Full and flowing over like Ballynahatty measure.”

Ballynahatty is in the vicinity of Omagh and gives the name to a Presbyterian congregation.

Another Tyrone appellation is “Killyman Wrackers,” which was probably applied to a company yeomanry, or body of private individuals belonging to the district that had distinguished themselves in the troubles between the Peep-of-Day Boys and Defenders in the last 10 years of the 18th century.

Every Dyan man, whatever part of the world he may be found in, is proud to announce that he is from “No. 1 the Dyan,” this little Tyrone village being the seat of the premier Orange lodge of the Order.

Moy (famous for its horse fair) is generally spoken in County Tyrone as “The Moy”, and the Irish State Papers of Queen Elizabeth’s time, Newry is always written as “The Newrie.”

Sweet County Down shares with another county the saying; “Antrim for men and horses. County Down for bonny lasses,”

Newry is known as “the frontier town,” and “coming like the half of Newry” denotes precipitate haste. It has also been immortalised by Swift, who must have been familiar with the town, during his long visit to Sir Arthur ACHESON, at Markethill, in the bitter couplet;

“High Church, low steeple.

Dirty streets and proud people.”

Then we have “Banbridge beggars” and “a long Banbridge man.” In the vicinity Seapatrick, locally known as ‘Blazestown,’ while on long ridge of hill not far distant, there are situated five farm-houses which when lit up on winter nights are known as “the five lights.” Rathfriland is “the hilly town,” and Miss M’KAY, in her charming book has sounded the praises of the district around Kilkeel as “Kin’ly Mourne.”

Holywood is known as “the town of the maypole,” claiming as it does, to have the only one of these interesting survivals of a charming bygone custom in Ireland.

For those who like plenty of stir and movement, a suitable place of residence would be;

“Sweet Dromore, where they keep no Sunday,

And every day is like an Easter Monday.”

There used to be horse races held in Dromore (County Down) on Easter Monday, hence the saying.

In Monaghan the “Green Woods of Truagh,” now, alas, no more, gave their name to an Irish air; there is also the saying; “The whole world and the half of Truagh,” and “Amackalinn, where the stirabout’s thin and Tereran for the hairy butter.” These are in the Barony of Truagh.

It was through Emyvale, a Monaghan village near the Tyrone border, that a beggarman passed from one end, to the other without receiving charity, upon which turned and apostrophised it in a couplet that has stuck ever since;

“Emyvale, O Emyvale.

If you were as free from sin as you are from male (meal).

You would be the happy Emyvale.”

Castleblaney is always associated with besoms, there being an Irish tune named “Castleblayney Besoms,” in connection with which there are a couple lines of an old song, probably the remains of the original words belonging to the air; “Castleblayney besoms, sold in Mullacrew.

If I can get two a penny, what is that to you?”

In the neighbouring county we have “Cavan bucks”. In the midlands anything extraordinary, or out of the common “Bangs Banagher” and as is well known, “Banagher bangs the deil.”

It is not so well known that there is another Banagher in County Derry which has the saying “Banagher sends”. A person endowed with an excess quantity of adipose tissue said to be “Beef to the heels like a Mullingar heifer.”

The foregoing are but a few of the many local names and rhymes that are scattered all over the country. There must be a great number still unchronicled, which should be collected and set down ere the modern march of the intellect, has caused to be forgotten, these minor rhymes and sayings of an earlier and a simpler day. (Northern Whig)

Illustrations from ‘Mr Punchs Irish Humour’ by Charles Keene, 1910