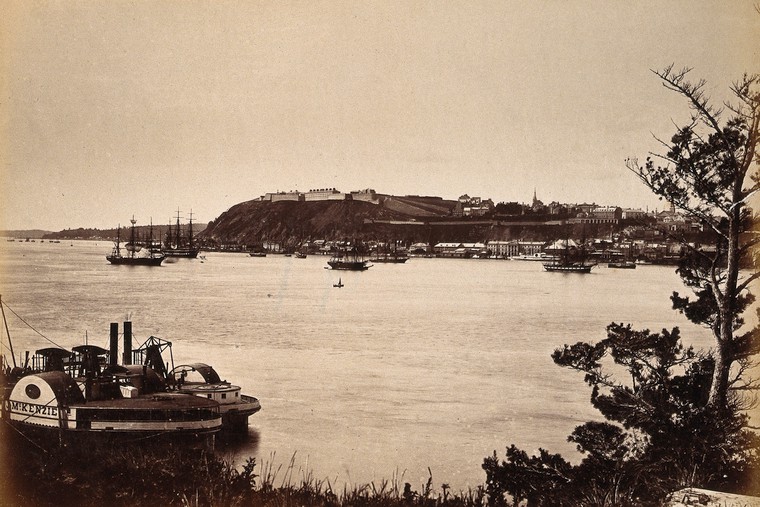

The name “Grosse Isle” means “Big Island,” but according to Dr. Montizambert, for many years one of the medical superintendents of the quarantine station there, (1909) this is a corruption of “Isle de Grace,” or Grace Island, under which title it was designated on old French charts. And this appears to be likely too, for Grosse Isle is not the biggest island of the cluster of 21 islands of the archipelago. The island is about 3 miles long and scarcely 1 mile wide. Indented with bays and situated in the open channel of the St. Lawrence, it lies 33 miles below Quebec, and forms one of the many similar islands, which stud the miles below Quebec.

In 1832 the Canadian Government, concerned about the Asiatic Cholera carried by emigrants entering Canada, created at Grosse Isle, an immigrant and quarantine station. The first buildings erected on the island were all located on the upper point of the island. (with the exception of a farm residence.) Those in the lower and center parts of the island, chiefly date from 1847. In 1878, three of the largest of these were destroyed by an accidental fire and many of the quarantine records were lost.

The first two chapels on the island, Roman Catholic and Protestant, were also erected in 1832. In fact, from the opening of Grosse Isle, spiritual consolation for the sick and dying appears to have been well provided for. It is the largest burial ground for emigrants of the ‘Great Famine’ outside Ireland. Today, it is also known as the ‘Irish Memorial National Historic Site’.

From their own beloved isle

These Irish exiles sleep,

Nor dream they of historic past,

Nor o’er its memories weep;

Down where the blue St. Lawrence tide

Sweeps onward, wave on wave,

They lie – old Ireland’s exiled dead,

In cross-crowned lonely grave.

Sleep on, oh, hearts of Erin,

From earthly travail free!

Our freighted sculls still greet you

Beyond life’s troubled sea;

In every Irish heart and home,

Where prayer and love abound,

Is built an altar to your faith

A cross above each mound.

No more the patriots word will cheer

Your humble toil and care

No more your Irish heart will tell

The beads of the evening prayer;

The mirth that scoffed at direst want,

Lies buried in your grave,

Down where the blue St. Lawrence tide

Sweeps onward, wave on wave.

Oh, toilers in the harvest field,

Who gather golden grain!

Oh, pilgrims by the wayside,

Who succor grief and pain!

And ye, who knew that liberty

Oft wields a shining blade,

Pour forth your souls in requiem prayer

Where Irish hearts are laid!

Far from their own beloved land

These Irish exiled sleep,

Where dream not faith – crowned shamrock

Nor iyies o’er them creep;

But fragrant breath of maple

Sweeps on with freedom’s tide,

And consecrates the lonely isle,

Where Irish exiles died.

poem transcribed from the Kilmore Free Press 22 Nov. 1888

Ulster Ports of departures for Emigrants 1846

Belfast

Donegal

Dublin

Londonderry

Newry

(This list is from Government reports and may not be complete)

Arriving Vessels, with which Contagious Disease was found on-board at the Grosse Isle Quarantine Station 1846

Barque ‘Ayrshire,’ port of Newry, Small pox, sailed 17 Apr.

Barque ‘Sir H Pottinger’ port of Belfast Measles saled, 15 Apr.

Barque ‘Highland Mary’, port Liverpool, Measles, sailed, 8 Apr.

Brig Barque ‘Margaret Pollock port of Liverpool, dysentery, Fever and measles, sailed 26th Apr.

Ship ‘Rockshire’, port Liverpool, Measles, 25th Apr.

Barque ‘Caithnesshire’, port Belfast, Fever and dysentery, sailed 23 Apr.

Ship ‘Elizabeth’ port Liverpool, Measles, sailed 26th May

Ship ‘Virginia’ port Liverpool Small pox sailed sailed 2nd June

Ship ‘Belinda’ port Belfast Small pox and measles sailed 3rd June

Ship ‘Mertoun’ port Belfast, Fever, sailed 28th May

Ship ‘John Boulton’ Liverpool Fever sailed 2nd June

Barque ‘James Moran’ port Liverpool Measles sailed 13th June

Ship ‘Rockshire’ port Liverpool, Dysentery sailed 10th Sept.

Number of Persons who received Assistance to enable them to Emigrate during the Season 1846 from the report of A.C. BUCHANAN

Vessel / port. arrival date/ who provided funds/ # of persons/’Naparvinia’, Dublin, 29th May, landlord or private funds, 120

‘Industry’, Dublin, 30th May, landlord or private funds, 143

‘Lady Gordon’, Dublin, 13th Jun., landlord or private funds, 5

‘Defence’, Liverpool, 16th Jun., landlord or private funds, 40

‘Mary Lyall’, Dublin, 16th Jun., Parish funds, 7

‘Londonderry ‘, Londonderry, 18 Jun., landlord or private funds, 14

‘Miltiades’, Belfast, 24 Jun., landlord or private funds, 21

‘Pursuit’. Liverpool, 24 Jun., landlord or private funds, 8

‘Odessa’ Dublin, 27 Jun., landlord or private funds, 24

‘Belinda’, Belfast, 20th Jul., landlord or private funds, 93

‘Brindo’, Donegal, 24 Jul., landlord or private funds, 15

‘Marquis Abercorn’, Londonderry, 2nd Oct. landlord or private funds, 3

In the ship Londonderry there were 14 persons sent out by the Londonderry Union, who received the sum of 10s. each amounting to 8£ 15s. sterling, which had been remitted to this office for their benefit after arrival.

Among the passengers per ‘Marchioness of Abercorn’ from Londonderry, 493 in number, there were some very respectable farmers. Nearly the whole of these people came out to join their friends, a large number of whom are settled in the Home, and Simcoe districts. Many had received assistance from this country to enable them to emigrate and I was consequently obliged to give assistance to 35 persons to enable them to proceed.

In the ‘Belinda’ from Belfast, there were a number of poor families sent out by the Coleraine, Armagh, and Magherafelt Unions, who received the sum of 10s. each, from the master on landing here. Many of them, more particularly those from the Coleraine Union, were very helpless, consisting of sickly people and widows with families of helpless children. One or two of these families have been inmates of the hospital ever since their arrival here and are now dependent on the charitable institutions in this city for their support.

The passengers per ‘Belinda’ from Belfast, 425 in number are respectable looking people. There had been a good deal of sickness, among them 12 children had died during the passage of small pox and about 40 of the passengers were left at the Grosse Isle Hospital, where the ship was detained for six days. The passengers all speak in the kindest manner of the care and attention which Captain KELLY showed them during the passage and his unremitting attention to the sick. About 30 of the passengers are going to the States, the rest to the Newcastle, Home, and Simcoe Districts, 93 persons by this vessel were sent out by the following unions and received from Captain KELLY the sum of 37£ 15s. sterling, being at the rate of 10s. to each adult and 5s. to children viz: Coleraine Union 61 adults and 40 children; Armagh Union 15 adults and 5 children; Magherafelt Union 30 adults and 9 children. Those sent out by the Coleraine Union were mostly old and sickly people and helpless children, many of whom I fear will never be able to earn their support in this country. The others appear stout, healthy, men and women, all apparently willing to work.

The emigrants from Sligo and Donegal, 545 in number, are all poor. They landed in good health. One third of them are going to the United States. A number of the young men intend remaining here for employment and the remainder proceed to different parts of the province to their friends.

The passengers per ‘Aberdeen’ from Liverpool are all Irish, from the counties Cavan, Cork, Waterford and Tipperary. They have gone chiefly to the Ottawa, Johnston, and midland districts, and were, with the exception of two families 12 in number, able to pay their way.

The emigrants from the port of Liverpool, 750 in number, are all Irish, of which fully one half intend proceeding to the United States. On board the ‘Defence’ from that port, there were 40 persons sent out by their landlords. They are from the county Monaghan and were provided with a free passage. They were without means on landing here and were assisted with a free passage to their friends in Upper Canada.

The passengers per ‘Sea King’ and ‘Virginia’ from Liverpool, 508 are nearly all Irish. About 80 of the passengers per ‘Sea King’ are going to the United States, the remainder intend settling in Upper Canada. Those from the ‘Virginia’ all appear inclined to remain in the province. They are from the north of Ireland and generally poor. This vessel was detained seven days in quarantine and left between 60 and 70 of her passengers in the island, with small pox, 65 adults and 45 children were forwarded up the country from this vessel and 16 from the ‘Sea King’.

Week ending 27th Jun.1846; 4,568 emigrants have landed at this port during the past week, generally in good health.

Week ending 31st Jul. 1846; 2164 emigrants landed at this port during the past week, three fourths of whom are Irish.

Owing to the low rates of passage on alternate days on the route between this city and Montreal, I have not been called upon for much assistance. The number assisted is 286 persons equal to 200 adults, chiefly from the ‘Mertoun’, ‘John Bolton’, ‘Minna’ and ‘Bosphorus’. There was a good deal of sickness on board the ‘Mertoun’, 7 deaths occurred during the the passage and 27 cases were admitted to the quarantine hospital.

Employment is plenty at this season and persons desirous of it can procure it without difficulty. Masons and stone cutters are in much request on the Government works wages 7s 6d. per day

Week ending 22nd August 1845

The emigrants arrived during the period included in this return number 1845, of whom 133 are Germans; 225 Scotch; 40 English; and 1440 Irish, of the latter number 394 sailed from Liverpool. They, with the exception of those on board 3 of the vessels, landed generally in good health. Several vessels have, however, had very long passages, the average being over 50 days. The passengers are principally of the agricultural class and with, but limited means. Their destination is chiefly to Upper Canada, but a considerable number are going to the United States.

Week ending 30th of October 1846

The emigration for this season may now be considered as closed. Those who have arrived during the period embraced in this return, have been in good health. They consist of farmers, labourers, and a few mechanics, and have all emigrated to join their friends, or with a particular destination in view.

The great majority of them are Irish and all very poor. A large number of those by the ‘Rockshire’ from Liverpool, had left their homes at this late season, in consequence of the failure of the potato crop, fearing that if they should delay until next year they would not then have the means of paying their passage. As it was, they landed here quite destitute and required assistance from this department to enable them to proceed to their friends.

In Paper No 8 of the Appendix will be found a statement of the distribution of the emigrants of the year, compiled from the monthly reports received from the chief Agent in Canada West and the local agents of the department. Of the total immigration by the route of the St Lawrence, Mr HAWKE estimates that the large proportion of 24,655 have arrived in Canada West. The number who have arrived, via the route of the United States, is stated at 2,864, which makes the total immigration into the western section of the province during the year upwards of 27,500 souls. The difficulty of ascertaining with correctness the number of persons who have proceeded from Canada to the United States, along our extensive frontier, must be obvious. Mr HAWKE, after strict inquiry from the sources within his command, estimates the number who have left Canada West at about 2,000 persons, less than the amount of the immigration we have received by that route.

The largest portion of this number have proceeded direct from Montreal, by the route of St John’s and Lake Champlain, having emigrated with that intention and have been induced to choose the route of the St Lawrence as being much cheaper than the passage direct from Great Britain, to any of the United States ports. I may here remark that during the greater part of this last season owing to the competition among the steam boat proprietors on the St Lawrence, to Montreal and on Lake Champlain, an emigrant might be conveyed from this port to Albany, the centre of the States of New York, for about six shillings sterling, or less than half the sum it would require to convey him to Kingston.

The Quarantine hospital Grosse Isle during the past season-

upon a comparison of this Return, with that of former years, it will be observed that there has been a great augmentation in the number of sick amounting to double that of most previous years. This increase in the number of sick was expected from the misery and distress that prevailed throughout Ireland last winter, owing to a deficiency of wholesome food. The prevailing type of disease independent of the ordinary epidemics was low fever, with bowel complaints, such as are usually caused by want. The number of passenger vessels inspected by me at the quarantine station during the season was 206, having on board 32,753 passengers. The deaths on shipboard were this year proportionably more numerous than previous years, there having died on board of vessels on the passage out 204 souls and in the Quarantine Hospital 68. The names, ages, and other particulars, connected with these last, are given in paper B. The total number of deaths on the voyage and in the quarantine hospital was 272, of these 100 were adults; 110 children under fourteen; and 62 infants. Fever broke out and prevailed among the passengers of 14 vessels. measles in 5 and small pox in 8.

The following casualties on the voyage resulting in death took place; A boy was killed from a fall into the hold on board the ship ‘Marchioness Abercorn’; 1 was drowned by falling overboard from the brig ‘Governor’; one was killed on board the ‘James Fagan’, by being crushed by one of the boats breaking loose; a female died in childbirth on board the schooner ‘Coquette’; and another from the same cause on board the ‘Jane Black’; a boy was drowned by falling overboard from the ‘Nancy’; a man from the same accident on board the ‘Davenport’; and another from on board the ‘John Francis’.

A considerable number of pauper emigrants have been sent out this season from the Irish Poor law unions. Much sickness has prevailed among these, especially in those that arrived by the ship ‘Belinda’ from Belfast. It is to be regretted that it should not be found necessary to supply these people, many of whom had the appearance of having suffered long from misery, with any other provision for the voyage than a pound of meal per day. They contrast very unfavourably with those sent out under similar circumstances from England, these are generally sent in charge of a medical man, and are supplied with animal food, bread, flour, rice, and medical stores and comforts, in consequence of which, I rarely find sick among them, unless epidemic disease has been brought on board. I always understood the pound of biscuit oatmeal, or Indian corn meal, which the vessel is bound by law, to furnish daily to each adult, to be merely a guarantee against the starvation brought on formerly by the improvident use which the emigrant made of his own stores and to be, by no means, intended to constitute his only support, as in the case of the Irish paupers in the ‘Belinda’ and other vessels, to whom a pound of damaged Indian meal, per day, was their only food. If necessary, I might here cite as evidence of the advantage of a liberal supply of wholesome food in warding oft disease even in a crowded emigrant vessel, the case of the German settlers who arrived this year, these people were supplied abundantly with animal food, bread, flour, lime-juice and beer, and though their voyages were longer than vessels coming from Great Britain, in the case of one vessel extending to eleven weeks, yet out of eight vessels having on board 902 passengers, I had only to admit 7 to hospital.

Letter from Ardnaglass (Co. Donegal) 6th September 1846

Dear Father and Mother

I received your kind and affectionate letter dated 24th May which gave us great pleasure to hear of your being in good health as it leaves us at present thank God for his mercies to us. Dear father and mother pen cannot dictate the poverty of this country at present, the potato crop is quite done away all over Ireland and we are told prevailing all over Europe. There is nothing expected here only an immediate famine. The labouring class getting only two stone of Indian meal for each day’s labour and only three days given out of each week to prolong a little money sent out by Government, to keep the people from going out to the fields to prevent slaughtering the cattle, which they are threatening very hard they will do before they starve. I think you will have all this account by the public print before this letter comes to hand. Now my dear parents, pity our hard case and do not leave us on the number of the starving poor and if it be your wish to keep us, until we earn at any labour you wish to put us to, we will feel happy in doing so. When we had not the good fortune of going there the different times ye sent us money, but alas, we had not that good fortune. Now my dear father and mother, if you knew what hunger we and our fellow countrymen are suffering, if you were ever so much distressed, you would take us out of this poverty Isle.

We can only say, the scourge of God fell down on Ireland, in taking away the potatoes, they being the only support of the people. Not like countries that has a supply of wheat and other grain. So dear father and mother, if you don’t endeavour to take us out of it, it will be the first news you will hear by some friend of me and my little family to be lost by hunger and there are thousands dread they will share the same fate. Do not think there is one word of untruth in this, you will see it in every letter and of course in the public prints. Those that have oats they have some chance, for they say they will die before they part any of it to pay rent. So the landlord is in a bad way too. Sicily BOYERS and family are well. Michael BARRETT is very unwell this time past, but hopes to recover. John BARRETT is confined to his bed by rheumatism. The last market oatmeal went from 1£ to 1£ 1s per cwt. As for potatoes there was none at market. Butter 5£ per cwt; pork 2£ 8s. per cwt and everything in provision way expected to get higher. The Lord is merciful, he fed the 5000 men with five loaves and two small fishes. Hugh HART’S mother is dead, he is in good health. So I conclude with my blessing to you both and remain your affectionate son and daughter

Signed Michael and Mary RUSH

Accounts and Papers of the House of Commons, Vol. 39 published 1847

https://bit.ly/3bj4nzi

6 Apr. 1847 (extracts) statements taken from the report of A. C. BUCHANAN Esq., chief emigration agent at Quebec,in a series of papers relative to emigration to the British Colonies of North America (Parliamentary, No. 120, presented last February.)

The emigrant on engaging his passage is informed that he will receive a pound of oatmeal, flour, or biscuit, each day during his passage, but on getting to sea finds that one-half of this allowance is replaced by Indian corn meal. This description of food although highly valuable, under different circumstances, is not proper for issue throughout along voyage, to people who have been wholly unaccustomed to its use and who do not know, how indeed, to prepare it. Dr. DOUGLASS has found that a great extent of sickness prevailed in the vessels in which the meal was used.

‘there was a large number of the Irish emigrants in a state of destitution as to clothes and bedding far exceeding anything I ever before witnessed’

Passengers ship “Helen Thompson” Londonderry for Quebec, Canada 18 Feb. 1847-19 Apr. 1847 Captain GRAY (544 tons)

Samuel POLLOCK and family, Sarah Jane, John 8 years, Elleanor 5, Eliza 4, Hamilton 2, James 6 months and Rebecca HUNTER 9, Loughneas

Jane JOHNSTON and family, Margaret, James and Mary Jane 7 years

Henry and Nancy CARRAGHER, Maghera, Co. Londonderry

Biddy KEARNEY, Maghera, Co. Londonderry

Lewis WILLIAMS and family, Catherine, Samuel, William, Mary Anne 6 years and Catherine Eliza 4, Moville, Co. Donegal

Patrick and Mary McGOLRICK, Omagh, Co. Tyrone

James SWEENY and family, Catherine, Edward, James 12 years, Margaret 8, Rosannah 1, Owen 6 months, Omagh, Co. Tyrone

Sarah PROTHERICK, Omagh, Co. Tyrone

William LAWSON and family, Isabella, William, James and Matilda, Castlederg, Co. Tyrone

Ellen McCARRON and family, John, William, Jane 13 years, Sarah 11, James 9, Robert 7, Alexander 3, Eliza 5

Margaret McGARR and family, Mary 5 years and James 3, Castlederg, Co. Tyrone

James McCARRON and family, Hanna, John, Miller 12 years and James 8, Castlederg, Co. Tyrone

Thomas ARBUCKLE and family, Catherine, John, Isabella, James 13 years, Thomas 11, Joseph 8, Mary 7, Isaac 5, Eliza 4, William 3, Catherine 14 and Jane 3 months, Newtownstewart, Co. Tyrone

Eliza STEWART, Newtownstewart, Co. Tyrone

Henry McGORMAN and family, Isabella, Samuel, Sarah 9 years, Elizabeth 7, Catherine 4 and William an infant, Newtownstewart, Co. Tyrone

Martha McCONNELL and family, John, George and Ann, Newtownstewart, Co. Tyrone

James GLASS, and family, Isabella, Mary 12 years, Eliza 9, Isabella 5, John James 2, with Mary MITCHELL 13 years and Martha GLASS 13, Newtownstewart, Co. Tyrone

Patrick MELLON and family, Jane, Robert, Sarah, Margaret, Jane 13 years, Newtownstewart, Co. Tyrone

James CONNOLLY and family, Bid, Mary Margaret, Sarah 13 years, Kitty Ann 11, James 9, John 7, Henry 5, Ellen 3, Patrick 6 months, Newtownstewart, Co. Tyrone

Hugh BLACKBURN and family, Jane, Robert, Patrick 11 years, Hugh 9, William 6, Newtownstewart, Co. Tyrone

James and Elizabeth BEATTY and children George 9 years, Eliza 6, Alexander 3, William 6 months

Patrick McCANNA and family, Catherine, John, Margaret, James 14 years, Mary 12, Catherine 7, Phillip 5, Newtownstewart, Co. Tyrone

Daniel McCANNA and family, Margaret, Eliza, Mary, Henry, Catherine 14 years, Patrick 13, Newtownstewart, Co. Tyrone

John McGOADRICK and family, Mary, Daniel, Margaret Ann, John, Patrick 13 years, Catherine 11, Hugh 9, James 7, Thomas 5

James McGURK and family, Catherine, Arthur, Catherine, Patrick, Mickey 13 years, James 11, John 10, Hugh 8, Mary 7, Neely 4, infant 6 months, Newtownstewart, Co. Tyrone

John CLARKE Coleraine, Co. Londonderry

Rebecca CRETON, Kesh, Co. Fermanagh

William GRAHAM, Derry

Joseph GRAY, Newtownstewart, Co. Tyrone

John and Mary LAIRD, Newtownstewart, Co. Tyrone

James BEATTY, and family, Rhoda, Ann, William, Mary, George 13 years, Jane 11, James 9, Newtownstewart, Co. Tyrone

David and Margaret GREEN and family, John 4 years, Mary Jane 2, James 9 months, Maguiresbridge, Co. Fermanagh

Bridget McCUSKER, Maguiresbridge, Co. Fermanagh

William SMYTH and children, Mary 12 years, Margaret 9, William 7, Isaac 4, John 3 months, Maguiresbridge, Co. Fermanagh

James BROWN and family, Jane, John, James 13 years, William 11, Francis 9, Jane 6, Maguiresbridge, Co. Fermanagh

George HUTCHISON, Newtownstewart, Co. Tyrone

John and Jane HAMILTON and family, James 11 years, John 9, Eliza 7, Thomas 5, Margaret 2½, William 6 months, Castlederg, Co. Tyrone

John McCORMICK and family, Eleanor, Isabella, Jane 12 years, Margaret 8, Henry 2½, Eleanor 6 months, Castlederg, Co. Tyrone

Henery CONNELLY and family, Mary, William, Jane 13 years, Margaret 11, Mary 9, Biddy 7, Henry 5 and Rosey 3, Castlederg, Co. Tyrone

Hugh McMANUS and family, Catherine, Eleanor, Edward 13 years, John 11, Patrick 9, Castlederg, Co. Tyrone

Edward CONNELLY and family, Nelly, Biddy 9 years, Patrick 7, John 5, Mary 3, Castlederg, Co. Tyrone

Mary McMENAMIN, Castlederg, Co. Tyrone

Anthony THOMPSON, Kesh, Co. Fermanagh

Feiry (?) MAGUIRE and family, Mary, John, Patrick Mick, Catherine 13 years, Felix 8, Bridget 6 and Mary 3, Enniskillen, Co. Fermanagh

John AUSTIN, Muff, Co. Donegal

James PATTON, Ballybofey, Co. Donegal

Thomas GREENLEESE and family, Ann, Margaret, Ann, Moses, John 13 years, Thomas 11, Sarah 9, Brookeborough, Co. Fermanagh

William and Margaret STORY and children, Thomas 12 years, John 7, Robert 2, William 6 months, Brookeborough, Co. Fermanagh

William RIDDLE and family, Susan, Eliza, James, John, Hugh 12 years, Henry 10, Janet 4, Robert 3 months, Coleraine, Co. Londonderry

Isabella SIMON and family, Thomas, James, Martha, Mary Ann, Coleraine, Co. Londonderry

Nancy SIMON and children, Eliza 4, Janet 9 months, Alexander 12, Jane 10, Isabella 8, Mary 6, Coleraine, Co. Londonderry

Matilda BEETH, Coleraine, Co. Londonderry

Robert WALKER and family, James and Alexander, Coleraine, Co. Londonderry

Daniel McALISTER, Newtownlimavady, Co. Londonderry

Mary WALLS, Castlederg, Co. Tyrone

James PATTERSON and family, Joseph, Charles, Eliza, Newtownstewart, Co. Tyrone

Thomas McLAUGHLIN, Newtownstewart, Co. Tyrone

Jane WILSON and children, Joseph 12 years, Ann 10, Thomas 8, Newtownstewart, Co. Tyrone

Daniel and Alexander GILROY, Enniskillen, Co. Fermanagh

William CRAIG, Enniskillen, Co. Fermanagh

P. GILROY, Enniskillen, Co. Fermanagh

James and Bridget MURPHY, Enniskillen, Co. Fermanagh

Anne CRAIG, Enniskillen, Co. Fermanagh

Michael MULLEN and family, Isabella, Mary, Rosanna 12 years, Bridget 10, Michael 8, Hugh 6, Omagh, Co. Tyrone

John KEENAN Omagh, Co. Tyrone

James McBRIDE, Omagh, Co. Tyrone

Thomas and Anne MACABE and children, Margaret, Thomas, Anne 10 years, Isabella 7, Sarah 5, Maguiresbridge, Co. Fermanagh

Samuel and Jane ELLIOT and William 6 months, Maguiresbridge, Co. Fermanagh

William and Jane GARRELL and children, Robert 13 years, George 11, Maguiresbridge, Co. Fermanagh

Allen JEMAISON (?) and children, Mary Anne 13 years, Sarah 11, Maguiresbridge, Co. Fermanagh

John and Anne FRAZIER Maguiresbridge, Co. Fermanagh

Mary Ann and Elizabeth KELLY, Maguiresbridge, Co. Fermanagh

William and Mary RAMSAY and children John 13 years, Elizabeth 11, Mary 6, Isabella 3 and Henry 9 months, Maguiresbridge, Co. Fermanagh

John CHITTICK and child, Christopher 13 years, Maguiresbridge, Co. Fermanagh

James HUMPHREYS and family, Margaret and Andrew, Kesh Co. Fermanagh

Thomas McDOUGLAS, Kesh, Co. Fermanagh

Peter HALEY and child, James 13 years, Kesh, Co. Fermanagh

James MULDOON and family, Ally, James, John 12 years, Patrick 10, Ann 7, William 4, Thomas 2, Kesh, Co. Fermanagh

Catherine LUNNY, Kesh, Co. Fermanagh

Janet TERNAN, Kesh, Co. Fermanagh

Liddy DARRAGH and family, Margaret, Christina (?), Elizabeth 12 years, Ann 10, Enniskillen, Co. Fermanagh

William BROWN, Newtownlimavady, Co. Londonderry

Margaret MACKIE, Brookeborough, Co. Fermanagh

John BRESLIN, Enniskillen, Co. Fermanagh

Margaret CREARY Enniskillen, Co. Fermanagh

Mathew and Robert McCOMB

Betty JOHNSTON and child, John 12 years, Newtownstewart, Co. Tyrone

Alexander and Isabella McLAUGHLIN, Newtownstewart, Co. Tyrone

James FLEMING, Convoy, Co. Donegal

Dennis AITKAN, Stranorlar, Co. Donegal

Mark WHITE, Newtownlimavady, Co. Londonderry

Mary CLARKE, Newtownstewart, Co. Tyrone

Rosy KEARNEY, Maghera, Co. Londonderry

John McKEE, Newtownstewart, Co. Tyrone

Total souls 371 equal to statute adults 277

Net sum received £765 5s. 3d.

Cancellations

Neel FRIEL and family, Catherine, Nancy, Ann 3 years and Hugh 9 months, Ramelton (?), Co. Donegal

Dennis McBRIDE, Rathmullan, Co. Donegal

Patrick and Mary BEGLEY and children, John 4 years, Edward 2, Keatty 3 months, of Tamney

John COLLINS and family, Jane, Mary, James and John, Newtownstewart, Co. Tyrone

Sarah SMYTH and child, Anne 2 years, Maguiresbridge, Co. Fermanagh

Thomas McGARREN and family, Ellen, Patrick, Martha and Mick, Enniskillen, Co. Fermanagh

Thomas and Judy MAGUIRE and children, Anne 10 years, Margaret 9, Mary 7 and infant 6 months, Enniskillen, Co. Fermanagh

Mary Jane PATTON and children, Francis 8 years, Anne Jane 10, Ballybofey, Co. Donegal

William GREENLEESE, Brookeborough, Co. Fermanagh

Nancy WALKER, Coleraine, Co. Londonderry

Robert PATTERSON, Newtownstewart, Co. Tyrone

William RAMSAY and family, Rebecca, Margaret, Robert 13 years, Eliza 9, Mary Ann 7, Matilda 5, Maguiresbridge, Co. Fermanagh

Child of John CHITTICK, Maguiresbridge, Co. Fermanagh aged 9 months

Sarah Jane HOUSTON, Coleraine, Co. Londonderry

Passenger list Ship’ Sesostris’ for Quebec 10 Apr. – 11 May 1847 Captain FRAZER, (606 tons)

George and Margaret WORLIN

Ann CAMPBELL

Samuel and Mary ARBUCKLE and children William 13 years, Eliza Jane 11, Mary 9, Ann 7, Hannah and Samuel 4, John 2 and Watty 9 months, Donagheady, Co. Tyrone

Booking cancelled for James ARBUCKLE

James and Sarah CAMPBELL and children Hugh 5 years, John 3 and William 9 months, Cappagh, Co. Tyrone

James COX and family Mary, Eliza, William J. 7 years, Robert 5 and Isabella 3 with Joseph BLAKELY, Ballyconnelly

Robert and Martha ADAMS and children Robert 10 years, William 8, Margaret Jane 6, Hamilton 4, Matilda 2, David 6 months with James BROWN, Londonderry

Ann TONAR, Glenswilly, Co. Donegal

William and Martha KELLY and children Eliza 13 years, Maria 12, Ann Jane 10, Margaret 8, Charles 6, Theophilus 5 and Matilda 6 months, Tullyardin

Andrew ARMSTRONG and family Elizabeth, James, Richard, Andrew 13 years and Thomas, with Mary LYTLE, Enniskillen

Charles LAFFERTY, Strawbridge, Co.

Oliver BROWN, Donemana, Co. Tyrone

James MONAGHAN and children James, William 13 years, Charles 12, Owen 10, William 7, Biddy, Pettigo, Co. Donegal

John and Mary MONAGHAN and children Biddy 4 years and Ellen 9 months, Pettigo, Co. Donegal

Peter and Margaret McCAFFRY, Enniskillen

William and Jane FLEMMING and children Joseph 4 years, Rebecca and Isabella 2½, Jane 9 months with Eliza NOBLE 11 years and Mary Ann NOBLE 9, Dromore, Co. Tyrone

James RIDDLE and family Jane, William, George 13 years, Archibald 11, John 9, Mary 7, Hugh 5 and Robert 9 months, Maguiresbridge, Co. Fermanagh

Mathew and Jane WILSON and children Robert, Jane 13 years, William 12, Mathew 11, Jane 9, Rebecca 7, Johnston 5 and Mary 1½ with Margaret ROWAN, Castlederg

Isabella WILSON and family John, Ellen, James 13 years, Margaret 12, William 10 and Charles 7, Omagh

Andrew CUNNINGHAM and family Elizabeth, Robert, Sally 13 years, Charles 11, Ellen 9 and Betty 7, Omagh

Denis and Mary McANULTY and children Mary, Daniel, Marjorie 12 years and Denis 10, Newtownstewart

Pat McLAUGHLIN and family Dan and Ellen, Newtownstewart

Joseph and Mary Ann CUNNINGHAM and family Rebecca and Alexander 9 months, Newtownstewart

Booking cancelled for Eliza CUNNINGHAM and James CUNNINGHAM 6 months

James KING, Newtownstewart

David MILLER Newtownstewart

James and Catherine QUINN and children Dan 12 years, Catherine 9, James 6 and Mary 2, Newtownstewart

John and Jane COLLINS and children Mary 10 years, James 8 and John 6, Newtownstewart

William and Isabella HOOD, Newtownstewart

Joseph PARK, Newtownstewart

Ruth HAMILTON, Newtownstewart and Jane 10 years

Andrew and Mary McCAUSLAND and children John 13 years and Eliza Jane 6, Mullaghmore

Elizabeth and Catherine STARRETT, Mullaghmore

William and Margaret MOORE and children Catherine Jane 3 years and Eliza Ann 3 months, Pettigo

Hugh and Jane KNOX, Castlederg

John EMMERSON and family Isabella, Robert, Edward, Thomas and James 13 years, Enniskillen

Thomas and Mary BROOKE, Enniskillen

James and Margaret BOTHWELL and child Elizabeth 2 years, Enniskillen

Andrew WELDON, Fintona, Co. Tyrone

James McCOOL, Spenig (?)

Jane LYONS, Spenig (?)

George and Rebecca STEWART and children Rebecca 13 years, Sarah 10, Fanny and Mary 6, George 3 and James 9 months, Spenig (?)

William and Jane BALFOUR and children James 13½, Isabella 11, Mary Jane 10, William 8, Robert 7, Margaret 6, George 4, Edmond 9 months, Enniskillen

Ellen PATTERSON and family Jane, John, Catherine, Thomas, William 11 years, Ellen 9, Mary 9 months, Coleraine

Catherine GORMLY and family Henry, Charles, Jane, Ann, John, Mary, Ellen 1½ years and Charles 3 months, Dromore, Co. Tyrone

John ACTOR, Ardstraw, Co. Tyrone

Roseanna GAMBLE, Strabane

John and Ann FERRIS and children James 9 years, William 7, Jane 4 and Margaret 6 months, Maguiresbridge, Co. Fermanagh

David and Susan WALSH and child Ann 5 years, Maguiresbridge, Co. Fermanagh

Margaret CARR, Maguiresbridge, Co. Fermanagh

Margaret CLUFF, Maguiresbridge, Co. Fermanagh

Henry and Jane MUSGROVE and children Mary 6 years, Catherine 4, Gerrard 2 and Dorothy 6 months, Maguiresbridge, Co. Fermanagh

Margaret BROWN and children Susan 8 years, Margaret 6 and Thomas 2, Maguiresbridge, Co. Fermanagh

Robert BRIEN, Maguiresbridge, Co. Fermanagh

William and Martha MOFFIT and children Andrew 10 years and James 7, Maguiresbridge, Co. Fermanagh

Hugh and Mary CAMPBELL, Newtownstewart

John PARK, Newtownstewart

Luke CONOLY, Newtownstewart

Sarah ADAMS, Newtownstewart

Margaret and Robert PARK, Newtownstewart

Christy and Elizabeth BYEN (?) and children James, Elizabeth 13 years, Mary Ann 12, Christy 6 and Thomas 3, with James ARTHUR 12 and William ARTHUR 9 months, Enniskillen

John and Margaret JOHNSTON, Enniskillen

source for passenger lists PRONI (Public Records Office Northern Ireland) Ref: D2892/1/1

Not less than 15,000 of the children of Erin, flying from famine and landlord tyranny and stricken by fever, lie buried in Grosse Isle.

The following news articles are transcribed by Teena from the Banner of

Ulster, Dublin Evening Mail, Dublin Mercantile Advertiser, Freeman’s

Journal, Northern Whig, and the Tyrone Constitution. (unless otherwise noted)

17 June 1847

Great fears are entertained that sickness will be brought into the provinces by the number of emigrants who are expected to arrive during the summer. To a great degree the fears of the people of this country respecting the arrival of fever with the emigrants have been verified. All the ships which have arrived at the quarantine station at Grosse Isle, below Quebec, have lost a great number by death on the passage out, and the hospital on the island, as well as the ships are crowded with sick. None of them have yet been allowed to come up to the city, but proper medical and other attendance has been sent down to them. (From the Montreal Transcript of May 27)

The number of emigrants who had arrived at Quebec to the 27th May were 5546; To same period last year,5332; 25 sail of emigrant ships are at Grosse Isle. (Caledonian Mercury)

19 Jun 1847

All the ships which arrived at the quarantine station at Grosse Isle, below Quebec, lost a great number by death on the passage out, and the hospital on the island, as well as the ships, are crowded with sick. Accommodation has been provided there for 10,000 persons. Every building on the island that can be spared, including some new sheds, just erected. were crowded with the sick. The dead are tumbled into a hole without coffins or anything else but what they may have on when they die. We have heard of 220 deaths at sea; Seventy on board the vessel, ‘the Cherokee’. Eighteen persons died in one night at the hospital at Grosse Isle. Boards of health have been established, and the most stringent measures of precaution adopted. (Limerick Chronicle)

21 Jun. 1847

Emigration to Quebec

On the 20th ult. Mr. BUCHANAN, agent for emigrants, had advices that 40 vessels had sailed for Quebec, from Waterford, Sligo, Dublin, Londonderry, Belfast, New Ross, Limerick, Cork, Newry, and Liverpool, having on board 12,300 passengers. A large number of emigrants by other ships had reached Quebec, and one vessel, the ‘Exmouth’, from Londonderry, had been shipwrecked.

On the 23rd ult. 1,335 passengers reached Quebec by sea and 12 ships, chiefly from Ireland, with over 4,000 passengers, were at the quarantine ground below, where accommodations have been provided for 10,000 persons. The deaths on board the ships that have arrived are very numerous, Fifty died on board the ‘Agnes’, from Cork, 45 in the ‘Wandsworth’, 10 in the ‘Jane Black’, 20 in the ‘George’. On the 23rd ult. 436 fever patients were in the Grosse Isle hospital, and the probability is that the number will augment daily.

26 June 1847

Reports from the quarantine station at Grosse Isle are unfavourable. There are 1,300 sick, and about 13,000 in 40 vessels at the station. According to all accounts death and starvation are nearly as bad at Grosse Isle as in Ireland. The number of orphans is now about 100.

29 June 1847 Canada Emigration

By the Hibernia, we have received files of Canadian papers to the latest dates. They give appalling accounts of the suffering of the Irish emigrants from fever and dysentery.

The Quebec Gazette of June 9, contains the following – The Marine Hospital is rapidly filling with sick passengers, landed from vessels coming in to port from Grosse Isle. Five deaths occurred on board the steamer ‘Canada’, on her way up to Montreal. A thousand passengers were crammed into this comparatively small boat. Two other members of the French Catholic clergy went down to Grosse lsle on Monday, the Rev. Mr. Hunt, cure of St. Foy, and the Rev. Mr. Brady, vicaire of Kakouna. The Rev. Mr. M’Gauran, has returned from the island, sick with typhus and is now at the General Hospital. A gentleman who visited the island on Saturday last, has given the following statement –

“There were then 21,000 passengers at Grosse lsle, 960 died on the passage out; 700 died at the station; there were 1,500 sick on board the vessels; 1,100 sick on shore; and 90 died on Saturday.”

Bills are stuck up calling for 50 female nurses and 20 orderlies, for the service of the hospitals at Grosse-lsle. Wages, £3 per month, with rations.

Wreck of an Emigrant Vessel Dreadful Loss of Life

The Quebec Gazette of June 11 says; in a letter dated at Cape Rosier May 19th, which appeared in our paper of Monday last, announcing the melancholy fate of the brig “Carricks”, R. THOMPSON master, from Sligo, which was lost near that place with all her passengers except 48, and one boy belonging to her crew, the number of passengers was stated to be 167; so that 119 of them would appear to have perished, and with the boy, in all 120 persons. In looking over a file of Irish papers received by last mail, we have met with an extract from a Sligo paper, according to which the number drowned, including the boy, would be 129, instead of 120, unless the ill-fated ship had already lost 9 of her passengers, before the awful catastrophe, by which, so many of the poor people sent out free by Lord Palmerston, were consigned to a watery grave.

The ‘Miracle’ which left Liverpool towards the end of March, with 400 emirants, was, on the night of the 9th of May, wrecked off the Magdalen Islands and 70 of the emigrants were drowned. The survivors were conveyed to Picton. Twenty of the unfortunate emigrants had previously perished from fever.

Wreck of Four Ships

The ‘Miracle’, Captain ELLIOTT, sailed from the port of Liverpool in the latter part of March last, for Quebec; besides her crew, she had on board no fewer than 400 emigrants. In a gale of wind, on the night of the 9th May, this unfortunate vessel was driven ashore on reef of rocks off the Magdalen Islands, where, in a few hours, she became a complete wreck. The moment she struck, her masts fell overboard and the captain of the ship, seeing that the loss of his ship was inevitable, had the boats lowered and with his crew, exerted all possible means to preserve the lives of the emigrants, who crowded the decks in the greatest state excitement. After incessant zeal, the greater part of the poor creatures were got safely ashore on the island, but in two instances the boats struck against the rock, were shattered to atoms and their living freight, amounting to nearly 70 persons, were drowned. Before the vessel arrived off Magdalen Islands, a fever had broken out among the emigrants, which carried off 20. The names of those who perished are not mentioned in the particulars received at Lloyd’s; survivors are said to have been conveyed to Picton, where they arrived on the 29th. The vessel had been properly surveyed before her sailing from Liverpool; she was strongly built and registered at Lloyd’s as 627 tons, having been built at St. John’s, New Brunswick, in 1841. It is not known if she were insured.

Two English vessels were lost on the same night, 60 miles southward of Magdalen Islands. One was from London to Quebec, called the ‘Brothers’, the property of Messrs. Brooks and Co., of Southwark. All hands, it is supposed, were lost. Letters from Suez, dated June 8, received by overland mail, announce the total loss of the barque, ‘Welcome’, belonging to Greenock, on a coral rock off the Island of Yambo, in the Red Sea. It was attended with melancholy loss of life. The chief mate, an Arab pilot and also 12 of the seamen, drowned. The accident occurred at 12 o’clock in the night of the 14th of Apr., the vessel being on her homeward passage. No sooner did she strike than the vessel turned over on her beam ends, and shortly sank in 70 fathoms of water. Another loss, that of a whaler, off the coast of New Zealand, is also reported at Lloyd’s. It is that of the ‘Delphos’, 500 tons burden,commanded by Captain WEST.

Shipwreck of The “Exmouth” which left Londonderry 25 April 1847 wrecked 28th April 1847; lives lost 251

Yet think this furious unremitting gale

Deprives the ship of every ruling sail;

And if before it she directly flies,

New ills enclose us and new dangers rise.

The western coast of Scotland, like the western coast of Ireland, is jagged with rocks and be-studded with islands. The hoarse Atlantic ocean has beaten upon it during all time, and the cliffs and headlands and rocky groups, evince the sturdy fashion in which the land has stood out against the in-roads of the sea, fighting, so to speak, every inch of ground with the invader. Tourists love the western coast of Scotland for its picturesqueness and its solitary wildness. If you are an admirer of fine coast scenery, I can wish you no greater treat than to sail amongst the charming islands, that are strewed up and down this shore, and to run along sufficiently near the mainland to catch a glimpse of the purple mountains of the Highlands. Considering the dangerous character of this coast, comparatively few wrecks occur; the dangers being well known are avoided with more than usual care, and moreover they do not lie much in the track of seagoing vessels.

In 1847, the poor people of Ireland were eagerly entering into that great emigration movement which has never ceased up to the present moment, and in connection with which so many disastrous shipwrecks have occurred. They bade farewell to the green Erin they loved and turned their faces to the western continent as the Israelites, departing from Egypt, turned their longing eyes to the land of Canaan.

It was Sunday morning April the 25th in the year 1847.

At Londonderry, – ‘the famous Derry of ‘prentice boy history’ – there lay a brig of 320 tons. In that olden time, of which I spoke some time since, they knew more of brigs than we do. Brigs are somehow going out of fashion but a sailor will tell you that handier craft never go to sea; they are splendid seagoing ships and so obedient that they will, as sailors are fond of saying, “turn in their own length”. The ‘Exmouth’ was a full grown specimen of her class. Upon her decks on this spring afternoon 240 emigrants were waiting the moment when the brig would be cast loose to convey them to Canada. There was a crew of eleven men only; there were the 240 emigrants; there were three young ladies on their way to join friends in New Brunswick. The emigrants were of a better class than you generally understand by the term.

Small farmers who had struggled on their bit of land to obtain a competence, and tradesmen anxious to do something more than live a hand to mouth existence, had been told that the good time coming would come quickest in the land across the Atlantic. Good news had been wafted over from friends and relations who had gone before. You can imagine, therefore, how high beat the hearts of these Irish men, women, and children, as amidst the sorrow of the ‘good-bye’ which was at last spoken, they thought of the sunny future.

The Sunday sun had not risen, when up went the sails and the “Exmouth” starting on her voyage, slowly increased the distance between the emigrants and their fatherland. A light south-west breeze bellied out the canvas, and in the afternoon, as the sun was sinking in the direction which the brig was to take, the hills of Old Ireland appeared like a light cloud in the distance and were quite lost sight of before dark. The wind had been gradually freshening, and shifting from the west to the north. It grew at length into a furious gale, and on Sunday night the poor emigrants, instead of their quiet cottages on shore, fragrant with peat smoke, found themselves confined between decks, terror-stricken at the creaking of the ship and the violence of the squalls which made the brig shiver again. On Monday the gale became stronger and the waves, after four-and-twenty hours of tempest, ran frightfully high. The “Exmouth” continually shipped heavy seas; and as each torrent thundered upon the decks, the emigrants in their despair thought their last hour had arrived. In the forenoon the long boat was unshipped and washed away; another sea stove in the bulwarks; and lastly the lifeboat was carried away.

Through the whole of Monday night the gale kept up its violence. and when Tuesday morning dawned it seemed as far as ever from ceasing. The sails were torn to pieces and blown from the ropes. The master of the brig, Captain BOOTH, was on Tuesday night, apprised of a light, of which one of the sailors caught a momentary glimpse when the brig rose to the top of a crest. Unfortunately, for himself, and the lives entrusted to his care, he considered it proceeded from an island on the north-west coast of Ireland. Approaching the light, he himself, became convinced of his error. Instead of the ample sea-room he believed he had, there lay, hard by the rocks of Islay. He was wrong in his reckoning, and fully alive to the perilous position in which his ship was placed, spared no effort to keep clear of the iron-bound shore.

The men flew to the ropes, and set fresh sail, with a view to hauling the brig off. The captain. stationing himself in the maintop. looked anxiously at the land which threatened him; from this post he issued his orders to the crew. Their exertions were, however, too late to be of any use. The brig drifted surely towards land; the broken water soon seethed around her; and about half an hour after midnight of Tuesday, with some of her smaller sails standing, she dashed upon the rocks. Rebounding she returned with her full broadside exposed upon them. Once, twice, and thrice, she again struck. In the last shock the mainmast went by the board, and was carried into a deep chasm of the rocks. While the brig struck, the whole of the seamen rushed into the maintop, where the captain had, for an hour and a half been watching, and his grief was now heightened as he noticed that his son, a lad of fifteen years of age, was not amongst them. The boy had been left in his cot.

Five of the crew thought they might stand a better chance of reaching land by exchanging the main for the foretop, and they put their idea into immediate action. When, therefore, the mainmast fell into the chasm, there went with it the captain and three seamen. These men, first COUTHARD, second LIGHTFORD, and third STEVENS, clung to the spar, and scrambling up the topmast rigging, secured foothold on the crags. The captain and others would have followed had not a returning wave broken upon them, washing them and the ship further into the sea. The mast might otherwise have been made a bridge of safety for the passengers. So vanished the last possibility of escape for the hapless beings who, in the howling of the storm, perished during that night.

No one saw the brig break up; darkness enveloped the work of destruction which the rocks and waves were effectually carrying on. The three seamen who had escaped were the only survivors. They remained shivering in the crevice of the rock till daylight. Not a trace of the “Exmouth” was then visible; the emigrants, one, and all, had perished. At daybreak the three shipwrecked mariners clambered to the summit of the rocks, and with heavy steps sought a farm-house, to tell how of 254 living beings they alone were left to tell the tale of their loss.

I need not add that by the homely, kindly Scotch folks these men were loaded with kindness. A score of bodies were afterwards washed ashore, battered by the rocks almost beyond recognition; these were the remains of some emigrants, who had probably hurried up at the striking of the brig, leaving their companions below. A few bodies were brought in occasionally by the surf, but the sea was too high to admit of their recovery, and they were carried out to be buried in the ocean depths.

Transcribed by Teena from Notable shipwrecks, retold by uncle Hardy By William Senior 1881 https://books.google.ca/

With our Thanks, Maggie Brown has transcribed from the Tyrone Constitution of Friday 14 May 1847 “THE WRECK OF THE “EXMOUTH”

We annex a list of the unfortunate passengers who perished in the above unfortunate vessel, with the numbers in each family and the names of the localities in which they reside, so far as could be ascertained by the agent at Derry, viz:

Ballymoney – Nancy FORGROVE, Patrick McGUEKEN and family, 5 in number; James WYLIE

Ballyshannon – Terence and Patrick MAGUIRE

Clonmany. – John DEVLIN and family 5

Castlederg – Margaret KEALY, 4; Ann GALLAGHER

Dungiven – John McCONNELL, James and Isabella BOYD, James KEALY

Derry – Letty HENDERSON

County Fermanagh – Jane FLANIGAN and family, 8; James CALDWELL, 9; John CRAWFORD, 7

Kilmacreach – Margaret McGETTIGAN and family, 7; Patrick KELLY, 3; John McDERMOTT, 7; William McELHENNY, 2; Edward McGETTIGAN, 6; James BRADLEY, Michael and Margaret McGINLEY, John GALLAGHER

Letterkenny – Brian DOUNELL and family, 5

Na-Limavady – John RIDDLES and family, 2; Matthew MILLER, Sarah MAGILL, 3; James WRIGHT, Jane HARPER and family, 7; David STEEP, 6

Omagh – Ann ALONE. Strabane. – Hugh McCROSSEN and family, 3; John DIZON, 7; Robert BLAIR, 4; Sarah SMITH, Jas. McCREA, 10

Stranorlar – Redmond McCOOL and family, 9

Shenreagh – John WILSON and family, 3

The residence of the subjoined, who were also on board, are unknown to the agent in Derry:

James DIVEN

Owen CURRAN and family 7

Terence HILLY, 7

Patrick WOODS, 6

Bernard McCAFFREY, ?

John COOLAGHAN

James COCHRANE

James DONAGHY

Andrew TEVAIN, 6

Peter COX

Patrick FEE

James, Jane, and Ellen PATTERSON

Patrick LEONARD, 5;

Peter MUEKILHILL, 7

James McGIRR, 3

Denis BROGAN, 11

Total, 206

‘British Whig’, Kingston, Tues. 1 Jun. 1847

Following is a list of the emigrants wrecked and lost in the Brig “Exmouth” from Londonderry to Quebec.

Margaret, Mary and James KELLY

Ann SWEENY

Owen, Sally, John, Nelly, Ann, and Sally CURREN

Thomas GAULAGHER

Redmond, Catherine, Catherine, Harriet, John, Edward, James, Michael and Sally M’COOL

James DIVER

James, Ellen, Bernard, William and John DONNELL

John, Martha, Jane, June (?), William, James and Jane DIXON

Robert, Nancy, Isabella and Ann Jane BLAIR

James and Peggy Jane RIDDLES

Sarah SMITH

James DONAGHY

Edward, Mary, Peggy, Catherine and Daniel M’GETTIGAN

Biddy M’CAFFERTY

Patrick MURRAY

James BRADLY

Michael, Margaret and James M’GIBLEY

James REALY

John Christian and Jane WILSON

Jane, John, Pat, Ann, Rosey, Thos., Jane and Bernard FLANAGHAN

Margt., Nancy, Peggy, Hugh, Mary and John M’GETTIGAN

Pat SINOGH (?)

John, Catherine, Hugh, Peggy, Michael, Rosey and Sally DERMOTT (?)

Ann ALANE (?)

James WRIGHT

Mary, James, Peggy, John, Hannah, George, Samuel and Jane HARPER

George and James CUNNINGHAM

Betty ANDERSON

Mathew MILLER

Pat, James and Gormly KELLY

James, William, Joseph, Moses, Robert, Mary and Jane M’CREA

Andrew, Ann, Rose, Susan, Sarah and James SEVON

Bernard, Billy, Mary and Bernard M’CAFFREY

John M’CONNELL

James and Isabella BOYD

James and Jane PATTERSON

Pat, Catherine, Mary, John and Thomas LENNARD

Ann and John GAULAGHER

Peter COX

Patrick FEE

William and Mary M’ELINRY

John, Margt., Ellen and Richard DEVLIN

Terrence, Bridget and __ HOLLIS (?)

Pat, Catherine, Charles, Mary, William and Ellen WOODS

Hugh, Mary and Catherine M’CROSSAN

Mary FERGUSON

David, Martha, Catherine, Robert, Nancy and John STEEN

James SINGLIE (?)

James COCHRANE

Sarah and James MAGILL

Peter, Ann, Mary, Catherine, James, Anne and John MUCKLEWHITE

John, Anne, George, Robert, Isabella and Maria CRAWFORD

Anne CARROLL

James, Margaret, Mary, James, Jane, Thos., Eliza, Hannah and Margaret COLDWELL

Patrick and Patrick M’GACKEN

Sarah M’KEEN

Hannah and Mary M’GACKEN

William, Margt. and Jane A. SMITH

James, Edwd. and Rachael M’GIRR

Dennis, Biddy, Michael, Peggy, James, John, Dennis, Donald, Biddy and Nelly BROGAN

30 Jun 1847

Wreck of an Emigrant Vessel, Dreadful Loss of Life

the Quebec Gazette of June 11 says – In a letter dated Cape Rosier, May 19th, which appeared in our paper Monday last, announcing the melancholy fate of the brig ‘Carricks’, R. THOMPSON master, from Sligo, which was lost near that place with all her passengers except 48, and one boy belonging her crew, the number of passengers was stated to be 167; so that 119 of them would appear to have perished, and, with the boy, in all 120 persons. In looking over a file of Irish papers received last mail, we have met with an extract from a Sligo paper, according to which the number drowned, including the boy, would be 129, instead of 120, unless the ill-fated ship had already lost some of her passengers before the awful catastrophe by which so many of the poor people sent out free by Lord Palmerston were consigned to a watery grave.

The Miracle, which left Liverpool towards the end of March, with 400 emigrants, was, the night of the 9th of May, wrecked off the Magdalen Islands, and 70 of the emigrants were drowned. The survivors were conveyed to Picton. Twenty of the unfortunate emigrants had previously perished from fever. (Kings County Chronicle)

30 June 1847

The chief topic of conversation at that city, (Montreal Canada) was the sickness at Grosse Island. The latest accounts from that place state that the number of ships still there was about thirty. The number of deaths for the week ending June 8, was 110. It was reported that 120 burials had taken place in Grosse Isle on the 9th Jun.

A letter from our correspondent at Mirimachi states that the ship ‘Loosthank’, Captain Thorn, bound from Liverpool to Quebec, with 350 passengers, out 49 days, put in there in distress, 117 passengers having died on the passage and the crew not able to work the ship. She was to proceed on her voyage as soon as the crew recovered. (The Evening Chronicle)

extract from the Grosse Isle Tragedy pub. 1909

Fever on Board! – the crew sullen or brutal from very desperation, or paralyzed with terror of the plague, the miserable passengers unable to help themselves, or to afford the least relief to each other; ¼, or ⅓, or ½, of the entire number in different stages of the disease, many dying, some dead; the fatal poison intensified by the indescribable foulness of the air breathed and rebreathed by the gasping sufferers the wails of children, the ravings of the delirious, the cries and groans of those in mortal agony. Of the 84 emigrant ships that anchored at Grosse Isle in the summer of 1847, there was not a single one to which this description might not rightly apply.

“The authorities were taken by surprise, owing to the sudden arrival of this plague-smitten fleet and save the sheds that remained since 1832, there was no accommodation of any kind on the island. These sheds were rapidly filled with the miserable people, the sick and the dying. Hundreds were literally flung on the beach, left amid the mud and the stones, to crawl on the dry land how they could. “I have seen,” says the priest who was then chaplain of the quarantine, and who had been but one year on the mission, “I have one day seen 37 people lying on the beach, crawling in the mud and dying, like fish out of water. “Many of these and many more besides, gasped out their last breath on that fatal shore, not able to drag themselves from the slime in which they lay. Death was doing its work everywhere in the sheds, around the sheds, where the victims lay in hundreds under the canopy of heaven, and in the poisonous holds of the plague-ships, all of which were declared to be and treated as, hospitals. Amidst shrieks, and groans, and wild ravings, and heart-rending lamentations, our prostrate sufferers in every stage of the sickness, from loathsome berth, to loathsome berth, he pursued his holy task. So noxious was the pent-up atmosphere of these floating pest houses, that he had frequently to rush on deck to breathe the pure air.

There being, at first, no organization, no staff, no available resources, it may be imagined why the mortality rose to a prodigious rate and how at one time as many as 150 bodies, most of them in a half naked state, would be piled up in the dead-house awaiting such sepulture as a huge pit could afford. Poor creatures would crawl out of the sheds, and, being too exhausted to return, would be found lying in the open air, not a few of them rigid in death. When the authorities were enabled to erect sheds sufficient for the reception of the sick and provide a staff of physicians and nurses, and the Archbishop of Quebec had appointed a number of priests, who took the hospital duty in turn, there was, of course, more order and regularity, but the mortality was for a time scarcely diminished. The deaths were as many as 100, and 150, and even 200 a day, and thus for a considerable period during the summer.

Upon that barren isle as many as 10,000 of the Irish race were consigned to the grave pit. By some the estimate is made much higher and 12,000 is considered nearer the actual number. A register was kept and is still in existence, but it does not commence earlier than June 16, when the mortality was nearly at its height. According to this death-roll, there were buried, between the 16th and 30th of June, 487 Irish immigrants “whose names could not be ascertained.” In July, 941 were thrown into nameless graves and in August, 918 were entered in the register under the comprehensive description “unknown.” There were interred from the 16th June to the closing of the quarantine for that year, 2,905 of a Christian people whose names could not be discovered amidst the confusion and carnage of that fatal summer. In the following year, (1848) 2,000 additional victims were entered in the same register without name or trace of any kind, to tell who they were, or whence they came. Thus 5,000 out of the total number of victims were simply described as “unknown.”

13 Aug. 1847

The Montreal Board of health made a report on the 5th instant, the following paragraphs of which more than corroborate the melancholy statements of the Pilot. Dr. M’CULLOUGH reported that he had this day visited the immigrant sheds and hospitals and found the sick too much crowded, in a manner calculated to prevent their recovery and endanger the lives of all necessary attendants. He found in one apartment, of little more than twenty feet square, 33 women dangerously ill of fever. In the extremity another building, about 20 feet by 50 feet, he found 350 children, including many infants but a few months old, suffering and dying, he regretted to say, for want of food and clothing. He also reported that mortality is increasing in the immigrant hospitals, no less than 54 having died there in the 24 hours ending Sunday afterwards, and that more accommodation in hospital room was imperatively required for the safety of the unfortunate people who are found there. The mortality in the present hospitals is now frightful, owing in a great measure, to the crowding of inmates, which creates a pestilential atmosphere that sickens and drives away physicians and nurses and consequently leaves the weary and helpless sick to die in all the horrors of torment and neglect. Every day makes matters worse. The latest accounts are still more afflicting. On the 13th instant, a fleet of passenger ships arrived at Grosse Isle and here is the terrible record of their condition;

‘Goliath’ from Liverpool; 600 passengers; 46 deaths;

‘Jordine’ from Liverpool; 353 passengers; 8 deaths;

‘Manchester’ from Liverpool; 512 passengers; 11 deaths;

‘Erin’s Queen’ from Liverpool; 517 passengers; 50 deaths;

‘Sarah’ from Liverpool; 248 passengers; 31 deaths;

‘Triton’ from Liverpool; 488 passengers; 90 deaths;

‘Thistle’ from Liverpool; 389 passengers; 8 deaths;

‘Avon’ of Cork; 550 passengers; 136 deaths;

In many these ill-fated ships the survivors were, but just alive. Most of the crew of the ‘Triton’, and half the passengers, were down with the fever and had at once to be removed to the hospitals The ‘Avon’, of Cork was still worse – a real plague ship. date. Up to the 30th June the total number of deaths at Grosse Isle, was 821; on board ships and buried on the island to July 8th, 715; died sea, 2,559; total deaths 4,095. (Cork Examiner)

18 August 1847 The Ship Fever in Canada Quebec, July 24

The fever amongst the emigrants is still raging as destructively as ever. Some diminution has occurred in the number of deaths within the last week, because ships are now beginning to come in more slowly, but the relative proportion is quite great, while the disease has assumed, in many cases, the more dangerous and fatal form of congestion of the brain and lungs.

The quarantine hospitals at Grosse Isle still contain their two thousand patients, while all the available accommodation for the sick in the town itself has been for some days filled up. Most fortunately for the inhabitants of Quebec, comparatively few of the emigrants land amongst them; they are almost entirely embarked direct on board the steamer for Montreal, the healthy from their ships and the so called convalescent from Grosse Isle and are carried away once, without any communication with Quebec, consequently, whilst the disease is daily being conveyed to the Upper St. Lawrence and spread into the western districts, it is here almost solely confined to those whose duties compel their personal attendance upon the sick. Several clergymen and doctors have died and others are dangerously ill, but the fever is decidedly not general in the town, because being contagious only by actual contact with the infected, comparatively few persons are exposed to its poison. Still there is necessarily a strong and constant visible evidence of its neighbourhood; many families are in mourning, a general tone of dullness prevails, scarcely any of the hundreds of travelling Americans who come up each summer have ventured into Canada this year, while the local papers are full of details of the misery and death which is so near.

Last Sunday the Bishop himself performed the entire cathedral service alone, an occurrence probably without parallel and he prefaced an extempore sermon, by stating that with the intense labour he had to undergo and the weekly increasing church duty consequent upon the diminishing number of the clergy, he had been unable to find time to write. Little else is talked about but fever and the strongest possible dissatisfaction prevails universally, first, with the home mismanagement which could allow the possibility of so frightful a result of emigration and secondly, with the complete insufficiency of the quarantine system here for the protection of the country. There is reason enough, indeed, for both complaints.

The first fever ship arrived about the 8th of May. From that time to the present, daily and hourly, arrivals have taken place, and of those who left their cottages this spring, to seek a new and happier home on this side of the Atlantic, one-eighth have but wandered to their graves. About 57,000 persons have arrived in the St. Lawrence up to yesterday and the deaths from typhus now very nearly amount to 7,000.

The list on the 22nd instant stood as follows;

Died at sea 2,216

Died after arrival, but before landing 1,011

Died at Grosse Isle (this only extends to the 16th) 1,201

Died in the Marine Hospital in Quebec 150

Died at Montreal 1,400

Died at various places in the provinces, about 800

Though it might fairly have been expected that in the gigantic amount of Irish emigration intended to take place this year, much increased average of sickness would occur, especially as typhus was very prevalent in all the shipping ports in Great Britain, it appears that no arrangements whatever were made to prepare for it The quarantine station was left in all its practical uselessness; one surgeon and a few sheds constituted its whole establishment and Grosse Isle was “kept up as a rather comfortable farm for the superintending surgeon, than as a sanitory gateway of England’s most valued colony.”

The dead, the dying, and the sick arrived; the buildings on the island, mere outhouses at the best, were rapidly filled, and then the luckless wretches for whom no room could be found to die under roof, were laid on the grass in tents, with the rotten beds they had brought from home; 400 are thus provided for, and as for some days past much heavy rain has fallen, their present state must be one of the most fearful misery. There are but 8 surgeons to attend 2,000 patients, and it is said that many of them do not possess the qualifications which so responsible a position, requires. The convalescent, so called at least, are rapidly sent on to Montreal, but as they die there at the rate of nearly 30 percent and carry fever wherever they go, it is fair to suppose that many, if not all of them, are got rid of much too soon, and rather to make room for others, than because they are recovered themselves. In one steamer, which carried up a party of “convalescents” from Grosse Isle to Montreal, 17 died, though the passage did not occupy 20 hours.

Strange to say, there is regular communication between Quebec and the quarantine station. Most people labour under the impression that such a place is shut off from the rest of the world with the ‘cordon sanitaire’ preserved in all its strictness around it; but here there is generous disregard of such precautions, and an Irishman may go down to the hospital sheds, bring away the ragged, filthy garments of his dead wife, and carry them in a bundle pestilent with fever, through the streets and into the houses of Quebec. This has been actually done in several cases. Of course, sickness must result from such proceedings, but there are wardens constantly occupied in the lower town removing the infected, doing all they can to counteract the effects of the poison by enforcing cleanliness and other similar precautions.

The sufferers are, without exception, Irish, amongst the English emigrants scarcely a case of fever has occurred, while the Liverpool and Cork vessels have had it worst. In many cases the fever broke out before the ships had been a week at sea; in others, it is mainly attributable to the infamous negligence of the masters and mates, who frequently have never, during the whole of the voyage, once gone below, but have left their passengers to rot in dirt and foul air, without attempting, in the slightest degree, to make them clean their berths or persons. In some of these ships the boarding officer at Grosse Isle has actually had to lay down planks over the liquid filth and dirt, which covered up the ’tween decks, to the depth of many inches, before he could force his way to the beds in which the unhappy passengers were dying. The food provided has sometimes been so bad, that the flour has produced ulcers on the inside of the lips and mouth, while the salt beef and pork has been thrown overboard as utterly poisonous. Many vessels left Ireland and England with typhus fever evident amongst the people before they sailed; the master of the ‘Pursuit’ from Liverpool, has signed a declaration that he took many passengers on board with fever, and that he objected to them, and that 2 deaths occurred before he left the dock. The master the ‘Helen’ of Sligo, certified that he sent ashore a family who had been embarked sick; that they were re-shipped by the agent, that 2 of them died a few days after sailing, and that the whole ship was infected by them. With such cases as these before them, the Canadians have some reason to complain. They ask, what are the duties of the government emigration agents at the British ports, but to examine ships, provisions and passengers before they sail, and to secure the latter, as far as men can, against the risk of such frightful consequences? To say that these agents do their duty with the utmost energy and activity is most probably true enough, but how can one man in the widest scope of possibility really perform such a duty, as it requires. The government agent at Liverpool is said to be one of the most overworked men in England, as well one of the most industrious and energetic, but what can he do with half a dozen ships a day sailing with 400 passengers in each? Emigration will increase, it has increased enormously, and yet this year some of the members of the House of Commons objected to the grant for the support of the emigration commission, and its staff of agents. Were there three times as many they would all be well occupied, and certainly the inhabitants of the colonies, as well as the poor emigrants themselves, have a right to expect that their interests and comforts, to say nothing of their safety, shall be carefully watched over and provided for. That the horrible amount of death and suffering attendant upon this year’s emigration might to a great extent have been prevented by proper care and rigid examination at home, no one can attempt to deny, and it is the duty of government to enable the emigration commissioners to render the supervision for the next year so complete that the prospect of a similar result shall be destroyed.

On the arrival of ships at Grosse Isle, if they are found to have no epidemic or infectious disease on board, they are allowed to proceed direct to Quebec, and it is of passengers from such vessels the majority of the wanderers in the streets here are composed. They present generally a most wretched appearance, but demand the most ridiculously high wages, and many of them remain idle for a fortnight, rather than accept a lower rate than 6 shillings a day, while the regular pay for strong and experienced labourers does not exceed three. It is a curious fact, and one utterly inexplicable here, that on the dead bodies of many of the most miserable looking Irish sums of money, varying from 5£ to 50£ have been found concealed in their clothes; and yet these very men allowed themselves and their families to actually expire from want of food.

The report of the provincial emigrant agents speak encouragingly of demand for labour, but the fear of introducing fever amongst themselves will prevent many employers from engaging this year’s emigrants. Still, all who can and will work are rapidly absorbed and the chief emigrant agent at this port, whose position is now one of the utmost difficulty and labour, forwards the destitute, as far as the funds at his disposal will allow, on to the districts where they will most probably meet with employment; but the drain upon his treasury for hospitals and burials, and every expense contingent upon universal sickness and universal death, leave him but a small sum, comparatively, to apply to the more regular and legitimate expenditure. It is impossible to announce any expected termination to the fever; no remedies can stop it and it will only end when it has worn itself out.

30 Aug. 1847

The intelligence of the emigrants to Canada received per the Hibernia is very distressing in every respect. The numbers have been great, and the survivors of fever are likely to suffer the utmost privations from want of employment during the ensuing winter. The Gazetter of the 11th August, says – “The prospects of the immigrants who may survive till the winter is still more alarming than their present condition. They have left their country. like the forefathers of all the European descendants who now inhabit America, in the hope of bettering their condition. Under present circumstances they are likely to be worse off than at home. The common feelings of humanity and religion obligation require every one to succour them as much as his means will permit and be thankful that their own lot has not been so unfortunate”. So the emigrants have only passed from bad to worse. Their number to Canada is nearly 80,000 and nearly half a million pounds must have been paid to remove them from charity at home, to beggary in the colonies; although a similar sum judiciously expended in their own country would have given to them permanent employment, while a good return would have been annually derived from the outlay. “The deaths at the Marine Hospital and the adjacent sheds are about a hundred a week out of about a thousand patients. At the quarantine stations the deaths have increased. The fever is spread generally to those parts of the country where the unfortunate emigrants have proceeded; but as yet, it has been chiefly confined to them.”

The Quebec Morning Chronicle affords the following state of the condition of Grosse Island 7th August – “We received this morning the subjoined intelligence from Grosse Isle, reaching to yesterday, from which it will be seen that for the week ending 7th instant, there were 307 deaths in all, at the hospital, the tents, and on board the vessels at the session.

There are 2,038 cases of fever, and 78 of small pox. There were 24 deaths at the tents allotted for the healthy passengers, during the name period. The bodies of 40 adults and 47 children have been landed from the vessels there and buried on the island. The passengers of the ‘Free Trader’, ‘Saguenay’, ‘Larch’ and ‘Ganges’ had not been landed for want of room on the island.

Remaining in Hospital yesterday Aug. 10th; 856 Men; 726 women; 518 children.

This statement extends only to one portion of the hospital accommodation, and does not include that return which we have quoted from the Quebec. Gazette. Neither of them includes the Montreal deaths. We must turn to another paper for that list and although the Montreal Herald does not give full or late particulars, yet as it has the only information presently in our hand, we copy from its number of 13th August – “The condition of the emigrants daily arriving amongst us, though somewhat less painful than at the commencement of the season, is still most distressing. The whole number landed during the season to the 15th of August, in Quebec and Montreal, was 70,006, being 42,863 more than last year. Of these, 4,572 had died at Grosse Isle up to the 4th July; and on the 6th August, there were 2,148 sick in the hospital there. In Montreal at this date, there are in the Emigrant hospital 1,179 sick prisons and during the past fortnight, the deaths at the sheds have amounted to 286. But this does not exhibit the whole loss of life; for, besides several deaths reported by the usual municipal authorities, it appears that 386 persons have been buried in the emigrant burial ground since the 29th June, whose deaths have not been reported at all. We can, therefore, hardly put the numbers down at less than 450 persons in the fortnight. Still these extracts do not bring up the deaths in other parts of the province. We are only informed that fever has extended to other quarters and has principally attacked the emigrants. They also necessarily omit the numbers who perished on the voyage and were buried in the Atlantic. They, of course, take no account of those who were otherwise lost on the passage, but the numbers of the drowned is very considerable.

The Quebec Gazette gives us the following summary of those stricken by fever, who have sunk beneath the blow. “Including the mortality on board the ships on the passage, at Montreal and in Upper Canada, the deaths, out of nearly 80,000 passengers, are probably an eigth of the whole.”

The Mail has been accused most virulently of offering an unreasonable opposition to emigration during this season; but we rejoice that, neither directly, nor indirectly, do we have the slightest responsibility for the course which has caused the death of these ten thousand persons, who might all have been profitably employed in the parishes, or in the country, from which they were sent forth to die. (North British Daily Mail)

7 Sept. 1847 The ship Fever in Canada, Kingston, Canada West, Aug. 10th