Compiled and transcribed by Teena from the Fermanagh Herald and the Tyrone Constitution

Friday, 30 Aug. 1889 Plantation Papers – County of Tyrone

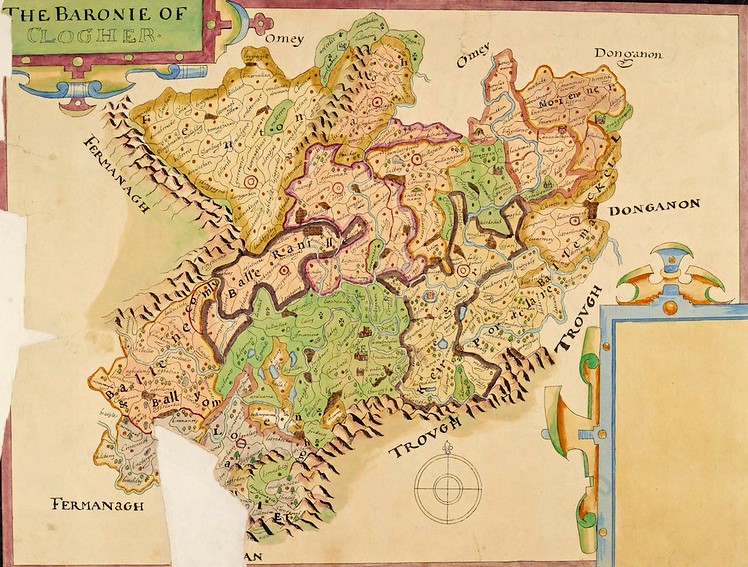

Tyrone is occasionally spoken of as the premier county of Ulster because it is the largest and most central fragment of that region which formed the ancient principality of the O’NEILLS. In more modern days that great portion of our Northern province has been curtailed in almost all its boundaries, but the present county still contains the seat of its early government and is associated more intimately than any of the other counties in Ulster with the history and traditions of the great family above named. In the year 1584 that portion of the principality which lies south of the Blackwater was shired off and became the County of Armagh; and in the year following another great fragment lying between the Bann and the Foyle was also shired off and was subsequently known, at least for a time, as the County of Coleraine. At a later period or in 1608, a third large and very valuable fragment known as the barony of Loughinsholin was taken from what had been the principality and added to the County of Coleraine, to form the present County of Londonderry. But still the remaining part the principality, now known as the County of Tyrone, is of very ample dimensions – something over thirty eight miles in length, from the town of Caledon, on the Blackwater, to the mountain of Croagh, a little eastward from the Pass or Gap of Barnesmore; and not less than thirty miles broad along its western border, by Strabane and Loughderg. This vast sweep of territory contains 467,175 Irish acres, or 751,387 acres of English measure. These figures may be perhaps somewhat under the mark, if it be fact, as we have seen stated, that the county contains 450,286 arable acres English measure, 311,867 acres uncultivated, 11,981 acres under wood and the remainder water, excepting small portions around several country towns. When the commissioners of Plantation reached Tyrone from Armagh, they found that it contained four large baronies named respectively – Dungannon, Clogher, Omagh and Strabane. These have been since sub-divided, so as to make eight modern baronies. The commissioners adopted the old baronial divisions as their plantation precincts, excepting in the case of Dungannon, which because of its great extent, they divided, naming the lower, or northern portion, the precinct of Mountjoy. They found that all the lands in Tyrone belonged to the Crown, excepting the Church lands and excepting about 5,000 acres lying on the western side of the Blackwater, which had been granted by Queen Elizabeth to Sir Henry Oge O’NEILL and were then held by his heirs. These lands comprised the ancient Irish territory known as Mointerburn, and were the inheritance of Sir Felim Roe O’NEILL, who resided at Kinaird on the Blackwater. The termon and herenagh lands in Tyrone, although originally belonging to the early Irish Church, were found by the commissioners to have been virtually in the hands of the minor septs i. e. of the clansmen for many centuries and such being the case, they fell to the Crown, as all lands held by the people were confiscated by the attainder of the Earl of Tyrone. The barony of Clogher was the recognized territory or “country” of Sir Cormac O’NEILL, a younger brother of the Earl, but there is not a word in any of the Commissioners’ reports to indicate what had become of him, or on what plea they had appropriated his lands. It was taken for granted no doubt that Sir Cormac held his estates by grant from the Earl and that the attainder of the latter was enough, as forfeiting all the lands of his tenants, as well as those held immediately by himself. When the Earl unexpectedly left Ulster – an event which the Government pretended to regard as deeply offensive, although it was exactly what they wished and wanted – no one was more surprised or upset than Sir Cormac and he was the very first to bring intelligence of it to CHICHESTER. Sir Cormac had been living on peaceable terms with the Government since the close of the war in 1602; so much so indeed that the Earl does not appear to have given him any intimation of his own intended movements; but CHICHESTER and DAVYS suspected Sir Cormac of complicity with the Earl, that when he hastened to Dublin to let them know of the flight from Lough Swilley he was seized and soon afterwards sent off to the tower in London, where he pined a woeworn captive for the space of eighteen years, until death released him. However, during the movements of these commissioners throughout Ulster an incident occurred which must have reminded them very unpleasantly of the way in which they had dealt with Sir Cormac O’NEILL. As they journeyed from Lifford to Enniskillen the Lord Chief Justice WINCH, who was of the party, became seriously ill and was sent by CHICHESTER to recuperate at the residence of Sir Edward BLANEY, near Monaghan On the way thither WINCH informs us that he “was in his travel enforced to Sir Cormac, M’Baron’s house, now prisoner in the Tower.” In other words, he was obliged to take refuge for a time in the Castle of Augher. “His lady,” continues WINCH, “gave us house room, but had neither bread, drink, meat, nor linen to welcome us, yet kindly helped us to two or three muttons from her tenants”. This lady was a daughter of the chief house of the O’DONNELLS of Donegal and would probably have been offered a little patch of her husband’s lands on plantation conditions but she died soon after WINCH’S enforced visit. She had already, however, been doomed to feel and see the commissioners at work around her, for they commenced with the barony of Clogher during their work in Tyrone. This barony contains 97,569 acres and comprises part of the parishes of Aghalurcher, Donagheavy and Errigal Trough, with the whole of the parishes of Clogher and Errigal Keerogue. Its chief towns and villages are Clogher, Agher, Ballygawley and Fintona.

The commissioners found in this barony or precinct of Clogher only 12,500 acres of arable land, which they marked off into ten proportions – seven small, one middle and two great. These proportions were soon afterwards allotted to the following eight English undertakers –

Sir Thomas RIDGEWAY, Knight

John LEIGH, gentleman

Walter and Thomas EDNEY, Esqrs.

George RIDGEWAY, gentleman

William PARSONS Esq.

William TURVIN, gentleman

Edward KINGSWELL Esq.

William CLEGGE, gentleman

When the above named planters had been in possession of their several estates in Clogher for a year, Sir George CAREW made the following report of their progress;

“Sir Thomas RIDGEWAY, vice treasurer and treasurer of wars in Ireland. 2,000 acres; has appeared in person; his agent Emmanuel LEY, resident this twelvemonth, who is to be made a freeholder under him; Sir Thomas brought from London and Devonshire, the 4th May, 1610, twelve carpenters, most with wives and families, who have since been resident, employed in felling timber, brought by Patrick M’KENNA, of Trugh, County Monaghan, none being in any part of the barony of Clogher, or elsewhere near him; viz: 700 trees, 400 boards and planks, besides a quantity of stone, timber for tenements, with timber ready for setting up a water-mill; he is erecting a wardable castle and houses, to be finished about the next spring; ten masons work upon the castle and two smiths; one Mr. FAREFAX, Mr. LAUGHTON, Robert WILLIAMS, Henry HOLLAND and three of said carpenters, are to be made freeholders; other families are resident, wherewith he will perform all things answerable to his covenants.

Edward KINGSWELL, 2,000 acres, has appeared at Dublin and taken possession personally; returned into England to bring over his wife and family; his agent, William ROULES, has money imprested for providing materials to set forward all necessary works.

Sir Francis WILLOUGHBY, knight (who sold out to John LEIGH), 2,000 acres; has taken possession personally; William ROULES and Emanuel LEY, in his absence, employed in providing materials for buildings; 200 trees felled and squared.

George RIDGEWAY, 1,000 acres; took possession in person; his agent is resident since March last; some materials ready to place; intends to go forward with building his bawne; some freeholders and tenants to inhabit, but work done.

William PARSONS, the King’s surveyor, 1,000 acres; took possession personally; his brother, Fenton PARSONS, his agent, is resident since March last; has provided materials for building; has two carpenters and a mason and expects four Englishmen, with their families to come over shortly; no work done.

William CLEGGE, 2,000; has not appeared, nor any for him; it is reported he passed his lands to Sir Anthony COPE, whose son came to see the same and returned into England; nothing done; by letter he desires to be excused, promising to go on thoroughly with his plantation next spring.

Captain Walter EDNEY, 1,500 acres; took possession personally; his son-in-law resident since March last; provision made for building a house, the foundation laid; six families of English in the kingdom that will come to plant and settle next spring.

William TURVIN, 1,000 acres; took possession in person; his brother resident since March last; has provided materials for building; agreed with four families to come out of England the next spring to plant, who promised to bring other five families; intends to go shortly in hand with building a bawne and a house; but nothing done.”

The progress of these planters during the first year may seem slow, but their difficulties at the commencement must have been serious and their purses generally were but light.

1 Sir Thomas RIDGEWAY exchanged his proportion of Portclare and Ballykirgir in 1622 for the title and dignity of an earldom. Sir James ERSKINE came to Ulster, bringing with him from James I. the power of creating an earl and this power he was permitted to utilise best he could. He appears to have been fortunate in meeting a customer, for the exchange was very simply and speedily made, RIDGEWAY becoming thenceforth Earl of Londonderry, and Sir James ERSKINE the owner of the lands in Clogher that had been grunted to the former.

2 John LEIGH was an engineer by profession and came to Ulster with the Earl of Essex in 1572. Before the time of the Plantation he had visited many localities in this province as an engineer and knew many of its leading Irish inhabitants. He appears to have bought the proportion of Fintona from Sir Francis WILLOUGHBY even before the latter had taken out a patent, for grant was made in LEIGH’S own name. The engineer seems to have had no particular taste for planting, for instead of bringing strangers on his lands, he let them off to the Irish occupants at the risk of being forfeited for so doing. At his death he was succeeded by his nephew, Sir Arthur LEIGH, who sold the estate to Captain James MERVIN, or MERVYN.

3 Walter and Thomas EDNEY, who were brothers, came to Ireland as servitors during the war against the Northern earls and were generally employed as spies. Walter had received such rigorous treatment as a spy in Spain that he died about 1610 and Thomas was classed among such servitors “as would be content to undertake, but not to build castles unless by extraordinary helps and encouragements.” Both the brothers however, had soon disappeared and their proportion of Ballyloughmaguiffe was known for some time as the Manor of Ridgeway and eventually as the Manor of Bleasingbourne, having passed through many hands.

George RIDGEWAY came from Devonshire and was the younger brother of Sir Thomas. He ranked amongst such servitors as “undertook of themselves with some help and encouragement” obtaining the proportion of Ballymakell, which adjoined his brother’s lands at Augher and which he named the Manor of Thomas Court, probably in honour of his brother. (Tyrone

History & Antiquities of Clogher – An Interesting Lecture by the Very Rev. James MacCAFFREY D.Ph., Maynooth

4 Apr. 1908

Last week Very Rev. James MacCaffrey, D.Ph, Maynooth, delivered a lecture on “The History and Antiquities of Clogher” in the courthouse, Clogher. There was a large and appreciative audience who followed the lecture with the greatest interest.

When invited to address this meeting tonight I resolved to take as my subject, the history of Clogher and the neighbouring districts. I selected this subject not because it was the least difficult to handle in a popular style, but because it is evident to anyone acquainted with this part of the country that the old traditions and legends for which Clogher was once famous are fast being forgotten and that the vast majority of the people are almost on the same level as the late high Sheriff of Tyrone, who seems to think that the history of Clogher begins with the ordeal of the English and Scotch planter. in this portion of the country. In fact, if you ask the ordinary man in the district for some information about Clogher, he will probably tell you that it is a station on the Clogher Valley Railway and that it is remarkable for being built all to the one side, for a very commodious workhouse, for it’s police barrack, which had once the honour of being a bridewell and for its great lammas fairs, famous in the old days as the sporting fair.

Clogher had been famous as the royal residence of the Kings of Oriel, long before St. Patrick visited this country. The Kingdom of Oriel included Monaghan, Armagh, Louth, South Tyrone and a good proportion of Fermanagh. Clogher was selected as the royal site of the princes of East Oriel and no better selection could have been made. Standing in the “Rathmore” in the grounds of the bishop’s palace, it commanded a view of the richest and fairest district in Tyrone. On the northern side towered the wood-coated hill of Knockmany, on whose summit, according to the legends, is buried the Queen Baine, the foundress of the Rathmore. Knockmany has been celebrated in song and story and by none more so than by two gifted authors, natives of the parish, CARLETON and Rose KAVANAGH. On the other side towards Monaghan, stretch the mountain range of Sliabh Beagh, which got its present name from one of the leaders of the first colony that settled in Ireland. He is supposed to have been buried on the top, of what is since known as Carnmore, in the parish of Clones. It is in these range of mountains that CARLETON lays the scene of some of his best stories, one of them, “The Midnight Mass,” sad and gloomy, the other, “How the Gauger was outwitted,” being full of life and humour.

The origin of the name Clogher has been variously explained. The usual explanation of the name is that it means “The Golden Stone.” It is stated that when Ireland was yet pagan there stood at Clogher a famous pillar stone, or idol worshipped by the people of the north. Its name was Kermand Kelstach, and Kermand Kelstach was the great idol of Ulster, worshipped by the people and consulted by them in all their difficulties. It was covered with gold that had been, then, discovered in Ireland and on account of the presence of the “Cloc’ Oir;” (?) in this part of the country, the whole district got the name of Clogher. After the inhabitants had become Christian the stone was still faithfully preserved, possibly as a pedestal for a cross and in the fifteenth century Cathal MAGUIRE, a distinguished ecclesiastic of Clogher Diocese, tells us that the “Cloc’ Oir;” (?) still was to be seen standing in the porch of the Clogher church. It is said that in the beginning of the 17th century, when the O’NEILL power was broken and when the reformation party had got the upper hand about Clogher, the Catholics hid the “Cloc’ Oir;” (?), lest it should fall into the hands of the invader.

That there was a great idol at Clogher is indeed very probable,but that Clogher got its name from “Cloc’ Oir;” (?) is entirely unlikely. The oldest reference to Clogher is in some Irish documents of the latter half of the seventh century and it is then referred to as “Clocair mic Caihin” (?) – Clogher of the son of Daimhin. It is impossible that the form of “Clocar” (?) should have come from “Cloc Oir” (?) while on the other hand, the fact that we find the name Clogher so common a place name in Ireland suggests the natural derivation ‘Clocar’ (?) meaning a stony place, just as ‘rrrutar’ (?) is derived from ‘rrut’ and means a place full of streams. Though the land in the vicinity of Clogher is not remarkably stony, yet the whole district over which Daimhin ruled might well be referred to as stony. The Daimlain after whom Clogher is called “Clocair mic Oaimin” (?) was a descendant of the COLLAS, founders of the kingdom of Oriel and it is after him that Altadavin received its present name. The old name of Clogher explains satisfactorily the form Altadavin.

Now, when St. Patrick was engaged in preaching the gospel to the Irish, it was only natural that Clogher should receive a great deal of his attention. In his tour of conversion, he generally took care to visit the residence of the King, or Chieftain, for if the King, or chieftain accepted the christian faith, his followers were certain to imitate his example. Clogher was, as we have said, is the seat of the princes of West Oriel and St. Patrick resolved to visit the “Rathmore,” or royal residence.

He approached Clogher from Dungannon, passing by Ballygawley and crossing the Blackwater near the present village of Augher. It was possibly in crossing the Blackwater that the incident happened which is referred to both in the Lives of St. Patrick and St. Macartan. St. Macartan was St. Patrick’s champion, his assistant in difficulties and his protector in dangers. He had accompanied the national apostle on his tour through Ireland and he was now grown old. In carrying St. Patrick across the river he showed some signs of discontentment and on St.. Patrick’s enquiry as to the cause, he pointed out that all his companions had already been provided with fixed churches, while he alone had been forgotten. St. Patrick immediately took the hint and he hastened to assure him that he would give him a church that should not be too near Armagh, but that at the same time, should not be too distant for a friendly visit. This is how St. Macartan was appointed first bishop of Clogher. There are some, indeed, who contend that, St. Patrick himself was the first bishop of Clogher, but although this contention is not without some support, yet the weight of historical evidence goes to show that St. Macartan is justly regarded as the first bishop and patron of the See.

In the Life of St. Macartan it is stated that St. Patrick said to the Saint on their approach to Clogher “Go in peace and build yourself a monastery on the green before the Royal palace of the men of Oriel, where you will rise in glory hereafter. The abode of those who seek mere earthly goods will be laid desolate, but thine will daily be enlarged and from its sacred burial ground very many will rise to the blessed life.” And well has this prophecy been fulfilled. The Kingdom of Oriel has long since fallen, the princes of Oriel have disappeared and their successors, the Hy Nialls, are no more; the royal palace of Clogher is levelled to the ground and its very site is almost unknown; but still the faith that was planted by St. Macartan is still strong and the successor of St. Macartan still rules over the lands committed to the Saint’s care by the apostle of Ireland.

Echu was the reigning prince at Clogher when St. Patrick presented himself at “Rathmore.” The prince received the saint and though he himself refused to accept the christian faith, one of his sons, Cairbre, was converted, as was his daughter, Cuinu. He gave a portion of ground for the erection of a monastery and many of his followers deserted the druid worship.

St Patrick left Clogher and went in the plain of Mog Leinain, which, stretching from Sliabh Beagh to the Blackwater, embraces the present parishes of Clogher, Errigal Keerogue, and Errigal Truagh. Here, amidst the oak groves of the hill of Altadavin, was the seat of the druids who ministered at the court of the Princes of Oriel at Clogher. It was for this reason that St. Patrick directed his steps towards Altadavin and standing by the druid stones, on the spot where the people still point out the altar and well of St. Patrick, he preached to the assembled multitudes and proved the superiority of the christian priesthood over their pagan rivals. From Altadavin, St. Patrick proceeded towards the present parish of Tyholland. It is remarkable that when a dispute arose between the men of Uladh and men of West Oriel as to the place where St. Patrick should be buried, it was agreed by both parties that from the neutral territory of Clogher, two oxen should be brought and yoked to the car on which the coffin lay and that wherever they went, there, the mortal remains of St. Patrick should be laid to rest.

On the departure of St. Patrick, St. Macartan remained at Clogher and built his monastery in front of the royal residence, probably on the site of the present Protestant Church of Clogher. The prince, Echu, had not been converted and disliked St. Macartan, first, as being a Christian and secondly because he was a stranger in the district. But his family were more kindly disposed and the daughter of the prince, Cuinu by name, consented to take the veil and become a nun. A convent was founded for her near the monastery and standing within the demesne on what is now known as the Nun’s Hill. The church and monastery of St. Macartan have long since been replaced. No portion of them is to be seen today and no relic of them has come down to us, if we except the Domnach Airgit, which is said to enclose a copy of the gospel given by St. Patrick to St. Macartan when he was parting with him at Clogher. The old cross discovered, I think, by Father Raphmun and erected in front of the present church, is indeed very ancient, but it is, in my opinion, of a date long after the time of St. Macartan.

St. Macartan died about the year 505 and was buried within the enclosure of his monastery. A handsome chapel was erected over his tomb, but the tomb and chapel have long since disappeared. The site is probably to be sought for in the centre of the present graveyard of Clogher. His memory was held in the deepest veneration by his successors in Clogher, and one of them, Patrick CULIN, composed in the 15th century the beautiful ode which is recited on his feast day;

A noble feast we celebrate,

A holy man we venerate,

Great Macartan it is he,

Hear us, blessed Trinity.

A confessor in faith was he,

A virgin in his chastity,

A martyr too, in heart and will,

An apostle preaching still.

No suppliant ever came in vain

Oppressed by toil or weary pain,

But by the grace his blessing shed

He departed comforted.

Sight and hearing were restored,

Fled the leper’s spot abhorred,

The dying from their deathbed rose,

As the priest, Macarten, chose.

Thee God as three in one we own,

From whom the precious grace comes down,

By which the clergy here are blessed

With earnest of eternal rest.

The church at Clogher gave its name to the whole diocese over which the successors of St. Macartan ruled. It was remarkable as being one of the largest and the best endowed of the Irish dioceses. At one time it extended from the Bundrowes River, beyond Bundoran, to Clogher Head, in the County Louth, embracing a great part of Tyrone, a portion of Donegal, the whole of Fermanagh and Monaghan and the richest portion of the Co. Louth. It was during the episcopate of Bishop O’BROGAN, in the middle of the thirteenth century, that the old diocese of Ardstraw in Tyrone, was separated from Clogher and united to Derry, while at the same time the deaneries of Dundalk and Drogheda were handed over to the Primate of Armagh.

The diocese of Clogher was also remarkable for the fact that during the whole time after the English invasion, when the English were endeavouring to get a voice in the appointment of bishop and to secure the election of an English bishop, the English crown had no influence in Clogher. Edmund COURCY was the only Englishman who ever sat as the Catholic bishop of Clogher. As a result, the bishops of Clogher were strong supporters of the O’NEILLS and the native Irish and in every struggle for their native land, the bishops of Clogher led the way.

The Hy-Niall princes, formerly confined to the little promontory of Innishowen, began to extend their conquests eastwards in the fifth century and soon they drove back the princes of Oriel and took possession of most of the country formerly occupied by West Oriel. It was from these descendants of Eoghan that this county got its name; Tir-Enghan, or Land of Eoghan. The Cinel Feradhag, one of the septs of the O’NEILS, got possession of the barony of Clogher and in this way the family of MacCAWLL (mac catmaort) (?) became the principal family in this portion of the country. Many of the distinguished ecclesiastics of Clogher were attached to the diocese of Clogher. In after times the family was anglicised into CAMPBELL, CAULFIELD, HOWELL (HEWELL?) and possibly M’CAUGHEY and from the presence of so many families bearing these names till the present day, it is evident that in spite of all the wars and expulsions and evictions, the old tribe of Cinel Feradhag has not been completely blotted out in the barony of Ctlgher.

The O’NEILL’S ruled the greater portion of Northern Ireland as sovereign princes even after the English had conquered the rest of Ireland. They were crowned with solemn ceremony on the family stone at the rath of Tullyhogue, just as the MAGUIRES were crowned on the hill overlooking the town of Lisnaskea. The ceremony is well described by DAVIS, whose poem I shall merely quote;

Come, look on the pomp when they make an O’Neill,

The muster of dynasts O’Hagan. O’Sheil, O’Cahan, O’Hanlon, O’Breaslin, and all,

From wild Ards and Orior to rude Donegal.

St. Patrick’s Comharba, with Bishops thirteen,

And Olaves, and Brehons and minstrels are seen

Round in Tuloch Oge Rath like bees in the spring,

All swarming to honour a true Irish King.

Unsandalled he stands in the foot-dinted rock,

Like a pillar stone, fixed against every shock

Round the round in a rath on a farseeing hill,

Like his blemishless honour and vigilant will,

The grey-beards are telling how chiefs by the score

Have been crowned on the Rath of the Kings heretofore.

While crowded, yet, ordered, within its green ring.

Are the dynasts and priests round the true Irish King.

The Chronicler read him the laws of the Clan,

And pledged him to bide by their blessing and ban;

His skien and his sword are unbuckled to show

That they only were meant for the foreigner foe;

A white willow wand has been placed in his hand,

A type of pure, upright, and gentle command,

While hierarchs are blessing the slipper they fling,

And O’Cahan proclaims him a true Irish King.

Thrice looked he to Heaven with thanks and with prayer,

Thrice looked to his borders with sentinel stare,

To the waves of Lough Neagh, the heights of Strabane,

And thrice on his allies, and thrice on his clan.

One clash on their bucklers – one more -they are still,

What means the deep pause on the crest of the hill?

Why gaze they above them! A war eagle’s wing.

‘Tis an omen! Hurrah for a true Irish King.

Like their predecessors, the princes of the O’NEILLS were generous protectors and benefactors of the monastery and diocese of Clogher. It was during their reign that so many of the Termon lands, scattered over Tyrone, Fermanagh and Monaghan, were bestowed for the support of the clergy and the maintenance of the schools. This was useful at the time, but it was unfortunate afterwards, for at the Reformation period, owing to the richness of the diocese of Clogher, we find a regular scramble among the Protestant planters as to who should get permanently the Bishopric of Clogher. The monastery of Clogher continued to develop under the protection of such bishops as Christian O’MORGAIR, who is described as a man excelling in wisdom and piety, a shining light, enlightening both the clergy and laity with his holy works and godly admonitions, the common father and pastor of the Church. According to St. Bernard he and his brother, Malachy of Armagh, were the two pillars of Ireland. The bishop. Matthew MacCASEY (1287) erected a chapel over the sepulchre of St. Macartan, surrounded the whole churchyard with a wall and made way beautiful to the church. It was at this time also, that the episcopal residence, which was close to the present Protestant church of Clogher, was removed to the site of the present deanery of Clogher, owing to an arrangement between the monks and the bishop. In the fourteenth century we find that the Church of Clogher and all the houses were burned and especially in the year 1396 (1306?) we read that the Cathedral, the Chapel of St. Macartan, the (court?) of the bishop, thirty of the houses, and the whole vestments and sacred vessels were destroyed by fire. The buildings were probably constructed for the most part of wickerwork and this will account for the many burnings, which we read of at this period in the Irish Annals.

It not is not easy to identify the site of all the ecclesiastical buildings about Clogher. But from a map of Clogher in the year 1609, it would appear that at this period the bishop’s residence stood on the site of the present deanery of Clogher. The cathedral of Clogher stood in the very spot now occupied by the Protestant Church, while round it, taking in the road and the site of the houses on the street opposite, stretched the graveyard. Probably in the centre, or at the entrance of this stood the old cross, portion of which, has been again erected in front of the Protestant Church. Further down towards Augher stood the monastery, the site of which it is not easy to determine at the present time, so completely have the invaders destroyed every vestige of the earlier ecclesiastical buildings.

18 Apr. 1908

During the disturbed reign of James II, the Clogher Valley was once more the seat of war. When James II was proclaimed Dublin and a Jacobite was appointed Lord Lieutenant of Tyrone, the Protestant landowners were uncertain which cause to espouse. They wished to preserve their estates and hence many of them hesitated till they could foresee which side was likely to be successful. But there was no hesitation amongst the sturdy farmers of Ulster, especially amongst the Presbyterian farmers. Enniskillen refused to accept a Jacobite garrison and Derry closed its gates and boldly raised the banner of William III. David CAIRNS of Cecil Castle, was the heart and soul of the spirited defence of Derry, while Hugh MONTGOMERY of Derrygonnelly, stepped manfully into the post of danger, when many of his brother landowners wavered.

The garrison of Enniskillen learned that Augher Castle was held for James II. They made a sally from Enniskillen, marched through the Clogher valley, seized all the cattle and provisions, stormed Augher Castle and took possession of it in the name of William of Orange. From Clogher, they turned through the mountains, occupied the Eccles House at Clones, and returned to Enniskillen victorious.

The war ended in the well-merited defeat of James II and it is a pity that the Irish Catholics ever united their fortunes with the Jacobite cause. But there is one point to which I should like to direct the attention of those who so faithfully celebrate the memory of Derry, Aughrim and the Boyne. The men who should have led the way in the fight against James II, held aloof till the victory of his opponents was well nigh certain. The real fighting was done by the sturdy Presbyterians of Ulster, yet in the end, when the spoils of conquest were being distributed, the episcopalian landowners got the lion’s share and the Presbyterians were left out in the cold. In fact, they were excluded from all offices of trust and they were treated almost as contemptuously, as their Catholic neighbours.

In the Union struggle, Tyrone was well represented. It is interesting to observe that the ancestors of the men who now oppose an Irish Parliament so bitterly, struggled bravely to prevent the union. The Earl of Belmore and his son, Lord Corry made an honest fight against bribery and corruption. The borough of Augher was a rocket borough of the Marquis of Abercorn, one of the “hungry Hamiltons,” as they were called and needless to say, the members for Augher were safe. The bishop of Clogher, relying on the charter of 1629, nominated the members for Clogher, or had them elected by his own servants. His nominees on this occasion were GARDNER and ANNESLEY. The opponents of the union questioned the bishop’s right of nomination. They canvassed the freeholders of the district, held an election of their own, and two opposition members were returned – KING and BALL. A Parliamentary commission was appointed to investigate the claims of the rival parties, but in the meantime ANNESLEY was appointed chairman of the committee which prepared the Union. In the end, it was decided that the bishop’s claim was an usurpation, that he had no such privilege as he claimed. His members were unseated and BALL and KING took their places as the members for Clogher.

It was BALL who was the innocent cause of a rather serious incident in the parliament. The story is told, by BARRINGTON, an ex-M.P. for Clogher, in his “Rise and Fall of the Irish Nation.” BALL was of a rather impetuous temperament. He declared that the easiest way to prevent the union would be to throw a bomb into the assembly and blow the whole corrupt lot to eternity. This statement was made in a public room and shortly after, during a heated debate, a shout was heard from the gallery that now was the time to blow up the place. A stampede was made from the House, confusion reigned for a time, till at last the police calmed the excitement by announcing that they had captured the interrupter, who turned out to be a drunken Dublin lawyer. When the union was carried the boroughs of Clogher and Augher were suppressed, but Abercorn pocketed £15,000 for Augher and the bishop of Clogher was on the point of securing a similar sum for Clogher.

With the modern history of Clogher I shall not deal at length on the present occasion, as I have already detained you too long, but I shall content myself with a mere reference to three distinguished children of the parish in recent times – I mean CARLETON, Rose KAVANAGH and Archbishop HUGHES.

CARLETON tells us himself, that he was born at Prillisk, in 1794. His youth was spent in different portions of the parish of Cogher. He gives an interesting account of the schools which he attended, especially at Findramore and Kilnahushogue, and on the estate of education in this district, at his time. He wonders why the strong Presbyterian farmers of Aghentaine did not take some steps to provide a suitable education for their children, but if I might suggest it, I would say that if it were left to themselves, the strong famers of Aughentaine would not have provided a school till the present day. It is also passing (?) strange that the Protestant bishop of Clogher, who in the plantation period had got 200 acres of land to provide a school, did not take some steps to ensure that the trust was seriously carried out.

He gives us an interesting account of the state of the Catholics in his day. He says they were completely at the mercy of the Orange magistrates and Grand Jury men. In his day there was no catholic house of worship in the district. At three places in the parish, corresponding to the Firth, Eskra and Aughentaine, the people assembled on Sunday and knelt around on the green, while the priest said mass in an open shed. But it is noteworthy that even then there was a good choir in the Forth.

CARLETON was intended for the Church and having abandoned that, he was a good-for-nothing, or treated as such, by his relatives. He went to visit two priests, his relatives, one of them about Killanny, the other keeping a school at Dundalk. The latter of these was very delicate and very nervous about death. When CARLETON was on his way to Dundalk he accepted the offer of a seat in a hearse kindly offered him by the driver and it was in this conveyance he arrived at the door of his friend’s residence. The poor priest was standing at his window and imagine his surprise and terror when in the dusk of the evening, he saw a hearse stopping before the house and his worthy cousin descending. This incident settled all chances of assistance in that quarter. CARLETON visited many places before he finally settled in Dublin. He changed his religion, he made a name in literature, he received a Government pension and yet, he was far from being happy. The scenes of other days constantly arose before his view and his state of feeling is beautifully described in one of his poems, Knockmany, which I shall quote for you.

A sigh for knockmany

Take proud ambition, take thy fill

Of pleasures won through toil or crime,

Go. learning, climb thy rugged hill

And give thy name to future time.

Philosophy be keen to see

Whate’er is just, or false, or vain.

Take each thy meed, but oh! give me

To range my mountain glens again.

Pure was the breeze that fanned my cheek

As o’er Knockmany’s brow I went;

When every lonely dell could speak

In airy music vision-sent.

False world, I hate thy cares and thee,

I hate the treacherous haunts of men;

Give back my early heart to me,

Give back to me my mountain glen.

How light my youthful visions shone.

When spanned by fancy’s radiant form!

But now her glittering bow is gone.

And leaves me but the cloud and storm;

With wasted form, and cheek all pale –

With heart long seared by grief and pain;

Dunroe I’ll seek thy native gale,

And tread my mountain glens again.

Thy breeze once more may fan my blood

The valleys all are lovely still:

And I may stand as once I stood,

In lonely musings on thy hill.

But ah ! the spell is gone – no art

In crowded town or native plain.

Can teach a crushed and breaking heart

To pipe the song of youth again.

Rose KAVANAGH, one of the most gifted of our modern Irish writers was born at Killadroy Co. Tyrone, in the year 1860. She was educated at the Loreto Convent school in Omagh and from Omagh she went to the School of Art in Dublin. But like many others, she soon deserted art for literature and was soon an honoured contributor to many of the leading Irish magazines and papers. She was greatly liked in Dublin for her jovial, happy and innocent disposition. On one occasion it is said that an old farmer who wished to post a registered letter in Dublin and who did not know where to put it, accosted her as she walked along the street. He told her that he could not trust the people he saw around him, but that he knew she had an honest face and would give him an honest advice. Nor was he mistaken.

For years she conducted, with signal success, the “Uncle Remus” column, at first in the ‘lrish Fireside” and afterwards in the pages of the “Weekly Freeman.” She was a constant contributor to the “Irish Monthly” and no contributor was more valued by its good-natured and energetic editor, Father Matthew RUSSELL. But unfortunately for Ireland and for literature, consumption had marked Rose KAVANAGH for its own. A journey to the South of France was unavailing. She returned to Mullaghmore, where she died in 1890. She was buried in the graveyard by the Forth, the place that she herself preferred. I shall quote for you only one of her poem, the verses on Knockmany, published in the “Irish Monthly” of 1884

Knockmany By Rose KAVANAGH

Knockmany, my darling I see you again,

As the sunrise has made you a King;

And your proud face looks tenderly down on the plain

Where my young larks are learning to sing.

At your feet lies our vale, but sure that’s no disgrace;

If your arms had their will, they would cover

Every inch of the ground, from Dunroe to Millrace,

With the sweet silent care of a lover.

To that green heart of yours, have I stolen my way

With my first joy and pain and misgiving.

Dear Mountain! old friend, ah! I would that to day

You could thus share the life I am living.

For one draught of your breath would flow into my heart,

Like the rain to the thirsty green corn;

And I know ‘neath your smile all my cares would depart

As the night shadows flee from the morn.

The last person from the parish to whom I shall briefly refer is Archbishop HUGHES. He was born in the parish of Clogher in the year 1797, the worst year for the Catholics of Tyrone and Armagh. It was then that the Orangemen committed the depredations for which the order shall be ever notorious. His father was a farmer and the future Archbishop was employed first on his father’s farm and afterwards, as a gardener, in MOUTRAY’S of Favour Royal. His father emigrated to America and young HUGHES followed him there. In America he wished to become a priest, but he had no money to pursue his studies. He was received at last into Mount St. Mary’s on condition that in return for his education, he looked after the college garden. On his ordination as a priest he worked with such energy and zeal, that in the year 1854 he was selected as coadjutor Archbishop of New York. The diocese was then in a very unsettled state, but the young Archbishop soon dealt with the “Trustee” trouble and set matters right in New York. In the “School question” and in the struggle against the intolerance of the “Native American” party, he took a prominent part. The “Native American” party in their hatred of the Irish and the Catholics had burned the churches and convents of Philadelphia. They threatened to do the same in New York, but the Archbishop marshalled his forces, prepared to resist violence and when the city authorities learned of his resolve, they took measures to prevent the disturbance. During the civil war of America he travelled Europe, visiting all the courts, as the agent of the Northern State and endeavouring to prevent the idea of interference from Europe. But in all his struggles he never forgot that he was an Irishman. His voice and his pen were always at the service of his countrymen.