Typhus Fever & Famine in Ireland 1817-18, with a particular focus on the County of Tyrone, but not limited to.

Dr. Gerard BOATE, in his Natural History of Ireland, published in 1652 enumerates amongst the diseases to Ireland is “peculiarly obnoxious”, “a certain sort of malignant fevers, vulgarly called Irish agues, because they are at all times so common in Ireland.”

The symptoms, by which he characterizes this species of Fever, leave no doubt that the disease is the same with that, for the prevention and cure of which, Fever Hospitals have in our days been erected. It is not a little remarkable that establishments of this kind were first founded in Ireland. The Fever of 1801 does not appear to have been epidemic throughout the whole island; its greatest prevalence was confined to the southern provinces and according to accounts, would seem to have been in a great degree, propagated from the county of Wexford.

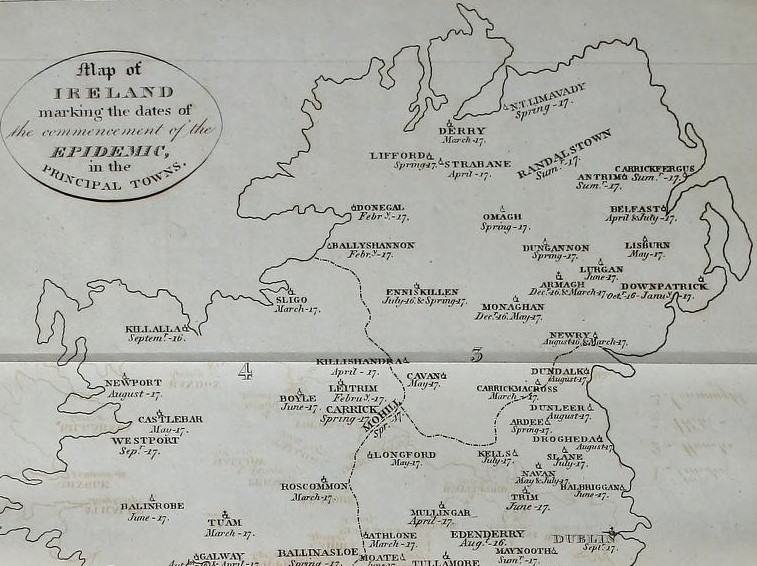

From the above map it may be collected that Fever was more than usually prevalent in various and distant parts of Ireland so early as the autumn and winter of 1816. In Ulster, Fever is found at Enniskillen in July; at Newry in August; at Downpatrick in October; and at Monaghan and Armagh in December. The progress and duration of the disease were very variable. In some places it advanced with a rapid pace to its height and then steadily subsided; in other quarters it was slower in its progress and more fluctuating in its course, breaking out with renewed vigor, after having been, to all appearance, subdued; its fatality also was in a great degree proportioned to its rapidity. Thus in the province of Ulster and in some of the counties bordering on it, the Epidemic was both, more fatal and rapid in its duration, than in the other provinces. It was most prevalent and fatal in the autumn and winter of 1817.

Contributing Factors to the Famine- Increased Population & the Failure of the Potato Crop

In a passage quoted by T. R. Malthus’s ‘Essay on the Principle of Population’, he showed how disastrous a failure of the crop must be, when the staple was potatoes the people then had nothing between them and starvation, but the garbage of the fields. What the growth of population could come to on these terms was carefully shown for the district of Strabane on the borders of Tyrone and Donegal by Dr. Francis ROGAN, a writer on the famine and epidemic fever of 1817-18. (Dr.’s SWEENEY and KILDARE were also of Co. Tyrone)

Strabane stood at the meeting of the rivers Mourne and Fin, to form the Foyle and in the 3 valleys, the land was fertile. All around was an amphitheatre of hills, in the glens of which and among the peat bogs on their sides, was an immense population. The farms were small from 10 to 30 acres; a farm of 50 acres being reckoned a large holding. The tendency had been to minute sub-divisions of the land; the sons dividing a farm among them on the death of the father.

“The Munterloney mountains”, says Dr. Rogan, “lie to the south and east of the Strabane dispensary district. They extend nearly 20 miles and contain in the numerous glens, by which they are intersected, so great a population, that except in the most favourable years, the produce of their farms is unequal to their support. In seasons of dearth, they procure a considerable part of their food from the more cultivated districts around them and this, as well as the payment of their rents, is accomplished by the sale of butter, black cattle and sheep and by the manufacture of linen cloth and yarn, which they carry on to a considerable extent.” These small farmers dwelt in thatched cottages of 3 or 4 rooms, in which they brought up large families. Besides the farmers, there were the cottiers who lived in cabins of the poorest construction, sometimes built against the sides of a peat cutting in the bog. The following table shows the proportion of cottiers to small farmers on certain manors of the Marquis of Abercorn in 1817-18.

The number of families within the following Manors;

Manor of Derrygoon – Farmers 368, Cottiers 335

Manor of Donelong – Farmers 243, Cottiers 322

Manor of Magevelin and Lismulmughray – Farmers 319, Cottiers 668

Part of Manor of Strabane – Farmers 302, Cottiers 415

Manor of Cloughognal <sic> – Farmers 328, Cottiers 279

The cottiers rented their cabins and potato gardens from the farmers, paying their rent on terms, not advantageous to themselves, by labour on the farm.

this cabin is located at Meenagarragh in the Parish of Bodoney Upper

At the date of the famine of 1817, there was sub-letting going on of which, Dr. Rogan gives an instructive instance in his district of Ulster.* Under this system of sub-dividing farms and sub-letting potato gardens with cabins to cottiers, the following enormous populations had sprung up in 4 parishes within the dispensary district of Strabane and in 4 manors of the Marquis of Abercorn adjoining them, but not included in the dispensary district. The dispensary district of Strabane contained a total population of 16,258;

Town of Strabane – 3896

Parish of Camus – 2384

Parish of Leck – 5092

Parish of Urney – 4886

On the Marquis of Abercorn’s estate, which is not within the dispensary bounds, contained a population of 14,038 persons;

Manor of Magevelin and Lismulmughray – 5548

Manor of Donelong – 3126

Manor of Derrygoon – 2568

Manor of part of Strabane – 2796

In the language of the end of the 19th century, this would have been called a congested district of Ireland; but all Ireland was then congested to within a million and a half of the utmost limit, so that the famine, which we shall now proceed to follow in this part of Ulster, has to be imagined as equally severe in the rest of Ireland.

*Dr. Rogan “A farmer within my knowledge, who holds 15 acres of arable land, with nearly an equal quantity of cut-out bog, for which he pays £28 per annum, has erected 6 cabins for labourers. They are built with mud, instead of lime and are thatched, so that they cannot each have cost more than 3 or 4 pounds. For some time he received from 3 of his tenants, 6 guineas per annum, and from the others, 2 guineas each, the latter only holding a cottage and a small garden, the former 3, having also grazing for a milch cow, half a rood of land for flax, and half an acre for oats, with privileges of cutting turf and planting as many potatoes as they could each provide manure for, but they have been all so reduced in circumstances by the late scarcity, as to be now unable to keep a cow and for the last 2 years have rented their cabins and potato gardens alone. All the straw raised on the farm would scarcely suffice to keep the houses water-fast, if applied solely to this purpose. One of the first things that the Marquis of Abercorn did in the epidemic of 1817, was to call upon the sub-letting farmers on his manors to repair the roofs of their cottiers cabins.

The winter of 1815-16, had been unusually prolonged so that the sowing and planting of 1816 were late. They were hardly over, when a rainy summer began that amounted to 142 wet days (and these principally in the summer and autumn months), which led to a ruined harvest. The oats never filled and were given as green fodder to the cattle, in wheat growing districts the grain sprouted in the sheaf, the potatoes were a poor yield and watery, such of them as came to the starch manufacturers, were found to contain much less starch than usual. The peat bogs were so wet that the usual quantity of turf for fuel was not secured. This failure of the harvest came at a critical time. The Peace of Paris in 1815, had depressed prices and wages and thrown commerce into confusion. During the booming period of war, prices from 1803 to 1815, farms and small holdings had doubled, or even trebled in rent and had yielded a handsome profit to the farmers and steady work to the labourers. When the extra-ordinary war expenditure stopped, this factitious prosperity came to a sudden end. The sons of Irish cottiers were not wanted for the war and the daughters were no longer profitable as flax spinners to the small farmers. Weavers could hardly earn more than three-pence a day and labourers, who could find employment at all, had to be content with four-pence, or six-pence, without their food. A stone of small watery potatoes cost ten-pence, but the value of cattle fell to one third, and butter brought little. By Christmas, the produce of the peasants harvest of 1816, was mostly consumed. Many hundred families holding small farms in the mountains of Tyrone, had been obliged to abandon their dwellings in the spring of 1817 and betake themselves to begging, as the only resource left to preserve their lives. (b)

(b) Probably their cattle had been impounded for rent and tithe. The author of the pamphlet ‘Lachrymae Hiherniae Dublin 1822’, a resident on the western coast says p 8., with reference to the seizures for rent and tithe, “Oh! what scenes of misery were exhibited in Ireland in this way during the years 1817-18 and 1819; by that time the people were left without cattle, after this, their potatoes and corn were seized and sold, and in some cases, their household furniture, even to their blankets. The hardness of landlords in general, is alleged by Dr. Rogan, with an exception in favour of the Marquis of Abercorn in his own district.

In parts of Ireland the seed potatoes were taken up and consumed. The people wandered about in search of nettles, wild mustard, cabbage stalks, and the like garbage, to stay their stomachs. “It was painful”, (says William CARLETON) “to see a number of people collected at one of the larger dairy farms waiting for the cattle to be blooded, (according to custom), so that they might take home some of the blood to eat, mixed with a little oatmeal” The want of fuel caused the pot to be set aside, windows and crevices to be stopped, washing of clothes and persons to cease, and the inmates of a cabin to huddle together for warmth. This was far from being the normal state of the cottages, or even of the cabins, but cold and hunger made their inmates apathetic. Admitted later to the hospitals for fever, they were found bronzed with dirt, their hair full of vermin, their ragged clothes so foul and rotten that it was more economical to destroy them and replace them, than to clean them. Some months passed before this state of things produced fever. The first effect of the bad food through the winter, such as watery potatoes, eaten half-cooked for want of fuel, had been dysentery, which became common in February and was aggravated by the cold, in and out of doors. It was confined to the very poorest and was not contagious, attacking perhaps 1 or 2 only in a large family. Comparatively few of those who were attacked by it in the country places came to the Strabane Dispensary, but the dropsy, which often attended, or followed it, brought in a larger number.

The following table of cases at the Strabane dispensary shows, clearly enough, that dysentery and dropsy preceded the fever, which became at length, the chief epidemic malady. As may be seen from the following, the number of cases of typhus in a 4 month period of time, rose from 10 to 287 cases.

June 1817 – dropsy 23; dysentery 2; Typhus 10

July 1817 – dropsy 107; dysentery 31; Typhus 60

August 1817 – dropsy 40; dysentery 22; Typhus 106

September 1817 – dropsy 9; dysentery 23; Typhus 287

Dr. Rogan gives 2 instances from the Strabane district in the summer and winter of 1815, at a time when the district was remarkably healthy. A beggar boy was given a night’s lodging by a cottier at Artigarvan, 3 miles from Strabane. Next morning he was too ill to leave, he lay three weeks in typhus and gave the disease to 27 persons, in the 8 cabins, which formed the hamlet. A few months after, about a mile from Strabane, a mother fell into typhus and was visited many times by her 2 married daughters and by others of her children at service in the neighbourhood. Nineteen cases were traced to this focus, but the actual number attacked was probably more than 3 times this, as the disease, once introduced into the town, spread so widely among the lower orders as to create general alarm and led to the establishment of the small fever ward attached to the dispensary. It was in April 1816 that this was done, 2 rooms each, with 4 beds having been provided at Strabane for fever cases, but at no time until the summer of 1817, were they all occupied at once.

The epidemic really began there in May 1817 in a large house, which had been occupied during the winter by a number of families from the mountains; they had brought no furniture with them, nor bedding, except their blankets and lay so close together, as to cover the floors. Each room was rented at a shilling a week, the tenant of a room making up his rent by taking in beggars at a penny a night. The floors and stairs were covered with the gathered filth of a whole winter; the straw bedding, never renewed, was thrown into a corner during the day, to be spread again at night. Every crevice was stopped to keep out the cold, the rain came in through the roof, the floors were damp, and the cellars of the house full of stagnant water turned putrid. Meanwhile, more than ¼ part of the families resident in Strabane, to the number of 1026 persons, were being fed from a soup-house opened early in the spring of 1817, while there were others equally destitute, but too proud to ask relief. The rumour of this charity soon brought crowds of people from the surrounding country, “with gaunt cheeks,” says CARLETON, “hollow eyes, tottering gait, and a look of painful abstraction from the unsatisfied craving for food.” In the crowd round the soup-shop, the timid girl, the modest mother, the decent farmer, scrambled, with as much turbulent solicitation and outcry, as if they had been trained since their very infancy to all the forms of impudent cant and imposture. These soup-shops were opened in all the Irish towns. At Strabane, some of the richer class lent money to procure supplies for sale, at cost price, of oatmeal, rice, and rye flour, the last being in much request in the form of loaves of black bread.

The fever, having begun among the houseful of vagrants above mentioned, made slow progress until June, when it spread through the town and in the autumn became a serious epidemic. Meantime, the soup-kitchen was closed, the supplies having ceased and the country people returned to their cabins, carrying the infection of typhus everywhere with them. By the middle of October 1817 the epidemic was general in the country around Strabane. In the year 1817, the reported number of cases of typhus at Strabane’s dispensary were 1,227 persons and for the year 1818, reported cases were reduced to 679 cases. The exact particulars from the dispensary district of Strabane, show clearly how famine in Ireland is related to fever. The epidemic of typhus was an indirect result of the famine and was due most of all to the vagrancy, which a famine was bound to produce in Ireland, in the absence of a Poor Law. “It was lamentable” said Peel in the House of Commons debate on 22 April 1818 “at least it was affecting that this contagion should have arisen from the open character and feelings of hospitality, for which the Irish character was so peculiarly remarkable.”

The concourse of people at the daily distributions of soup was another cause of spreading infection, many of them having come out of infected houses. Of such houses, the lodging-houses of the towns we have several particular instances. At Strabane there were 4 such, which sent 96 patients to the fever hospital in 18 months. The spread of the disease was much aided by the ordinary annual migration of harvest labourers. It was the custom every year for cottiers in Connaught to shut up their cabins after the potatoes were planted and to travel to the country round Dublin, in search of work at the hay and corn harvests, leaving their families to beg in the same way; there was an annual migration from Clare to Kilkenny; from Cavan, Longford, and Leitrim into Meath, and from Derry into Antrim, Down and Armagh. In the summer of 1817 some parishes of Derry were left with only 4 or 5 families. The keeper of the bridge at Toome over the Bann, counted more than 100 vagrants every day passing into Antrim, from the middle of May to the beginning of July, and the same might have been seen at the other bridge over the Bann, at Portglenone.

The influence of famine is equally powerful and characteristic; necessarily producing such crowding of the poor and such deficient ventilation of their dwellings, as seldom fail to excite. The moment a scarcity of food is felt, more especially, if accompanied by any deficiency of employment, the poor of the country, particularly where the wealthier population is scanty, rush towards the cities and towns in search of employment and of food; there they occupy the lowest description of lodgings, waste-houses, or the most wretched hovels; if unable to procure a sufficiency of food by their labour, or by begging, they pawn, or sell, their furniture and clothing, aggravating by this temporary relief, their future sufferings. Thus they are brought together in great numbers and crowded into filthy and unventilated abodes, unfit for human beings; the nakedness of the inmates compelling them in inclement seasons to lie huddled together for the sake of warmth and to exclude, by every means every possible, access of the external air. In this way it is, that famine and fever are so intimately connected; not indeed directly, but indirectly. In the same way though in a lesser degree, are Fever and want of employment related; for as famine presses on the whole pauper population of a country, so want of employment affects a portion of that population. As the spread of contagion came to be realized, the ordinary hospitality to vagrants ceased. Dr. Rogan was struck with the apathy, which at length. arose towards the sick, or dead relatives, even parents became callous at the death of their children, of whom many died from smallpox. “For some time,” he says, “it has been as difficult for a pauper bearing the symptoms of ill health to procure shelter for the night, as it was formerly rare to be refused it.”

Strabane

In Strabane, they extemporized a poor fund by voluntary contributions of £30 a month by means of which, 80 poor families were kept from begging in the streets. An abstract of returns of the dispensary district of Strabane, showing the numbers ill of fever, from the commencement of the epidemic in the summer of 1817, till the end of September 1818 and the mortality caused by the disease (Rogan p. 72)

Town of Strabane – ill of fever 639, dead 59

Parish of Camus – ill of fever 685, dead 61

Parish of Leck – ill of fever 1,462, dead 96

Parish of Urney – ill of fever 1,381, dead 86

For a total in the Strabane district of a ill of Fever 4,167, Dead 302.

A similar return for those parts of the Marquis of Abercorn’s estates, not within the Dispensary district, shows;

Manors

Magevelin and Lismulmughray – ill of fever 1,666, dead 101

Donelong – ill of fever – 1,217, dead 71

Derrygoon – ill of fever 1,215, dead 90

Part of Strabane – ill of fever 990, dead 75

For a total on the the Marquis of Abercorn’s estates, those ill of fever were 5,088 and 337 people had died. The total population of tenants on the Estates of the Marquis of Abercorn is recorded as 14,038. The proportion of attacks in these tables for a part of Tyrone, ⅓ to ¼ of the whole population, is believed to have been a fair average for the whole of Ireland.

In the parish of Ardstraw, in Co. Tyrone, with a population of about twenty thousand, 504 coffins are stated by the parish minister, to have been given to paupers in 18 months.

Nosologically, the science that deals with the classification of diseases), at the epidemic of 1817-18 presented several features of interest. It began with dysentery and ended with the same in autumn 1818. It was in great part typhus, but towards the end of the epidemic in Dublin, at Strabane and doubtless elsewhere, it changed to ‘relapsing fever’, that is to say, the sick person ‘got the cool’, about the 5th or 7th day, instead of the 10th or 12th, but was apt to have 1 or more relapses, or recurrences of the fever. The relapsing type was milder in its symptoms and was more rarely fatal. The average fatality of typhus was much less than in ordinary years, while a good many of the fatal cases came from the richer classes, to whom the contagion reached, the proportion of fatalities among them being noted everywhere as very high, up to 1 death in 3 or 4 cases.

The action of the English Government was thought, by some, to have been apathetic. Nothing was done to check the export of corn from Irish ports. CARLETON says “that there were scattered over the country, vast numbers of strong farmers with bursting granaries and immense haggards and that long lines of provision carts on their way to the ports met, or intermingled, with the funerals on the roads, the sight of which exasperated the famishing people. Several carts were attacked and pillaged, some strong farmers were visited and here, or there, a miser, or meal monger, was obliged to be charitable with a bad grace, but on the whole there was little lawlessness, less indeed, than in England in 1756 and 1766, or in Edinburgh in 1741. In the 2nd report of the select committee (named in Apr. 1818), they remarked that the rich, absentee landlords had given nothing. Another Act of June 1819, 59 Geo III. cap 41. defined the duties of officers of health and contained an important clause in relating to the spread of contagion by vagrants. By that time the epidemic was over, nor can it be said that the action of the Government, from first to last, had made much difference to its progress.

Vagrancy was the principal direct cause and behind the vagrancy, were usages and traditions, with interests centuries old, which made the landlords resolute not to pay poor rates on their rentals. It was not until 20 years after that, the English Poor Law was applied to Ireland (in 1839), whereby the pauper class were dealt with, as far as possible, in their respective parishes.

It will not be necessary to follow, with equal minuteness, the successive famines and epidemics of typhus, relapsing fever and dysentery in Ireland, to the great famine of 1846-49. After 1817, distress became chronic among the cottiers and small farmers. Leases had been entered into at high rents during the years of war prices and in the struggle for holdings, tenants at will offered the highest rate. When peace came and prices fell, rents were found to be excessive, not to say impossible. But in Ireland, with a rapidly increasing population, it was easier to put the rents up, than to bring them down. Other things helped to embarrass the poor cottager; he paid twice over for his religion; tithes to the parson, dues to the priest and he paid all the more of the tithe in that of the graziers, who were mostly of the established Church and the occupiers of the fertile plains had taken care to make potato land, titheable, at what date this innovation arose is not stated, but they had used their power in the Irish Parliament to resist the tithe on arable pastures. Again, the cottiers or cottagers paid, in effect, the whole of the poor rate in the form of alms; for the dogs of the gentry, kept all beggars from their gates.

Dr. MEASE, of Strabane, reported in March 1819, “The Epidemic Fever first made its appearance in Lifford gaol, towards the end of summer 1817, being introduced by a woman who came from a distant part of the county; she was attacked the very evening she arrived to visit her husband, a confined debtor. The disease was three several times extinguished in the gaol, being so often revived by fresh importations from the country, but for the last 8 months we have had no appearance of it.”

Dr. William HARTY, describes Dr. ROGANS records as a ‘very correct return of the Strabane Dispensary’. From a table of the Counties of Ulster, under the column of “registered sick”, are included not only those who were received into hospital, but also those who were attended at dispensaries.

The returns were comparatively few and of these few, they were defective. The deaths here recorded are ‘registered deaths’ and does not necessarily depict the correct numbers. The total probable deaths are considerably much higher.

Co. Donegal – no returns

Co. Londonderry – registered sick – 1,280; deaths 64

Belfast Town – registered sick – 3,000; deaths 170

Co. Antrim – registered sick – 1,600; deaths 92

Co. Down – registered sick – 1,545; deaths 59

Co. Armagh – registered sick – 163; deaths 11

Co. Fermanagh – registered sick not recorded; deaths 12

Co. Cavan – registered sick – 939; deaths not recorded

Co. Monaghan – registered sick – 1,037; deaths 53**

(To view the table which includes the ‘total of probable sick’ and the ‘total of probable deaths’ in each county, see below source by Dr. William HARTY pg. 20)

Of the registered sick in the whole of Ireland (150,000 in number) it is admitted that 6100, or about 1 in 25 died; now these were all under medical care and a great proportion of them enjoying the comforts of hospital whereas the remainder were, in a great measure, deprived of both these advantages. The registered sick besides, consist principally of those affected in the year 1818, a year during which the mortality was confessedly trivial, compared with that of 1817, particularly in Ulster; in many parts of that province the severity of the Epidemic had, in fact, passed by, before the inhabitants were provided with hospital accommodation, or with regular dispensaries. Though we are from this cause furnished with imperfect data for estimating the mortality of 1817, we are yet assured, that it far exceeded the mortality of the subsequent year, including even the deaths from dysentery. If therefore of the registered sick, 1 in 25 died, it may, I should think, without much exaggeration, be affirmed that of the remainder the disease was fatal to 1 in 15.

**Dr M’ADAM, in his account of the Epidemic at Monaghan, states that in the Autumn of 1817, mortality prevailed to such a degree that the living were scarce able, or willing to bury the dead. Parish coffins became a considerable item of public expense, so that it was necessary to practice economy in contracting for them.

Dr. Clarke in his survey of Ulster states that the disease was general throughout the county of Down, with the exception of Rosstrevor, a small bathing town.*

In co. Antrim, the only district which escaped the disease, was the island of Raghlin, owing to the position of the island and the active precautions of its

proprietor. In the county of Armagh, he did not hear of any district which escaped the contagion and the only observable difference between this, and the other counties, consisted in the extraordinary prevalence and mortality of the disease among the better classes of society! In county Monaghan, “no district, or class of society, was exempt from it: among the lower orders scarcely a house escaped, and where the infected were not speedily removed, it spread rapidly through the family.” In Tyrone the disease “appeared universally,” and in the neighbourhood of Strabane, “nearly one-fourth of the inhabitants were affected and in the mountain districts, the mortality is reported to have been excessive.’’ In the other counties of Ulster, the Epidemic was neither so prevalent, nor so fatal, as in Tyrone.

*Dr. Clarke observed, this town (Rosstrevor ) is out of the common thoroughfare, situated in a remarkably dry soil, with wide and airy streets, devoid of those miserable habitations where the lower orders of travelers, and mendicants are lodged and it is a fact acknowledged by every one, that ‘they’ were the great importers of infection throughout the country. The town is much resorted to in summer, by sea-bathers and other visitors, who circulate a great deal of money among the inhabitants, who are thereby induced to keep their houses clean and in good order. Large contributions were made by the neighbouring gentry during the scarcity, for the purpose of purchasing provisions, clothing, and fuel for the poor, which may be brought forward as an additional reason why they should have escaped an evil, so prevalent in the surrounding country.”

At Ballyshannon (Co. Donegal) the peasants took to the shore to gather cockles, mussels, limpets, and the remains of fish.

In the parish of Loughgall, near Armagh, containing a population of 8000 persons, above 1000 were ill before April 1818, according to the Report of the Select Committee of the House of Commons.

County Doctor’s Reports

Co. Armagh – Dr’s. William RYAN, Edward ATKINSON & Joseph BARCLAY, with Surgeons SIMPSON, COLVAN & MILLER – The Fever’s origin was spontaneous and the disease was greatly increased by the extraordinary influx of mendicants in the Spring of 1817. No part of the county escaped; the disease is very prevalent and fatal among the higher classes; ⅛ of the population must have suffered; the registered cases at Armagh are few (only 163) though 3000 and upwards were ill within a circuit of 3 miles of that town. The mortality varied as 1 in 3; 1 in 10; or 1 in 30; according to the station in life of the person; at the greatest height of the Epidemic the general mortality was 1 in 5. Dr. ATKINSON also notes “There never was a Fever since I commenced practice (which is 38 years) in this town or neighbourhood so prevalent or mortal.”

Co. Antrim – Dr. STEWART – The origin was generally spontaneous and the Fever had, with few exceptions, reached the ordinary standard before the end of 1818, except in Belfast and the marshy districts. It affected at least one-tenth, of the population; there are 469 registered cases at Lisburn; registered at Carrickfergus are 540 and in Randalstown there are 299, besides near 300 people who are out-patients. 92 deaths have been reported; about 1 in 14. The general mortality are still greater.

Belfast Town Co.’s Antrim & Down – Dr. M’DONNELL, Dr. THOMPSON & Dr. STEPHENSON

Co. Cavan – The Epidemic subsided in winter 1818 and a mild fever was still prevalent in 1819. The fever appeared first in the Gaol, and thence partially diffused; its general origin being spontaneous, and its great spread owing to the begging poor. The disease affected at least ⅛ of the population and no district or class of persons was exempt from it; scarcely a cabin escaped; in the town, ⅔ of the people having been ill; Between Aug. 1817 and Aug. 1818, 1037 people had been admitted to Hospital; 53 Deaths were reported; about 1 in 19: general mortality still greater. Between 20 and 30 died in the Gaol out of 130 prisoners.

Co. Donegal – Surgeon J. W. CRAWFORD and Doctor MEASE

Co. Down – Affected at least ⅙ of the population in towns without a Fever Hospital, scarcely a house escaped, and when the disease appeared in a poor man’s house, scarcely an individual escaped; in other towns not more than 1 in 4 were visited by the disease.” The registered cases are of 1545 at Newry; at Downpatrick 150 people were ill in August and Sept. 1817. Deaths in Newry Hospital 59; or 1 in 26. General mortality 1 in 15 at least; among the rich 1 in 5; “excessive in the mountainous districts.

Co. Fermanagh – Dr.’s MAGUIRE & NIXON. – The Fever was said to be spontaneous amongst the poor,and affected about one-fifteenth of the population. There were 168 convalescents in one month at Enniskillen with 12 deaths.

Dr. NIXON of Enniskillen reported April 1820

Fever was prevalent in the gaol of Enniskillen from August to November 1817; chiefly in September and October. 80 were infected and one died. The average population of the gaol is 80 and it will accommodate 150.

The contagion was evidently introduced from without. Every room, from which a patient was sent to hospital, was fumigated, whitewashed, and the bed, and bedding washed. I have not had a single case of Fever in the gaol since, though there are still some cases of Fever here, very few die.

Co. Londonderrry – Dr. CALDWELL – Suspected origin of the considered spontaneous Fever in the county, was spread by strolling beggars. It affected bout one-tenth of the population; at Derry City and New Town Limavady it was spread in greater proportion; Derry city received into the hospital 636 cases in the the last 5 months of 1817; in the Jail 17 and in the Infirmary 110; at Glendermot Dispensary, 534 were ill within a 3 month period of time.

Dr. CALDWELL of Londonderry reported April 1818. In answer to your queries, I will lay aside a determination, more than half-fixed, of giving myself no more trouble concerning public calamity from contagious diseases. I had spoken much, and written often, on the misfortunes arising from the Typhus-fever and could not at Derry, succeed in getting the fever tents fixed on the healthy hill, (having plenty of water), they being erected in a low damp situation, contiguous to the most sunk part of Bishop’s street.

I often entreated that the County Infirmary should be given for a temporary Fever Hospital, and wrote to the Committee of Gentlemen, No. 5 Parliament street, Dublin. I received no answer, and the Infirmary continued, useless to the county for suppressing this dreadful Epidemic, and the fever tents were kept in that inoculating situation for many months, before they were removed, and then, not till after great ravages.

The Epidemic Fever continued in the vicinity of Derry for 10 months, very violent, but has been little distressing for these last 3 months, and not worse than in former years. It is certain that cold, from deficiency of fuel, and bad weather with diet unfit for the human species, (potatoes not eatable and oats rotten, producing almost poisonous meal) were the chief exciting causes of this malady, and these causes were supported by the infamous corn laws, the destruction of commerce, and restraint on providential bounty. Anxiety of mind and weakness of body, seem to be the predisposing causes for the operation of infection on human beings and want of employment, preventing former active habits, greatly contributes to these predisposing causes.

March 1819 Dr. CALDWELL again observes that the County Infirmary refused every case of Fever, though the open market-house, was occupied partly with oatmeal for sale, and partly with patients in the Fever. The disease seemed to arise without any importation of foreign contagion, but there was a wonderful influx of beggars into Derry, in the summer of 1817, who brought with them a virulent small-pox and Fever, which increased greatly to the end of August. It has not been much more dangerous during 1818, than the ordinary Fever prevailing in this town. At this period there is not 1 for 20 in Fever, compared with the numbers affected in July and August 1817. In the time of the greatest mortality, 1 in 5 died.

Dr. Francis ROGAN of Derry reported March 1819 – The fever did not acquire an unusual height in the district around Strabane, until July 1817. The disease appeared to originate in the lodging-houses occupied by the begging poor; at least the contagion could not be traced to any particular source, and in these house,s the first cases of Fever occurred. It was at its greatest height in the months of August, September, and October 1817, and has since gradually declined, though the diminution in the number of patients has not been progressive, as a considerable increase was observed in June and July 1818. The number of Fever patients throughout the district is now fewer than at any former period, since the commencement of the Epidemic, though it still considerably exceeds that of former years. The disease does not now prevail to a tenth of its extent, when at its greatest height.

Dr. MAGINNESS of Londonderry reported Apr.1820, In reply to your queries, I have to state that Fever prevailed in the gaol of Derry for many months during the late Epidemic; between 40 and 50 were infected; 3 died (old people); the gaol contains near 200; the sick are separated from the healthy. Its mode of introduction could not be clearly ascertained, for it prevailed in the city and gaol at the same time. The introduction of contagion could not have been easily prevented, as a number of the debtors had Fever, and they are seldom refused the liberty of seeing their friends, whenever they please to visit them.”

Co. Monaghan – The Epidemic subsided in winter 1818 and a mild fever was still prevalent in 1819. The fever appeared first in the Gaol and thence partially diffused; its general origin being spontaneous, and its great diffusion owing to the begging poor. Fever affected at least ⅛ of the population and no district or class was exempt from it; scarcely a cabin escaped; in the town ⅔ of the people having been ill; Between Aug. 1817 and Aug. 1818, 1037 people had been admitted to Hospital; 53 Deaths were reported; about 1 in 19: general mortality still greater. Between 20 and 30 died in the Gaol out of 130 prisoners.

Downpatrick, (Co. Down) Dr. NEVIN reported Mar. 1818, that the disease did not appear to have been imported from any other place, though it must be acknowledged that, 2 months before the Epidemic commenced, a very malignant Typhus had appeared in Portaferry, a town about 7 miles distant. The greatest mortality was 1 in 9; the least 1 in 15.

Co. Armagh & Co. Down – Dr. Samuel BLACK of Newry, reported Apr. 1818 It appears to me, that the greatest bar to the extinction of contagion in country districts, is the total want of all ‘medical police’. Benevolence and charity may erect their Fever Hospitals and the advantages are as great as the duty is imperative, but though the wretch may be removed from his hovel to the hospital, yet that hovel is neither cleansed nor ventilated and substances retentive of infection remain, to communicate to the other members of the family its deadly influence, or to the wretched proprietor himself, when he returns from hospital, weak, exhausted, and in want of every comfort.

Co. Armagh & Co. Down – Dr. MORRISON also of Newry reported Mar. 1819, The late Epidemic commenced in this part of the country in, or about, the month of Aug. 1816, and became first alarming in December following. In April and the beginning of May 1817, the disease in some measure subsided, but in June 1817, it became truly formidable and continued so, till Sept. 1818. It appeared to have originated spontaneously; at least, I could never trace the contagion to any clear, or direct source. I have heard that it was first brought to this part of the country by some cargoes of old rags, landed at a northern port from the Mediterranean. This I do not believe. I believe that about 1 person in every 14, of this town and neighbourhood, has had an attack of Fever since the appearance of the Epidemic, or even since 1st June 1817. The average mortality, amongst the lower order has been about 1 to 18; and in the better ranks, 1 to 6.

April 1819 – “Fever, considered as an Epidemic, may be said to have disappeared in this town, though in the part of the country bearing N. E. from Newry. (distance 8 miles) it still exists to a considerable degree.”

Co. Monaghan Dr. James McADAM of Monaghan reported Mar. 1819 in Nov. and Dec. 1816, Fever broke out in the gaol of that town, without having appeared in any other part of the county, or being introduced from any other quarter. It made its way slowly, but evidently from the gaol into the town and as no notice was given that a malignant Fever raged in the former, an incautious intercourse was continued. After May 1817, mendicity and other causes multiplied the contagion and carried it with destructive violence through the town; as it increased in the town and country, it declined in the gaol. Between March and July 1817, 20 prisoners died out of a calendar of from 120 to 140. (prisoners) At different periods, I should think ⅔ of the population have been affected, in greater or less degree, the actual number I cannot even guess at, as I do not know the number of inhabitants in the county.

Co. Monaghan Dr. O’REILLY Carrickmacross reported Feb. 1819 – The disease has declined here very much, since the spring of 1818; the greater number of those, since affected, had a Fever of shorter duration, and less mortal, but were very subject to relapses. The great number of mendicants contributed to increase the contagion, some of them having actually the Fever, whilst others were just risen from the bed of sickness. Many of our association for relieving the distressed householders took the Fever, while attending to distribute provisions; being perfectly well going to the place, they came home with the disease, though provisions were generally given out in the open air; no age, sex, or condition of life was exempt from the Fever, but it was not so mortal amongst females.

(Co. Donegal) Dr. CRAWFORD Ballyshannon Mar. 1819 – It is impossible to say whether the contagion originated in this place; in many cases, it was evidently introduced by the starved hordes of mendicants and poor

tradesmen, that passed from place to place during the calamitous year of 1817. It has been liable to considerable fluctuations in respect to the number of sufferers; I do not recollect that it has, at any period, declined to the ordinary standard of Fever; it is at present very mild, and though very many are now labouring under typhus mitior, yet they are very few, compared with those ill in 1817. It is not possible to ascertain the number of deaths, or of persons attacked by the Epidemic, since its commencement in this county, but it has exceeded many thousands. In 1817, the mortality was very great, but since that, so few have died, that people are divested of all apprehension.’’

Co. Cavan Dr. MURRAY of Cavan reported Apr.1818 – Three prominent causes appeared to concur in producing that poverty and distress among the lower orders, in which (together with scanty and unwholesome food) the Epidemic would seem to have originated, viz: want of employment, the inclemency of the weather, and the desolating effects of the laws for suppressing private distillation. The first of these and its consequences

I consider the principal causes, predisposing the poor to disease and involving them in every kind of misery. As these causes still continue to operate, I think the Fever is not likely to disappear for a long time, fostered as it is by the filthy habits of the people, and propagated by the swarms of mendicants, which infest the country. In some cases I think the disease originated spontaneously. In Jan. 1820, He observes, the cases of Fever in this town and neighbourhood are now fewer than I have known in many years, when there had been no Epidemic. There have not been more than from 3 to ½ a dozen collected together, in our fever huts for many months, and I have not seen a case in private practice for a long time.

Co. Cavan Dr. M’DONALD also of Cavan reported Mar. 1819 – I cannot perceive any thing extraordinary in the present Epidemic; all its phenomena have been, over and over again, described by authors and the appearance of it last year was precisely that as described by Sydenham, as the continual Fever of 1673-1675; this year there was a peculiarity, which I do not find accurately stated by any author; this was a disposition in most cases, to end upon the 7th day by a well-marked crisis, whereas last year, the crisis seldom occurred before the 14th day and an observation of Hippocrates was fully verified, for after every such early crisis, they uniformly relapsed and the 2nd crisis was apt to happen on the 5th day.

Co. Cavan Surgeon ROE of Cavan reported Apr. 1818 – If any proof was wanting that bad air, or a want of ventilation was a great cause of Fever, I have merely to state, that the Fever which existed in the gaol of Cavan, to a greater or lesser degree, since January 1818, was almost exclusively confined to the debtors, who, from the unexampled crowded state of the prison, were obliged to sleep in small, very crowded and of course, ill-ventilated rooms. As a proof that bad food is a principal cause, I have merely to state a general observation, that, in the neighbourhood of Kilmore where a great number were employed as labourers, by the present Lord Bishop of Kilmore and by his truly humane and charitable directions, were supplied at a moderate price with wholesome provisions, Fever was much less prevalent than in other parts. Hence it will clearly be seen, that an improvement in the present state of the poor is the only true means of correcting the disease.

Dr. ROE Cavan Apr. 1820 again reported, I send you as correct answers to your queries as is in my power and I feel the greater pleasure in doing so, because they, in some measure, contradict the evidence given by the Rev. F. ARCHER on his examination before the House of Commons in May 1819; on which occasion he stated ‘that the prison was an unhealthy one, that it was one of the few gaols in which Fever was fatal and that the contagion was brought into the gaol by a woman who came to see her husband, that was to be hanged in a week, she brought it in with her, gave it to him and from him, it spread through the prison’.

All of these statements are without foundation, and I now have the pleasure of stating that the gaol of Cavan has been perfectly free from contagious Fever, for the last 18 months, and also that a large, convenient and comfortable hospital is now almost, ready for the reception of 20 males and 12 females. Mr. ARCHER’S last visit to this prison was so short, and his departure so unexpected, I had not an opportunity of mentioning the subject to him. I also have to add, that by the exertions of the local Inspector, Rev. George SPAIGHT and the weekly committee, of which the Lord Bishop of Kilmore is the principal director, several highly useful improvements have been made, at a very small expense, viz: the complete separation of one class of prisoners from another, particularly males from female, and with the additional advantage of making the day rooms, or kitchens, better lighted, more effectually ventilated and, of course, more healthy. Fever appeared in the gaol of Cavan so early as the month of Dec. 1816 and before it appeared in the town or neighbourhood with any severity; it continued during the year 1817 and part of 1818, and in the months of March, April, and May, the greatest number were affected by it. From its commencement, to the summer assizes of 1817, 49 persons were affected by it, not one of which died. From the summer assizes of 1817, to the lent assizes in 1818, there were 33 cases affected with Fever; of these, 25 were discharged cured, 5 died and 3 remained in hospital. Of the 5 who died, one was received into the gaol, ill of Fever, with which, he had been afflicted for some time; a 2nd was an old man who had a very intemperate liver; a 3rd concealed his disease for several days, and lived only a few days, after being sent to the lodge (our then temporary Fever Hospital); the other 2 died during my own confinement by Fever, which I contracted in the gaol in Dec. 1817. Such was my report to the High Sheriff, by order of the Judges, who came to this circuit in March 1818. A very few cases only, have since appeared and without any appearance of contagion, so that I may say not more than 88 were affected with Fever, of whom 5 died. This, I think, you will consider a small number, considering the want of proper hospital accommodation, the patients being obliged to occupy small rooms in cells, capable of holding only 2 persons; as also, the want of well-trained or intelligent nurse-tenders. The average population of the gaol is variable, the number has exceeded 200; I have known it as low as 64. It was intended to accommodate about 76. The contagion evidently arose within the gaol, owing to the excessively crowded and of course, ill-ventilated state of the debtor’s rooms, particularly at night. Few of the felons were affected; the woman whom Mr. ARCHER represented as bringing the Fever to the gaol, did not come into it for nearly 3 months after its 1st appearance; she attended her husband when ill of Fever, from whom, she contracted it herself. Cleanliness of person and of the apartments, ventilation, burning of tar and, as far as was practicable, the separation of the sick from the healthy, were the means most efficient in subduing the contagion. The above means, with the almost total prohibition of visitors, and friends, were the means adopted to guard against the introduction of the contagion. At present, this town and neighbourhood are almost perfectly free from contagious Fever.

THE FAMINE YEAR By Lady Wilde

Weary men, what reap ye? – golden corn for the stranger.

What sow ye? – human corpses that wait for the avenger.

Fainting forms, hunger stricken, what see you in the offing?

Stately ships to bear our food away, amid the stranger’s scoffing

There’s a proud array of soldiers – what do they round your door ?

They guard our master’s granaries from the thin hands of the poor.

Pale mothers, wherefore weeping? Would to God that we were dead –

Our children swoon before us, and we cannot give them bread.

Little children, tears are strange upon your infant faces,

God meant you but to smile, within your mother’s soft embraces.

Oh, we know not what is smiling, and we know not what is dying;

But we’re hungry, very hungry, and we cannot stop our crying.

And some of us grow cold and white – we know not what it means;

But as they lie beside us, we tremble in our dreams.

There’s a gaunt crowd on the highway – are ye come to pray to man,

With hollow eyes that cannot weep, and for words your faces wane

No; the blood is dead within our veins – we care not now for life;

Let us die hid in the ditches, far from children and from wife;

We cannot stay and listen to their raving, famished cries –

Bread! Bread! Bread! and none to still their agonies.

We left our infants playing with their dead mother’s hand;

We left our maidens maddened by the fever’s scorching brand;

Better, maiden, thou wert strangled in thine own dark-twisted tresses –

Better, infant, thou were smothered in thy mother’s first caresses.

We are fainting in our misery, but God will hear our groan;

Yet, if fellow-men desert us, will He hearken from His throne,

Accursed are we in our own land, yet toil we still and toil;

But the stranger reaps our harvest – the alien owns our soil.

O, Christ, how have we sinned, that on our native plains

We perish houseless, naked, starved, with branded brow, like Cain’s ?

Dying, dying wearily, with a torture sure and slow –

Dying as a dog would die, by the wayside as we go.

One by one they’re falling round us, their pale faces to the sky;

We’ve no strength left to dig them graves – there let them lie.

The wild bird, if he’s stricken, is mourned by the others,

But we – we die in Christian land – we die amid our brothers,

In the land which God has given, like a wild beast in his cave

Without a tear, a prayer, a shroud, a coffin or a grave.

Ha! but think ye the contortions upon each living face ye see

Will not be read on Judgment Day by eyes of Deity?

We are wretches, famished, scorned, human tools to build your pride,

But God will yet take vengeance for the souls for whom Christ died.

Now is your hour of pleasure – back ye in the world’s caress;

But our whitening bones against ye will rise as witnesses,

From the cabins and the ditches, in their charred, uncoffined masses,

For the Angel of the Trumpet will know them as he passes,

A ghastly, spectral army before the great God we’ll stand,

And arraign ye as our murderers, the spoilers of our land

Note- the above poem was actually written in Commemoration of the Irish Famine Years of 1846-1849, yet I find it applies during this time also.

Fever Deaths & News

transcribed by Teena from the Belfast Commercial Chronicle and Saunders Newsletter

4 Jun. 1817

An unhappy family, consisting a husband and wife, and four children, which some time ago came from Fintona to this country, (Belfast) have lately been all afflicted with Typhus fever. Poor, pennyless and without habitation, they lay down in the grip of a ditch, about a quarter of a mile from town, in a field contiguous to the Armagh road, where they were discovered by some humane persons, who supplied them with turf, milk and a blanket, to shelter them in some degree from the cold. A supply of whey had also been given to them, of which they drank great quantities. The father and some of the children have gradually recovered and are able to assist the remainder of the family. The circumstance was little known in Newry till yesterday, but having at last been stated to the committee for the relief of the poor, this unhappy family will be duly attended to and some habitation provided for them.

The recovery this family, under such singular circumstances, exposed as they were, to the open air and to the heavy midnight dews, may be urged as a proof of the efficacy of the refrigerating system in Typhus fever. We much fear that many other human beings, now experience sufferings similar to those endured by these poor people. Poverty and hunger compel them to shut the doors of their cabins and commence the trade of itinerant begging. Fatigue, bad diet and mental vexation bring upon them the direful affliction of Typhus fever. The doors of every family are then closed against them, lest its inmates should be visited with this contagious and deadly disease. Unable to proceed, they seek the miserable shelter of the first ditch that presents itself and trust the issue to the mercy of God.

1 Aug. 1817

Of a typhus fever at the Glebe House of the Parish Kilmore, Diocese Armagh, Richard BOURNE A. M. Rector of that Parish and for many years Minister of St. Werburgh’s Dublin.

21 Aug. 1817

At Newry of a typhus fever, in his 53rd year, universally lamented, Mr. Henry QUIN

3 Sept. 1817 – died

At Armagh, of Typhus Fever on the 28th ult. Mr. Samuel MAXWELL one of the most esteemed beloved and useful inhabitants of that city. So deeply was the lose this invaluable man felt by all his fellow citizens, the shops, on his decease, were universally closed through the town and all business suspended, till after his interment. He indeed possessed, in an eminent degree all those qualities which conciliate friendship and command respect The leading characteristics of his mind were promptitude, decision, perseverance, integrity and active benevolence. This excellent man died in the 36th year of his age.

6 Sept. 1817

At Bessbrook near Newry of a typhus fever Joseph NICHOLSON in the 59th year of his age

9 Sept. 1817 – died

Mr. Thomas SHARROCK, merchant, Downpatrick, who, notwithstanding every medical attention, was carried off on Monday last by typhus fever, in the 32nd year of his age, leaving a distressed wile, far advanced in pregnancy, and 5 children, to deplore their irreparable loss.

The Rev. Arthur FORDE, Protestant Clergyman Downpatrick, a most amiable and worthy character. He was attacked by the fever the same day as Mr. SHARROCK.

In Belfast of typus Fever, the Rev. Thomas JOHNSON, Methodist Preacher.

In Ballibay of a typhus Fever, Mrs. MARRON, wife of Mr. James MARRON of that town

Of typhus Fever, the Rev. Joseph HENRY of Ballentemple

In William street Newry, Mrs. STANLEY of a typhus Fever.

15 Sept. 1817 – died

The contagious fever which prevails in the country has carried off on the 8th inst. Captain M’COMB of Dromore

On the ship-quay, Londonderry of fever Mr. Alex M’CONN

At Donegal, on the 4th inst., after a short illness of the typhus fever, Mr. H. CANNEN, Merchant. We have seldom to record death more sincerely lamented. The numerous friends and acquaintances that accompanied his remains to a distant burying ground, evince how much they deplore this sudden stroke of Providence, which deprived his family of a most valuable parent and them of a kind and benevolent friend; his virtues will long remain written in the hearts and affections of the people of Donegal.

18 Sept. 1817 – died

Of a malignant fever, Mr. Samuel GREER of North street, Belfast

Near Randalstown of typhus fever, on Thursday the 11th inst, in the 34th year of his age, the Rev, Constantine O’BOYLE assistant Parish Priest of Drumaul.

25 Sept. 1817

On the 16th inst. in Ballymena, of a typhus fever, in the 50th year his age, Dr THOMPSON

27 Sept. 1817

At Newtownlimavady on Saturday last of a typhus fever Mr James THOMPSON, Tobacconist

6 Oct 1817 died

A few days ago, of typhus fever, which he caught whilst administering the consolation of religion to one his dying Parishioners. Michael M’GIN Roman Catholic Pastor of Clentibrit, County of Monaghan

At Downpatrick of typhus fever, Mr. Patrick STARKEY, merchant

Of typhus fever, Mr. John TAYLOR, merchant, Ballymena in the 40th year of his age.

20 Oct. 1817

At Cookstown of typhus fever, 63 years of age, Edw. PATTISON, Post master.

27 Oct 1817

Of fever, in the 21st year of her age. Miss Mary HILL, fifth daughter of Mr. Joseph HILL, Mullaghmenagh near Omagh.

At Londonderry of typhus fever, Mr. LOYD, land Steward to the Lord Bishop Derry.

29 Oct. 1817

At his house in Blessington street, (Belfast) of typhus fever, sincerely regretted, Geo. R. ARMSTRONG Esq. linen merchant. in the prime of life and with the highest prospects, but alas! “in the midst of life, we are death.”

30 Oct. 1817

Of typhus fever, in the 15th year of her age, Abigail, daughter of John ROGERS of Lisburn.

1 Nov 1817

At Armagh, of typhus fever, Major-General John BURNET commanding the Northern District, sincerely and universally regretted.

On Tuesday evening, the 28th ult. after a few days illness of typhus fever, in his 65th year, universally regretted, the Rev. Thomas CARPENDALE. Master of the Royal School Armagh

6 Nov. 1817

At Crieve, near Ballybay, County Monaghan, on the 27th ult. of typhus fever, Mrs. NELSON wife of Samuel NELSON Esq.

At Bridge-end Derry, of typhus fever, Mr. Henry SMITH

11 Nov. 1817

At his residence near Armagh, of a typhus fever, Mr. James M’WILLIAMS

Of typhus, Mr. Hugh BROWN, clerk of the Dissenting Congregation in Stuartstown.

20 Nov. 1817

At Carrickfergus of typhus fever, the Rev George HAMILTON, late of Armagh

In Armagh, of a typhus fever, Robert ATKINSON Esq.

At Armagh, Pescod TURNER Esq. of typhus fever, for many years Surgeon of his Majesty’s 4th regiment, or King’s Own

24 Nov. 1817

On the 15th instant, in Belfast, of a fever, James SLOANE Mathematician, aged 63

27 Nov. 1817

At Ballymena on the 21st inst. of a typhus fever, Mr. Wm. M’CRACKEN

Lately, at Loughbrickland of a typhus fever, Edward HUNDSON Esq.

4 Dec 1817

In this city, (Belfast) on the 26th ult. of typhus fever, James M’GUCKIN Esq.

Of a typhus fever, at Lough harbour Cottage, county Armagh, the Henry M’ILREE late Minister of the Presbyterian Congregation of Keady.

11 Dec 1817

At Verners Bridge on the 1st inst. of typhus fever, in the 49th year of her age, Mrs. HART, wife to Mr. William HART of same place.

Of a fever Mr. John FERGUSON near Newtownards aged 52 years.

In Derry, on Saturday last, of fever, Mr. ALEXANDER much regretted

15 Dec 1817

On Monday last of the typhus fever, the Lady of Mark A. LYSTER Esq., leaving a large family and numerous friends to lament her loss. Mr LYSTER had also been attacked by the same malignant disease, but has happily recovered.

6 Jan 1818

At Armagh of typhus fever in the 31st year of his age Mr. William YOUNG of that city, a man of rmost honorable principles

On the 26th ult. at Carrycue, of typhus Fever, Mr. George CATHER, aged forty-one

At Carrickfergus of typhus fever Assistant-surgeon STEWART of the 92nd Highlanders, second son of Patrick STEWART Esq. of Perth

20 Jan 1818

We lament to say that the typhus fever has raged with such violence in Co. Londonderry that no less than fourteen Roman Catholic Clergymen have fallen victim toit, in their humane attendance on the afflicted.

Of typhus fever at Ramelton on Tuesday the 30th ult. Robert M’KCAY Esq. aged 59 yrs. many years surveyor of excise there

page compiled by Teena from noted sources and~

“A History of Epidemics in Britain, Vol. 2′ By Charles Creighton 1894

“Historic sketch of the causes, progress, extent, and mortality of the contagious fever epidemic in Ireland during the years 1817, 1818, and 1819” and “Ireland Towns Map” by Dr. William Harty M.B.

https://archive.org/details/b2130502x/page/n7

“Rhyme with Reason” Chicago Publisher P.G. Smith 1911