Compiled and transcribed by Teena from the noted resources.

History of All-Hallow-Eve

All-Hallow-Eve is now, in our country towns, a time of careless frolic and of great bonfires, which I hear are still kindled on the hill-tops in some places. We also find these fires in England, Scotland, and Ireland, and from their history, we learn the meaning of our celebration. Some of you may know that the early inhabitants of Great Britain, Ireland, and parts of France, were known as Celts, and that their religion was directed by strange priests called Druids.

Three times in the year, on the 1st of May for the sowing; at the solstice; June 21st for the ripening and turn of the year; and on the eve of November 1st, for the harvesting; those mysterious priests of the Celts, the Druids, built fires on the hill-tops in France, Britain, and Ireland, in honor of the sun. At this last festival the Druids, of all the region, gathered in their white robes around the stone altar, or ‘cairn’ on the hill-top. Here stood an emblem of the sun and on the cairn was the sacred fire, which had been kept burning through the year.

The Druids formed about the fire and at a signal, quenched it, while deep silence rested on the mountains and valleys. Then the new fire gleamed on the cairn, the people in the valley raised a joyous shout, and from hill-top to hill-top, other fires answered the sacred flame. On this night all hearth fires in the region had been put out, and they were rekindled with brands from the sacred fire, which was believed to guard the households through the year.

But the Druids disappeared from their sacred places, the cairns on the hill-tops became the monuments of a dead religion, and Christianity spread to the barbarous inhabitants of France, and the British Islands. Yet, the people still clung to their old customs and felt much of the old awe for them. Still they built their fires on the first of May at the solstice, in June, and on the eve of November First. The church found that it could not, all at once, separate the people from their old ways, so it gradually turned these ways to its own use, and the harvest festival of the Druids, became in the Catholic Calendar, the Eve of All Saints, for that is the meaning of the name. All-Hallow-Eve. In the 7th century, the Pantheon, the ancient Roman temple of all the gods, was consecrated anew to the worship of the Virgin and of all holy martyrs. The festival of the consecration was held at first on May 13th, but it was afterward changed to November 1st, and thus All Saints Day as it is now called, was brought into connection with the Druid festival. This union of a holy day of the church, with pagan customs, gave new meaning to the heathen rites in the minds of the common people, and the fires which once were built in honor of the sun, they came to think were kindled to lighten Christian souls, out of purgatory. At All-Hallow-Tide the church bells of England used to ring for all Christian souls until Henry VIII and Elizabeth forbade the practice.

But by its separation from the solemn character of the Druid festival, All-Hallow-Eve lost much of its ancient dignity, and became the carnival night of the year for wild grotesque rites. As century, after century passed by, it came to be spoken of as the time when the magic powers, with which the peasantry all the world over, filled the wastes and ruins were supposed to swarm abroad to help, or injure men. It was the time when those first dwellers in every land, the fairies, were said to come out from their grots and lurking places, and in the darkness of the forests, and the shadows of old ruins, witches and goblins gathered. In course of time the hallowing fire came to be considered a protection against these malicious powers. It was a custom in the 17th century for the master of a family, to carry a lighted torch of straw around his fields, to protect them from evil influence through the year, and as he went he chanted an invocation to the fire.

Because the magic powers were thought to be so near at that season, All-Hallow-Eve was the best time of the year for the practice of magic, and so, the customs of the night grew into all kinds of simple, pleasant divination, by which it was pretended that the swarming spirits gave knowledge of the future. Even nowadays it is the time especially of young lovers, divinations, and also for the practice of curious and superstitious rites. And almost all of these, if traced to their sources lead us back to that dim past out of which comes so much of our superstition and fable.

But belief in magic is passing away, and the customs of All-Hallow-Eve have arrived at the last stage; for they have become mere sports, repeated from year to year, like holiday celebrations. Indeed, the chief thing which this paper seeks to impress upon your minds, in connection with All-Hallow-Eve, is that its curious customs show how no generation of men is altogether separated from earlier generations. Far as we think we are from our uncivilized ancestors, much of what they did and thought, has come into our doing and thinking, – with many changes perhaps, under different religious forms and sometimes, in jest where they were in earnest. Still, these customs and observances (of which All-Hallow-Eve is only one) may be called the piers, upon which rests a bridge that spans the wide past between us and the generations that have gone before. (St. Nicholas, conducted by M.M. Dodge, Vol. 9 1882)

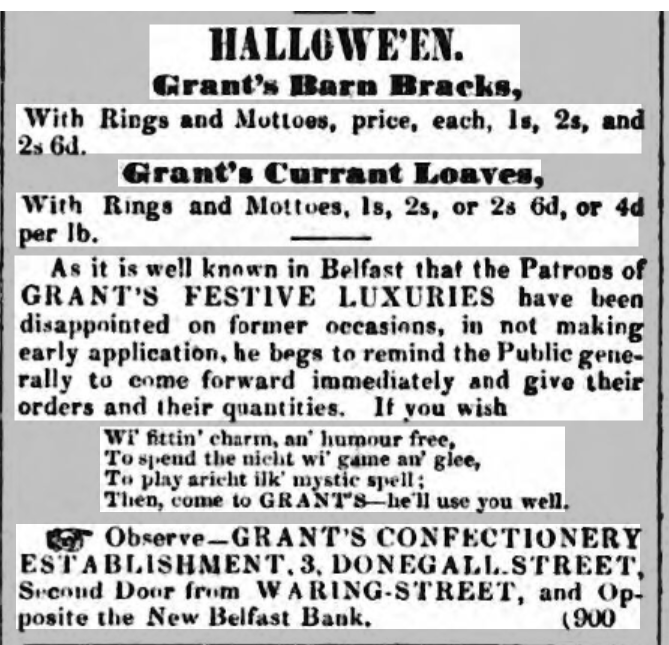

30 Oct. 1838 HALLOW’EN CAKES

We invite attention to the advertisement of Mr. GRANT, relative to his “Hallowe’en Cakes” which, at this season of established hilarity, are an indispensable requisite in every domestic circle. The high character of Mr. GRANT and the celebrity which his establishment has so justly gained, are sufficient guarantees as to quality and for cheapness; it is impossible to imagine anything more so. In order to prevent disappointment, as the demand cannot fail to be extensive, he has opened for the occasion a shop in Corn-market, as an auxiliary to his Establishment in Donegall-street. (Belfast Newsletter)

31 Oct. 1838 Hallowe’en Cakes

Mr. James GRANT is the only person in Belfast who prepares these cakes; and for the convenience of his friends, has opened shops at 49 Donegall street and 6 Corn-market. How our juvenile friends will stare, when they find Mr. GRANT having prepared for their festivities, no less than 6,000 cakes! (Belfast Newsletter)

7 Nov. 1845 – Turnip Lanterns

The little ones excavating away with gully knives at their turnip lanterns and advising with their seniors, what kind of face to make on it, that will be most fearsome (Tyrone Constitution)

30 Oct. 1846 – The vigil of All Saints

The anniversary of Halloween – the vigil of “All Saints” – (31st October) – is one of the most cherished and observed of our popular festivals; it is ‘kept’ as is the expression, of all classes and denominations, throughout Ireland – more especially in Ulster, Scotland, and the north of England, while traces of it, more or less obvious, are to be perceived in every part of Great Britain. A quaint writer observes: “The vigil of All Saints is a “spiritual” anniversary, when superstition, which is the child of ignorance, impiously snatches the dark veil of futurity, and love-sick visions mingle abroad. There exist a supernatural and unhealthy craving in the mind, as the body, for things which are destructive to the human system. We diet upon sound, and death is the compass of our knowledge. All the rest is an “ashen apple”. We do not coincide with the notion that the anniversary is of spiritual (religious) origin, but conceive that the peculiar character of the observances and superstitions clearly assign it those “Pagan” rites, by which, before the appearance of christianity, mankind attempted to pry into the mysteries of the future, especially those that most deeply affect the sympathies of our nature, and which, as in so many other instances, the Catholic church has adopted among her own multitudinous observances, with the design of diverting the popular mind from the old superstitions, and as, from the number of saints in the calendar, a particular day could not be set apart in honour of each,

“All Saint’s Day” was appointed, that due respect should not be omitted to any. In the year 731, Pope Boniface IV. dedicated to the Virgin,”metor omnium sanctorum, the Pantheon at Rome. Notwithstanding, even yet, there are unequivocal remains of the heathen ceremonies.

Be it as it may, the season is one of the most hearty enjoyment, occurring at a time when, generally, the harvest has been safely gathered in, and plenty smiles securely upon the toil-worn husbandman, is hailed with delight, and all that ‘social glee’, which everywhere crowns the hearth, and gives “character” to the Irishman’s meanest home. It were impossible, within the compass of a short article, to give anything like an account of the different modes by which, on this night, it is attempted to divine what fate has in reversion, in the shape of wife or husband, for each longing bachelor or maid.

There is the burning of nuts; the pulling of cabbage stalks, strait or crooked; the pouring of molten lead through the handles of door keys; the unwinding of yarn from a clew thrown into a kiln pot; the washing of shirt sleeves in streams running due south, to be hung dry at midnight by the kitchen fire, while from bed the form of an expected husband or wife is waited for in fear and trembling; then there is the drawing of corn stalks; the sowing of hemp seed; and the eating an apple before the looking-glass, &c. with the innumerable spells by which the destined form is to be evoked from the world of shadows. Then we have the trolies, of the youngsters: the “stoving” of some asthmatic neighbour’s house; the splashing and sputtering in the water-tub, in a vain attempt to catch the evasive apple; and, most sportive of all, the critical endeavour to catch an apple, with teeth alone, as, with a candle placed on the same stick, it rapidly revolves, and the adventurous urchin full oft retires with face scorched, and besmirched with grease, instead of having caught the tempting fruit.

The peculiar characteristic of the festival, however, is the prevailing opinion that, on this night, witches, fairies, sprites, and all sorts of supernatural beings, have full scope, and are abroad on their malignant errands.

Now the peasant’s wife devoutly crosses herself and turns an anxious eye to the cradle of her child, lest it should become a “changeling”, as in the rattling blast she fancies she can hear a troop of witches hurrying by on mounted broom-sticks or bin-weeds, or an army of fairies galloping along on their tiny steeds.

Mr. GRAYDON, a countryman of ours, thus alludes, in his poem to the Halloween nut burning

These glowing nuts are emblems true,

of what in human life we view;

The ill-matched couple fret and fume.

And thus in strife themselves consume

Or from each other wiblly start,

And with a noise for ever part;

But see the happy, happy pair.

Of genuine love and truth sincere.

With mutual fondness, while they burn,

Still to each other kindly turn,

And as the vital sparks decay,

Together gently sink away,

Still, life’s fierce ordeal being past.

Their mingled ashes rest at last.

(Tyrone Constitution)

1 Dec. 1849 – Love Tests of Halloween

The eve of All Saints’ Day is memorable, as a time when the fairies hold a grand anniversary, and when witches and evil beings are abroad on errands of mischief. This superstition, modified in various ways, finds a place among the peasantry of other nations. Halloween used to be observed by country maidens as a time for trying sweethearts, and gaining such an intelligible peep into futurity as would enable them to find out whether they would be married or not; and, if that happy event was to crown their lives, who would be the man of their choice. And even at this time, “Halloweve,” as it is called, is not suffered to come and go without the effort of some loving maidens to penetrate the mystery of their matrimonial future. The modes of trying sweethearts, and the various love-tests applied, are curious enough; burning nuts, the love-candle, eating an apple before the looking-glass at midnight, the salt egg, and dropping melted lead through a key into a basin of water, are a few of them, and all must be accompanied by particular ceremonies or incantations, in order that they may have the desired power to lift the veil of futurity. (Newry Telegraph)

4 Nov. 1864 – Belfast Police Court – ‘Nainsel Frae the Heelans’ she came.’

John M’APPIN, a “bonny braw John Heelan man,” was taking his Hallowe’en spree about the Queen’s Quay Tuesday night. A lady was coming along, with a bandbox in her hand, and John took it into his head to run against her, and crush the box up against the wall. Unfortunately for the experimenter, Mr. MAGEE was looking after the welfare of the lieges in that quarter, and saw the operation. He cautioned Mr. M’APPIN, but that gentleman only grew noisy, and the result was his introduction to Mr. O’DONEL. Mr. YOUNG reminded his worship that allowance ought to be made for Hallowe’en. But Mr. O’DONEL did not think that particular day was entitled to the license of a saturnalia, and fined the defendant 5s. (Tyrone Constitution)

8 Nov. 1879 – All Hallow Eve in Ireland

Illustrative of some of the popular superstitions pertaining to the time.

On Hallowmas Eve, ere ye’ve gonne to reste,

Ever bewaire thatte yr couche be blessede

Sign itte wythe cross, and sain itte wythe beade,

Sing the Ave, and saye the Crede.

Though Bonnie Scotland bears away the bells from all other countries for strict observance of the charms and superstitions of “Snap Apple Night,” yet the rites and witcheries peculiar to that festive occasion being somewhat similar in Green Erin, – I trust I may be pardoned- as the season is here with us, if I make essay to give my English readers some faint idea of the spells and incantations, clearly ancient Druidical memorials, as well as the sports and pastimes, that, on this witching Eve, make bright many a farmer’s fireside on the other side the “silver strip of sea.”

Supper being done and the utensils cleared away in the kitchen of some strong farmer’s house, the hearth is cleanly swept over, and the turf sods piled high on the fire, until it assumes almost gigantic dimensions; then one by one the neighbours come dropping in with a cheery “God save all here” from the older folk, and a merry nod, or sly bantering remark, from the younger until at last quite a goodly company is assembled. The ‘vanithee’, or good woman of the house, now rising from her seat and being dressed in Sunday attire for the occasion, retires for a moment to what is termed an upper room, though still on the ground floor of the building, and returns, accompanied by one of the maids, bearing between them an enormous skeed, or sieve of rosy-cheeked apples while some other female member of the family lifts in a crock of nuts, brown and beautiful, as nuts should ever appear at such seasonable time. These at first being handed around ceremoniously amongst the visitors, and a brew of good whisky punch circulated by the hands of the farmer himself through the elders, who generally sit coshering by the fire, the evening’s sports may be said to commence, when some tall, strapping young fellow at the far end of the apartment affixes, by means of a string to one of the collar beams a rude horizontal cross of wattle, sharpened at the ends and bearing on its alternate points plump, jolly-looking apples, and bits of lighted candle-ends. This apparatus being hung about breast high, it is set swinging around, and then the champions enter the lists beneath the admiring eyes of their sweethearts. A great, hulking farm youth, with health glowing in every feature, setting his hands on his knees, and stooping low, bites at the apple as it swings whirling past his laughing teeth, but, alas! for him, his laughter is soon changed to a shriek of pain, when he catches, instead of the juicy apple, within the cavity of his mouth a noisome and burning candle-butt; while the lookers-on almost scream with mirth at his misfortune.

But the attention of the spectators is soon drawn away from here, for in the centre of another little knot a lump of a “boy” has placed a rush-bottomed chair, back upwards, and kneeling thereon, divested of his coatamore, he essays to snatch with his mouth an apple placed on the extreme end in a tempting, but treacherous position for, alack and well-a-day, this feat ever ends by the chair tilting over, and the luckless performer coming prone on his nose to the hard earthen floor beneath, his disaster being always the signal for another uproarious guffaw. This trick is oftentimes made more risky by a pail of water being placed immediately beneath the chair end whereon lies the apple.

Another favourite sport of the night is what is termed diving for apples. A large tub, filled to the brim with water, is placed on chairs in the centre of the kitchen, and a couple of luscious looking apples are set afloat within. Then some adventurous “gossoon” making bare his neck and chest, and placing his hands behind him, stoops laughing over, and bobs open-mouthed at the tempting fruit so near. but this, like Will o’ the Wisp of the fable, ever evading him, he generally winds up by toppling over into the tub, whence he arises like a river god, dripping and miserable but yet with chattering teeth endeavouring to keep up the illusion that he too is enjoying the sport to which he has so sheepishly contributed. This feat is made still more tempting to some of the impecunious of the guests by placing a shilling, or a sixpence, at the bottom of the tub, which coin is seldom if ever lifted by the diver.

And now the fun goes fast and furious. Perhaps a stray fiddler may have chanced to come the way, and, if so, then hurroo! for the light heart and the light heels. Then, while all eyes are otherwise engaged, some meek-eyed maiden will slip quietly to the fire, and taking two nuts from her bosom, will, secretly naming one after the lad of her choice and the other after herself, set them together in the red embers. If they burn gently out it denotes the courtship will have a happy termination, but if one of them, or both start violently away, anything but matrimony will be the ending of the acquaintanceship and, preposterous as it may seem, many a gentle girl that, like Shakespeare’s heroine,

never told her love,

But let concealment, like a worm i’ the bud,

Feed on her damask cheek,

has gone to her home half broken-hearted from the result of her night’s nut-burning.

Close by the fire too, and superintended by some garrulous crone, there can always be seen an anxious circle who endeavour to snatch some of the secrets of destiny by pouring molten lead through the ring of a door key into a tub or basin of water, then whatever fantastic shape the lead assumes in cooling is read forth by the beldame, and listened to and accepted as the teachings of a sibyl. Or, perhaps, the same old dame stands directing the awful charm, worked by four plates being placed on a table one containing clay, one a ring, one water, and one salt. To this the aspirant is led blindfold, when, putting forth his or her hand, if it meets the clay it denotes speedy death and the grave; if the ring, marriage with a widow or widower; if salt, future wealth; and if water, that the marriage will be with someone connected with the sea.

While these are in full blast, others of the girls, after whispering together, steal out unperceived to cut cabbages, the stalk of which, being crooked or straight, denotes the beauty, or ugliness of the future husband or wife; or they go- but “this must be done alone and at the witching hour of midnight to the nearest churchyard, or, if no churchyard be within range then to the nearest lime-kiln, and tossing a ball of worsted over, begin winding it in until some one catches the end; then is asked, “Who holds”? And the one allotted as husband or wife answers in their own recognised voice. (This is one of the most awful of the charms, and has led in many instances to death or madness. That poetical dramatist, Mr. W. G. Wills has introduced it into one of his plays, where it proved most effective). Or they go to a running stream, where three townlands meet, and dipping the left sleeve of the innermost garment three times, return home and hang the article to dry, when the future husband or wife will come and turn the sleeve at the fire.

There is another lonely charm, called eating the apple at the glass. It is worked thus; you go all alone to some room where there is a looking-glass, and, setting down the light, you comb out your hair with one hand; while eating an apple from the other; the one decreed to you by fate looks over your shoulders while you eat, or you can bring him or her more readily to your side; by throwing the peel of the apple in strips over your shoulders, whispering the magic name three distinct times.

By taking three handfuls of rye, and, stealing out alone, sowing it over the nearest ploughed land, against the wind, then calling your true love as many times as you have handfuls of the corn, you will perceive him, or her, coming after you and in the act of reaping.

The last of the lonely charms of which I have knowledge is going out into the hay-yard, and quite unperceived fathoming with your arms the first com stack you find, when, at the third fathoming, you will grasp in your arms the form of the one you love; but you must be very careful, as it is in this feat the malignity of the Phooka is oftenest experienced, and this is the night he is known to appear in all the devilry of his glory.

Whether the Phooka appears to you as a horse or a bull, for he takes both shapes, his great object is to get you for a rider. This he best achieves at the fathoming of the stack. Then woe betide you, for he takes you over precipices, rivers, rocks, seas, all are alike to him and heedless of your cries, and only guided by his own wicked will, he sets you down only when his malevolence is satisfied; a being ruined and broken in health and spirits, and doomed only to mope out as a maniac, the short remnant of your days.

And now comes the witching time for dreaming, when the guests having taken their final departure. All the foul water in the house being cast outside the door, the maids seek their pillows to dream, and to dream only, and this they secure by the aid of the all-powerful ivy leaves, and yarrow, which they take with them, to place beneath their heads, muttering the incantation as they lie to rest –

Good-morrow, good-yarrow, good-morrow to thee,

Tell me by to-morrow, whom my true love’s to be.

Let him come to me in the land of dreams,

Such as just now on the earth, he seems.

Let me see him and know his voice that I,

May learn if I am to smile, or to sigh.

Godspeed ye, good-yarrow, till morning’s first beams,

Now, lover, light lover, oh come to my dreams.

And so ends the witching night of Hallowmas, or so it ever used to end in dear old Ireland. by M. F. (Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News)

1883

The ‘Holy Eve’ in Dublin, as far as customs are kept up, is only a semblance, or shadow, of what it was in the early years of the present century. (1883) For a number of years past many families content themselves with buying a few apples and nuts and taking a hot ‘jorum’, perhaps of John Jameson’s seven year old, if they are not teetotallers and can afford it. When we were boys even in Anglo Saxon Dublin, numbers of the working classes and others would be seen, accompanied by some of their children, making their way to the Little Green or Fruit Market to buy their supply of apples and nuts for Holy Eve. Those visits were often postponed till the very night in question, when the market would be lit up with any number of candles and barrels of apples and nuts were made to present an enticing appearance. Some folk went to the Fruit Market on Holy Eve merely to see the sight. The evening or night was observed by the people in their homes by a number of customs on the part of young and old, of both sexes, such as diving for apples in tubs of water, or striving to bite an apple off a suspended revolving hoop, with lighted candles, and apples fixed alternately round its circumference. Then followed divinations, by placing grains of wheat, or nuts, on the bars of the grate and associating certain couples with them. If the two grains of wheat, or the nuts, stuck fast on the bar and burned there, it was a happy augury for the union of a certain pair, but if one of the nuts or grains of wheat hopped off the bar, there was no hope for Paddy, and Biddy, or Mike, and coming together.

Pieces of lead were also melted in a ladle, or big spoon, the key taken out of the door, and the molten liquid poured into the water, through the ring of the key. A number of fantastic shapes of course, resulted, and the old crones called upon to divine what was likely to result, and what the shapes represented. A wedding carriage was sure to be conjured up, and other equally pleasant objects to some young couple. The custom of eating apples and cracking nuts may continue for long years, but we fear, the keeping of Halloween on the old lines, is doomed to disappear shortly, like many other of old native customs, which though once rife among the Gael, are now extinct. (Irish Builder and Engineer, Vol. 25)

1886

Hereabouts the people say that if a babby be born on this night it rins’ a moighty good chance o’ bein’ possessed by some sproite or other, it may or may not be true oi’m sure it’s beyont the likes o’ me to say whether soch things are possible or not.

It’s the custom in these parts for the childer to run into the cabbage yard ‘afore the evenin’ fun begins, an’ to pick out a number o’ cabbage stalks, an name them arter any seven o’ the folk they have annything to do with; then having finished wi’ this choosin’, they dance round the place shouting out,

One, two, three, an’ up to seven

If all are white, all go to heaven

If one is black, as Murtagh’s evil

He’ll soon be screechin’ wi’ the devil.

awl’ the childer’ havin’ finished their song, ran into the house an asked all the folk to come out an’ see their sowls.’

The dairy maids and farm servants engage in moulding something with their hands. They’re going through the ‘dumb cake ceremony’, which consists in their kneading with their ‘left thumbs’ a piece of cake, without uttering a single word. If one of them intentionally, or accidentally, should breathe a single syllable, the charm would be broken, and not one of them would have her burning hopes of seeing her future husband in her dreams fulfilled. Their dumb cake ceremony long over and they now busily engage in finding out the state of life to which their respective future lovers belonged. To gain this interesting information, it was necessary that molten lead should be poured into cold spring water. According to the fanciful shapes the lead took, as each small quantity was poured out, so each girl framed her fancy, now, something like a horse would cause the jubilant maiden to call out “A dragoon”! some dim resemblance to a helmet would suggest a handsome member of the mounted police, or a round object with a spike would seem a ship and this, of course, meant a sailor, or a cow would suggest a cattle dealer; or a plough, a farmer, and so forth. Great amusement can be got from the rite and in some cases caused by laughter and blushing denials, guesses seem to be based on something more substantial than mere fancy.

Children play the game of ‘snap apple’; the dipping for apples; high up among the dusky rafters, wherefrom hung flitches of bacon, ox tongues, onions, and other articles of strange hue, and shape, one would fasten a piece of strong cord, suspended at the lower end of this, within a few feet from the ground was a short skewer, gripped about midway by the knot of the string, and at either end of the skewer, was respectively a tempting ruddy apple and a lighted tallow candle. As soon as the cord was set in motion the game began.

A young boy, carefully watching for his opportunity, as the cord swung back, from right to left, sprang like an arrow, but was just a moment too soon, for he hit the candle with his face and sent it spinning to the floor. His locks were well-singed and a goodly splotch of tallow lay on his perky nose, but he laughed as heartily as the others and seemed in no wise put out at his discomfiture. With varying adventures the different children all had their chances, no-one however, to the general merriment proving successful, till at last a young lad’s turn came round again. This time his sharp white teeth grabbed the coveted prize and he retired from the game, another equally tempting apple being put in the last one’s place. When another child’s turn came, he quietly slid under the swinging cord, waited for its backward motion from left to right and then meeting the apple full face secured it with ease. It was said of this child “He’s a cautious yin’, he is, he war’ determeened that if he didna’ grab the apple, he wud, at enny rate, mak sicker o’ no’ bein’ singed wi’ the cawnle.”

A crowning delight was the “Halloween jig”. This was a custom in which every one joined and there was nothing short of ecstasy in the tumult of stamping feet, snapping fingers, happy laughter, which mingled with the wild music of the pipes. (Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Vol. 73 in 1886)